(This is not the sermon I preached on Sunday, November 13, 2011. It is not that sermon because I didn’t write that sermon down before preaching it … I didn’t even make an outline of that sermon before preaching it. This sermon [since I didn’t preach it, maybe that’s the wrong word] is what I wrote down several hours later – I think it contains some of what I said, expands on part of what I said, and probably leaves out some of what I said.)

Give us open minds, O God, minds ready to receive and to welcome such new light of knowledge as it is your will to reveal to us. Let not the past ever be so dear to us as to set a limit to the future. Give us courage to change our minds when that is needed. Let us be tolerant to the thoughts of others and hospitable to such light as may come to us through them. Amen.

A few days ago, a member of the congregation came to my office with that prayer. She said she’d found it in going through some of her old papers. It is a prayer attributed to John Baillie, who was a Church of Scotland minister in the mid-20th Century; in fact, he was the Moderator of the Church of Scotland during the 1940s. I think the three most important words in this prayer are “Give us courage” because they directly address the lesson of today’s reading from the Holy Gospel.

Let’s remember once again where we are in Scripture here at the end of Lectionary Year A of the Revised Common Lectionary’s cycle, the context of this lesson we have heard from the Gospel according to Matthew. For the past several weeks, we have been reliving the events of Holy Week as related in the closing chapters of Matthew’s Gospel. We have seen Jesus, after entering the city of Jerusalem, cleanse the Temple. You remember, he threw out the money changers, the bankers, the sellers of sacrificial animals, all those who were profiting from others’ religious devotion; “You will not make my father’s house a place of thievery!” he said to them.

Then we heard him in the Temple courtyard being confronted by Pharisees, Sadducees, Herodians, lawyers, and all sorts of powerful groups who wanted to test him, to trick him, to trap him in some ill-advised statement that might form the basis of a prosecution. They were trying to get rid of him, so they asked about taxes, about Commandments, about the after-life. But Jesus was too good a teacher, too good a debater to get caught in their traps and, by his questions, he silenced them and put an end to those confrontations.

Now with his disciples, a large group of his followers, not just his Twelve intimate companions, he is trying to explain what is going to happen next and what comes after that. He is trying to make them understand that he is probably going to be arrested and will quite likely die, but he is also trying to get them to appreciate that his death will not be the end of the story. He is trying to teach them that they have responsibilities that will continue past his execution, and that he will be back to judge how well they have done.

Following the same didactic method he has always used, he does this teaching through the medium of parables. First he tells a parable illustrating the Kingdom of Heaven as being like ten bridesmaids waiting with lamps to greet a bridegroom. Five were wise, conserved their oil, and were able to go into the celebration with the bridegroom, but five were foolish, used up their oil and had to go buy more. While they were away in the market place, the bridegroom came and they missed the party. “Be alert,” he says, “for you do not know when Judgment Day will come.”

Next he tells the parable set out in today’s Gospel reading (Matt. 25: 14-30), the story of the wealthy man going away and leaving his assets in the care of servants. As the text is set out in our Lectionary Book, it says, “Jesus said, ‘The Kingdom of Heaven is as if …” But those words, “The Kingdom of Heaven” are not found in these verses of Matthew’s 25th Chapter. All Matthew quotes Jesus as saying is “For it is as if ….” (v. 14) I don’t believe that the “it” Jesus is here describing is the Kingdom of Heaven at all. Rather, he is describing what will happen when he returns at that time about which we will “know neither the day nor the hour.” (v. 13) He is describing what theology calls “the parousia” – the last day, the judgment day, the winnowing at the end of time – when he, the Master, will return to receive “the account which we must one day give.” (Prayer for the Right Use of God’s Gifts, The Book of Common Prayer – 1979, pg. 827)

To fully understand this Parable to the Talents, we must appreciate not only this context, we must also understand what a “talent” is. I wonder sometimes why the translators of the Bible chose to transliterate the Greek word talonton in this way, why they didn’t translate that Greek word into something that would more clearly communicate the meaning of this story.

In our modern English, we hear the word talent and we immediately think of skills and abilities, the ability to sing a song or play an instrument, the ability to paint a picture or wire a computer; these are what we understand talents to be. But that is not what is meant here. To be blunt about it, what Jesus is talking about here is money! And not just a small amount of it.

Biblical historians tell us that a talent in the first century was an amount of money equal to fifteen to twenty times the average worker’s annual earnings. Let me say that again – fifteen to twenty times the average worker’s annual earnings. To put that in perspective …. in September the Bureau of the Census issued a report on the economic data collected in 2010 entitled Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010 (available online). In that report it shows that last year the median income of a single-male worker in the United States was about $35,000 (Table 1, page 6 of the report). Fifteen times that amount is more than a half-million dollars! So that’s one way to understand a talent – in terms of today’s earnings it would be $500,000 or a little more!

Another way to understand the value of a talent is this … Another definition of the word is that it was a measurement of gold – a talent was 80 pound of gold. 80 pounds! The price of gold today is $1,788 per ounce … per ounce! $1,788 times 16 times 80 yields the value of a talent as more than $2,288,000! This is no paltry sum the master in the parable entrusts to his servants…. even the one with regard to whom he has the least faith in his ability gets a huge amount of money, and at this rate the one who got the most to manage got more than $11,000,000!

