====================

This address was given on Sunday, January 27, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector. The day was celebrated as the Patronal Feast of the parish by translating the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul from January 25 to this, the closest following Sunday. Rather than preach on the propers of the day (Epiphany 3) or of the translated feast, Fr. Funston offered this assessment of the parish and how well it meets the vision of The Dream, a prophetic piece of prose written more than thirty years ago by the late Wesley Frensdorff, one-time bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada.

(Lessons for the Conversion of St. Paul according to the practice of the Episcopal Church: Acts 26:9-21; Psalm 67; Galatians 1:11-24; and Matthew 10:16-22. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

More than thirty years ago, a bishop named Wesley Frensdorff set out his vision for the church in a piece of writing he title simply The Dream. Wes Frensdorff was a good friend to Evelyn and to me. He was her parish priest when she was a child, and her boss when she was the director of the Diocese of Nevada’s summer camp. He officiated at our wedding, and is the person who spoke for God and hounded me into eventually becoming a clergyman. As my Rector’s Report, I’d like to share his dream with you, adding my own brief comments as to how I see this church meeting his vision.

More than thirty years ago, a bishop named Wesley Frensdorff set out his vision for the church in a piece of writing he title simply The Dream. Wes Frensdorff was a good friend to Evelyn and to me. He was her parish priest when she was a child, and her boss when she was the director of the Diocese of Nevada’s summer camp. He officiated at our wedding, and is the person who spoke for God and hounded me into eventually becoming a clergyman. As my Rector’s Report, I’d like to share his dream with you, adding my own brief comments as to how I see this church meeting his vision.

Bishop Frensdorff begins . . .

Let us dream of a church . . .

in which all members know surely and simply God’s great love, and each is certain that in the divine heart we are all known by name.

in which Jesus is very Word, our window into the Father’s heart; the sign of God’s hope and his design for all humankind.

in which the Spirit is not a party symbol, but wind and fire in everyone; gracing the church with a kaleidoscope of gifts and constant renewal for all.

I think that is the sort of church we at St. Paul’s Parish are, a congregation which knows God and God’s Son and in which everyone’s gifts and ministries are welcomed, empowered, and celebrated. We have just received written and oral reports on the many and varied ways in which those gifts and ministries are embodied in our parish.

The bishop continues . . .

A church in which . . .

worship is lively and fun as well as reverent and holy; and we might be moved to dance and laugh; to be solemn, cry or beat the breast.

people know how to pray and enjoy it – frequently and regularly, privately and corporately, in silence and in word and song.

the Eucharist is the center of life and servanthood the center of mission: the servant Lord truly known in the breaking of the bread, with service flowing from worship, and everyone understanding why worship is called a service.

I believe we are such a congregation. We have affirmed often that we are a Eucharisticly-centered parish, a prayerful people, and a place of service. We have an active parish prayer chain; we have groups which meet weekly to read spiritual writings or study the Holy Scriptures (and I wish there were more of those); we have just instituted a new chapter of the Order of the Daughters of the King, whose ministry is one of intentional prayer. This is a parish with an active corporate and individual prayer life.

Let us dream of a church . . .

in which the sacraments, free from captivity by a professional elite, are available in every congregation regardless of size, culture, location, or budget.

in which every congregation is free to call forth from its midst priests and deacons, sure in the knowledge that training and support services are available to back them up.

in which the Word is sacrament too, as dynamically present as bread and wine; members, not dependent on professionals, know what’s what and who’s who in the Bible, and all sheep share in the shepherding.

in which discipline is a means not to self-justification but to discipleship, and law is known to be a good servant but a poor master.

I believe we are or are becoming such a congregation. We are a parish in which leadership of worship is shared, in which many study the Holy Scriptures (though I wish more would do so), and in which the discipline of the Christian life is a matter of trust and grace. This is a parish in which the “sheep share in the shepherding;” in addition to our Lay Eucharistic Visitors, we have many in our congregation who’s personal ministry is keeping in touch with those they may not see in church, those whom they know to be in need of a friendly visit, those who may not speak up when they are lonely. It is a delight to be the priest in a place where many share the pastoral service which is the ministry of the priesthood of all believers.

A church . . .

affirming life over death as much as life after death, unafraid of change, able to recognize God’s hand in the revolutions, affirming the beauty of diversity, abhorring the imprisonment of uniformity, as concerned about love in all relationships as it is about chastity, and affirming the personal in all expressions of sexuality;

denying the separation between secular and sacred, world and church, since it is the world Christ came to and died for.

I believe we are such a congregation. We are a parish which welcomes all regardless of race, origin, or sexuality; we are a parish in a tradition which boldly proclaims that creation is good and which seeks to husband and enhance that goodness.

A church . . .

without the answers, but asking the right questions; holding law and grace, freedom and authority, faith and works together in tension, by the Holy Spirit, pointing to the glorious mystery who is God.

so deeply rooted in gospel and tradition that, like a living tree, it can swing in the wind and continually surprise us with new blossoms.

I believe we are such a congregation. St. Paul’s Parish is a household which welcomes the seeker, the questioner, the curious, and the new, offering not easy, black-and-white answers, but responses and exploration in a community of questioners.

Let us dream of a church . . .

with a radically renewed concept and practice of ministry, and a primitive understanding of the ordained offices.

where there is no clerical status and no classes of Christians, but all together know themselves to be part of the laos – the holy people of God.

a ministering community rather than a community gathered around a minister.

where ordained people, professional or not, employed or not, are present for the sake of ordering and signing the church’s life and mission, not as signs of authority or dependency, nor of spiritual or intellectual superiority, but with Pauline patterns of “ministry supporting church” instead of the common pattern of “church supporting ministry.”

where bishops are signs and animators of the church’s unity, catholicity, and apostolic mission, priests are signs and animators of her Eucharistic life and the sacramental presence of her Great High Priest, and deacons are signs and animators – living reminders – of the church’s servanthood as the body of Christ who came as, and is, the servant slave of all God’s beloved children.

I hope we are becoming such a congregation in such a diocese. We have affirmed and celebrated today the ministry of many of God’s people through the activities and outreach of this parish. I look forward to a time when there may be one or more additional priests to animate (as Bishop Frensdorff put it) our Eucharistic life, when there may be one or more deacons to animate our life of service and servanthood, but whether we have those or not, we are now a community which, nourished on Christ’s Body and Blood, is corporately and individually reaching out in service to our community. The Free Farmers’ Market is our largest and most active corporate outreach ministry; but we have many members who are active in public service as hospital and hospice volunteers, as board members of charities, as tutors, and in a variety of other ways. Their public service is a testament to the Christian witness of this church to which they belong.

Let us dream of a church . . .

so salty and so yeasty that it really would be missed if no longer around; where there is wild sowing of seeds and much rejoicing when they take root, but little concern for success, comparative statistics, growth or even survival.

a church so evangelical that its worship, its quality of caring, its eagerness to reach out to those in need cannot be contained.

I believe we are becoming such a congregation. At a recent meeting of leadership in this parish, one of our people said, “I’m looking forward to failing!” What he meant was that he looks forward to us going out into the community around us with (as the bishop says) “little concern for success,” simply going out and getting something done, spreading the Gospel without worrying about the final outcome, which is always and ever in God’s hands.

A church . . .

in which every congregation is in a process of becoming free – autonomous – self-reliant – interdependent, none has special status: the distinction between parish and mission gone.

where each congregation is in mission and each Christian, gifted for ministry; a crew on a freighter, not passengers on a luxury liner.

of peacemakers and healers abhorring violence in all forms (maybe even football), as concerned with societal healing as with individual healing; with justice as with freedom, prophetically confronting the root causes of social, political, and economic ills.

which is a community: an open, caring, sharing household of faith where all find embrace, acceptance. and affirmation.

a community: under judgment, seeking to live with its own proclamation, therefore, truly loving what the Lord commands and desiring his promise.

I believe this is what we meant when we declared, as a congregation, that St. Paul’s Parish’s reason for being is “to set hearts on fire for Jesus” and that our mission is “to advance the Kingdom of God through liturgical worship, spiritual education, personal growth, and service to others.”

And finally, let us dream of a people

called to recognize all the absurdities in ourselves and in one another, including the absurdity that is Love,

serious about the call and the mission but not, very much, about ourselves,

who, in the company of our Clown Redeemer can dance and sing and laugh and cry in worship, in ministry, and even in conflict.

[Frensdorff was a great lover of clowns who often used the clown as a metaphor or illustration in his preaching about Jesus.]

I recently read an essay entitled Why Does God Need the Church? by Ragan Sutterfield, an Episcopalian who lives in Arkansas. Sutterfield’s answer is that God needs the church “to be God’s real presence in the world . . . a radical and amazing call for a group of people.” But, he wrote, “we need to realize . . . that the buildings, the ecclesial bodies, the liturgies, the hierarchies, the bishops, the priests, the laity, the budgets, etc, etc, etc, are only valuable as parts of the church in so far as they are fulfilling the mission of God. And . . . God’s mission is not nice services for nice people in nice buildings.” (Emphasis added.)

Sutterfield, I think, is echoing Bishop Frensdorff’s vision. In doing so, Sutterfield, proposed two new ways to think of our church congregations. First, as “icon” – an icon, he says, is an image that sparks the imagination to move beyond the image and see God. The question we must ask ourselves is “Are we such a community? Looking at us, visiting us, worshiping with us, being served by us, and serving with us, are others moved beyond us to see God?” I believe that we are such a community and I hope that others see through us in that way.

Sutterfield’s second new image of the church is as a “dojo.” A dojo, as you probably know, is “a practice community within martial arts – it is the place where adherents to a specific form come together to learn how to be better practitioners, both from each other and from recognized masters of the form.” It is, simply put, the place and community where people come to get better at what they do. In the church-as-dojo, the congregation becomes the place where we come together to work at becoming more Christ-like. The church becomes a place where we come not to sing some nice songs and hear an occasionally good sermon, but a community with which we gather to explore the faith with one another, recognizing that some among us are more practiced than we may be, challenging each other and learning from one another how better to practice the way of Jesus.

Sutterfield concludes with a vision not too much different from Bishop Frensdorff’s:

Imagine a church where, after a few months of regularly attending, you are able to recognize that you are less angry than you used to be. Imagine a church that shows you how to forgive the person who hurt you most profoundly. Imagine a church that measures your love of God as Dorothy Day did hers, by how much you love the person you love least. Imagine a church that loves you for who you are, away from all of the facades of the self, and teaches you how to love.

I believe that St. Paul’s Parish is and is constantly becoming such a place and such a community. The reports we have received today, the leadership our vestry and officers provide, the ministries of all of our members, all demonstrate that that is so, and for that I am grateful to each of you and to God.

Let us pray:

Almighty and everliving God,

ruler of all things in heaven and earth,

hear our prayers for this parish family.

Strengthen the faithful, arouse the careless, and restore the penitent.

Grant us all things necessary for our common life,

and bring us all to be of one heart and mind

within your holy Church;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Will you turn to the prayers page of the Annual Journal and join me in the “Disturb us, Lord” prayer attributed to Sir Francis Drake which our Inviting the Future Committee adopted as the guiding prayer for our capital project. After the prayer, we’ll sing I Have Decided to Follow Jesus (which is on the back cover of the Journal) and stand adjourned.

Disturb us, Lord, when we are too well pleased with ourselves, when our dreams have come true because we have dreamed too little, when we arrived safely because we have sailed too close to the shore.

Disturb us, Lord, when, with the abundance of things we possess, we have lost our thirst for the waters of life. Having fallen in love with life, we have ceased to dream of eternity and in our efforts to build a new earth, we have allowed our vision of the new Heaven to dim.

Disturb us, Lord, to dare more boldly, to venture on wider seas where storms will show your mastery; where losing sight of land, we shall find the stars.

We ask you to push back the horizons of our hopes; and to push us into the future in strength, courage, hope, and love. Amen.

“The tongue of a teacher” is a such a ripe and fruitful image — it calls to mind all those wonderful people who are so formative in our lives. I remember particular teachers from throughout my life who have been and still are forces that formed and form who I am.

“The tongue of a teacher” is a such a ripe and fruitful image — it calls to mind all those wonderful people who are so formative in our lives. I remember particular teachers from throughout my life who have been and still are forces that formed and form who I am. I confess to a certain fondness for the Galatians. I’ve never been a really big fan of Paul the Apostle and I sometimes wistfully wonder how our Christian faith might have developed if he had not been its principal post-Ascension spokesperson. What if the Johanine community that produced the Gospel of John and the three letters that also bear his name had been more prominent? What if James and his insistence on works of mercy because “faith, if it has no works, is dead” (James 2:17) had been more influential than Paul’s assertion to the Romans that salvation is “by grace, it is no longer on the basis of works” (Romans 11:6)? Well, we’ll never know . . . but apparently the Galatians were listening to someone suggest an alternative to Paul’s understanding of the Christian gospel and, as a result, he wrote them this letter. Anybody that could so upset Paul that he would call them “you foolish Galatians” (Gal. 3:1) gets high marks in my book! That the Galatians were also Celts with whom I, as an Irish-American, share an ethnic heritage gives them additional credit.

I confess to a certain fondness for the Galatians. I’ve never been a really big fan of Paul the Apostle and I sometimes wistfully wonder how our Christian faith might have developed if he had not been its principal post-Ascension spokesperson. What if the Johanine community that produced the Gospel of John and the three letters that also bear his name had been more prominent? What if James and his insistence on works of mercy because “faith, if it has no works, is dead” (James 2:17) had been more influential than Paul’s assertion to the Romans that salvation is “by grace, it is no longer on the basis of works” (Romans 11:6)? Well, we’ll never know . . . but apparently the Galatians were listening to someone suggest an alternative to Paul’s understanding of the Christian gospel and, as a result, he wrote them this letter. Anybody that could so upset Paul that he would call them “you foolish Galatians” (Gal. 3:1) gets high marks in my book! That the Galatians were also Celts with whom I, as an Irish-American, share an ethnic heritage gives them additional credit. More than thirty years ago, a bishop named Wesley Frensdorff set out his vision for the church in a piece of writing he title simply The Dream. Wes Frensdorff was a good friend to Evelyn and to me. He was her parish priest when she was a child, and her boss when she was the director of the Diocese of Nevada’s summer camp. He officiated at our wedding, and is the person who spoke for God and hounded me into eventually becoming a clergyman. As my Rector’s Report, I’d like to share his dream with you, adding my own brief comments as to how I see this church meeting his vision.

More than thirty years ago, a bishop named Wesley Frensdorff set out his vision for the church in a piece of writing he title simply The Dream. Wes Frensdorff was a good friend to Evelyn and to me. He was her parish priest when she was a child, and her boss when she was the director of the Diocese of Nevada’s summer camp. He officiated at our wedding, and is the person who spoke for God and hounded me into eventually becoming a clergyman. As my Rector’s Report, I’d like to share his dream with you, adding my own brief comments as to how I see this church meeting his vision. As anyone who knows me will testify, I am no Calvinist! But hats off to John Calvin who wrote about these verses, “God has manifested himself to be both Father and Mother so that we might be more aware of God’s constant presence and willingness to assist us.” (Commentaries, Vol. 8, Baker Books:2005) Isaiah’s words on behalf of God are among the strongest maternal images of God in Holy Scripture. Just three chapters later, speaking through the prophet, God will ask and declare, “Can a woman forget her nursing child And have no compassion on the son of her womb ? Even these may forget, but I will not forget you.” (49:14-15) And, again, Calvin wrote, “God did not satisfy himself with proposing the example of a father, but in order to express his very strong affection, he chose to liken himself to a mother, and calls His people not merely children, but the fruit of the womb, towards which there is usually a warmer affection.”

As anyone who knows me will testify, I am no Calvinist! But hats off to John Calvin who wrote about these verses, “God has manifested himself to be both Father and Mother so that we might be more aware of God’s constant presence and willingness to assist us.” (Commentaries, Vol. 8, Baker Books:2005) Isaiah’s words on behalf of God are among the strongest maternal images of God in Holy Scripture. Just three chapters later, speaking through the prophet, God will ask and declare, “Can a woman forget her nursing child And have no compassion on the son of her womb ? Even these may forget, but I will not forget you.” (49:14-15) And, again, Calvin wrote, “God did not satisfy himself with proposing the example of a father, but in order to express his very strong affection, he chose to liken himself to a mother, and calls His people not merely children, but the fruit of the womb, towards which there is usually a warmer affection.” So let’s admit right off the bat that we have a problem here. Where the progressives and liberals among us would much prefer to read Paul condemning the institution of slavery, he does not. Instead, he simply admonishes slaves to be good slaves and masters to be good masters, and even goes so far as to analogize a Christian’s relationship with God (or Jesus) to slavery. This just doesn’t sit well in the modern mind and provides plenty of ammunition for those whom Friedrich Schleiermacher addressed as religion’s “cultured despisers.” We would much rather Paul hadn’t said this.

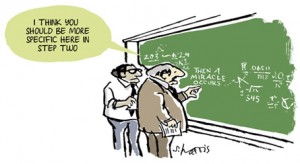

So let’s admit right off the bat that we have a problem here. Where the progressives and liberals among us would much prefer to read Paul condemning the institution of slavery, he does not. Instead, he simply admonishes slaves to be good slaves and masters to be good masters, and even goes so far as to analogize a Christian’s relationship with God (or Jesus) to slavery. This just doesn’t sit well in the modern mind and provides plenty of ammunition for those whom Friedrich Schleiermacher addressed as religion’s “cultured despisers.” We would much rather Paul hadn’t said this. My late brother had a cartoon cut from some magazine taped to the door of his university office (he was a professor of political science and constitutional law) for years. I suspect it came from either Playboy or The New Yorker, but I really don’t know. It depicted two scientists working at a chalk board. To their left on the board was a complicated looking mathematical formula and to their right, another one. Connecting the two sets of numbers were arrows drawn from and to the words, “The a miracle occurs.” One of the scientists speaking to the other says, “I think you should be more specific here in step two.” (Of course, I’ve been able to find the cartoon on the internet and will post it with this meditation.)

My late brother had a cartoon cut from some magazine taped to the door of his university office (he was a professor of political science and constitutional law) for years. I suspect it came from either Playboy or The New Yorker, but I really don’t know. It depicted two scientists working at a chalk board. To their left on the board was a complicated looking mathematical formula and to their right, another one. Connecting the two sets of numbers were arrows drawn from and to the words, “The a miracle occurs.” One of the scientists speaking to the other says, “I think you should be more specific here in step two.” (Of course, I’ve been able to find the cartoon on the internet and will post it with this meditation.) It’s a familiar enough parable, this story of the farmer who sows his seed only to have most of it fail to produce for one reason or another. Jesus’ use of the broadcasting seed as a metaphor for preaching is reassuring to those of us who preach on a regular basis. It seems to say it isn’t our fault if what we preach has little or no impact on the hearers; it’s the fault of the “soils” into which we are sowing – maybe “Satan” snatched it away, or maybe the hearers have no “depth”, or maybe they are just too concerned with “cares of the world”.

It’s a familiar enough parable, this story of the farmer who sows his seed only to have most of it fail to produce for one reason or another. Jesus’ use of the broadcasting seed as a metaphor for preaching is reassuring to those of us who preach on a regular basis. It seems to say it isn’t our fault if what we preach has little or no impact on the hearers; it’s the fault of the “soils” into which we are sowing – maybe “Satan” snatched it away, or maybe the hearers have no “depth”, or maybe they are just too concerned with “cares of the world”.  Mark, Matthew, and John all report that on another occasion Jesus commented, “Prophets are not without honor except in their own country and in their own house.” One can’t get much more dishonored that being accused of being crazy!

Mark, Matthew, and John all report that on another occasion Jesus commented, “Prophets are not without honor except in their own country and in their own house.” One can’t get much more dishonored that being accused of being crazy! I held off offering a meditation on this Inauguration Day, the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday, for a variety of reasons. Throughout the day, however, this particular bit of St. Paul’s Letter to the Church at Ephesus kept returning to my mind. The Episcopal Church uses this in dialogue form in our baptismal liturgy, so it is familiar to us. The idea that we are all in some way united is a part of our Anglican ethos.

I held off offering a meditation on this Inauguration Day, the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday, for a variety of reasons. Throughout the day, however, this particular bit of St. Paul’s Letter to the Church at Ephesus kept returning to my mind. The Episcopal Church uses this in dialogue form in our baptismal liturgy, so it is familiar to us. The idea that we are all in some way united is a part of our Anglican ethos.