So these three guys, these three servants get these huge sums of money to manage during the boss’s absence. Two of them invest the money in some way and over the time of the owner’s absence, however long that was, they double his money. When he returns, they present him the money and the earnings, and to each he says, “Well done, good and faithful servant; enter into the joy of your master.”

The third guy, the one who got the least, doesn’t do that. He, fearing his master’s possible displeasure, buries the money and when the boss returns he digs it up and gives it back to him. The master has not lost anything; he gets back exactly what he gave the servant, but how does he respond? “You wicked and lazy slave!” And he has the guy tossed into the outer darkness where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.

Now you have to understand that this would have absolutely shocked Jesus’ original audience. This is precisely what they would have been taught was the thing to do. The Pharisees, the rabbis of their day, taught that this is what the Law of Moses required. When someone entrusted you with an asset, you were expected to return that asset to them – no more, no less. The safest possible thing you could do, the Pharisees taught, was to bury the asset in a secret place so that you could later return it unwasted to its owner. And yet Jesus says this is a wicked and lazy thing to do, and worthy of nothing less than the punishment of banishment to the outer darkness.

Remember that this parable is told by Jesus to the disciples, to those to whom he is entrusting the most precious thing he can give them – his Gospel, his Good News, his ministry on earth, his church. He is saying to them that he will someday return and he will expect to see that that Gospel has been spread, that Good News proclaimed, that ministry performed, and that church grown, not simply conserved and held safe and secure.

This is a story in which Jesus commends his church to take risks, just like the two faithful servants who invested their master’s assets and earned a 100% profit … there is never return on investment if there is no risk. Jesus wants his church to take risks.

In his book, Five Practices of Fruitful Congregations, United Methodist Bishop Robert Schnase, writes about risk-taking mission and service. He writes this:

Risk-taking refers to “extraordinary opportunities for life-changing engagement with other people with steps into greater uncertainty, a higher possibility of discomfort, resistance, or sacrifice. Risk-taking mission and service takes people into ministries that push them out of their comfort zone, stretching them beyond the circle of relationships and practices that routinely define their faith communities.”

That sounds a lot like the prayer attributed to Sir Francis Drake that our Inviting the Future Capital Campaign Committee has chosen to guide us in that effort, that prayer that God will push us beyond our horizons, beyond our comfort zones, beyond our usual circles of relationship and practice. What most struck me about the bishop’s definition, though, was its recognition that risk-taking presents us with “a higher possibility of discomfort, resistance, or sacrifice.”

Many of you, I know, like to use the bible paraphrase The Message in your daily devotions and bible study. That paraphrase was written by Eugene Peterson, a retired Presbyterian pastor. In one of his other books, The Jesus Way, Eugene Peterson wrote this: “A sacrificial life is the means, and the only means, by which a life of faith matures.”

What both Schnase and Peterson are saying, what many Christian writers have said, is that Christianity is an adventure of the spirit or it is not Christianity. We must repent of our obsession with safety and security; we must be willing to take risks if we are going to do the tasks that only we as Jesus’ people can do! We must be willing to accept the risk that we may make mistakes. One of my favorite playwrights, George Bernard Shaw, who was not a Christian, once said, “A life spent making mistakes is not only more honorable but more useful than a life spent in doing nothing.” That, I think, is the point that Jesus is making, that Jesus is insisting upon in this parable.

The past few weeks in our lessons from the Hebrew Scriptures we have recalled the journey of the Chosen People from slavery in Egypt to freedom in the Holy Land. We have remembered how they crossed the Red Sea, how God gave Moses the ability to strike the water with his staff so that it parted and the sea floor became solid, dry ground that the people could cross. We have remembered how Joshua was instructed at the River Jordan to have twelve men representing the Tribes of Israel carry the Ark of the Covenant into the river where they were to stand, and as they did so the waters of the river ceased to flow so that the river bed became solid, dry ground that the people could cross. I am sure that there were some who, as they made that crossing, took small, timid steps, unsure and afraid as they went…. But we no longer have Moses with his magic rod; we no longer have the Ark to go before us. The Red Sea isn’t parting for us, and the river isn’t going to stop flowing. We don’t have the luxury of small, timid steps….

The river has carved a chasm, a great canyon, and if we are going to cross over from where we are to where Jesus expects us to be, we are going to have to take a leap of faith … you can’t cross a canyon with small, timid steps.

You’ve all heard that term before – “a leap of faith”? There are a couple of guys named Michael Frost and Alan Hirsch who have written a book encouraging the Church to embrace a theology of risk, adventure, and courage which they have titled by turning that phrase around. Their book is called The Faith of Leap! That is what Jesus in this Parable of the Talents is calling us to have, the Faith of Leap.

The past couple of days three members of this congregation and I attended our annual diocesan convention. One of the bits of business we do at that convention is to adopt a budget for the diocese in the coming year. We’re in the process of doing the same here in the parish – a committee is looking at our income and expenses and developing a financial plan for the Vestry to adopt for 2012. At the convention and in the parish each year we hear the same thing: “We have to pare down our expenses. We have to economize. We have to balance the budget. We have to be safe and secure and only do what we think we can afford to do.” We hear this everywhere in the church, at all levels, every year. It boils down to a cry to avoid risk.

I understand this inclination to security. Several years ago, before I was ordained, I was on the board of trustees of the church’s camp and conference center in the Diocese of Nevada, a facility called Camp Galilee. We had some maintenance that needed to be done – cabins needed reroofing, some cabins needed to be “winterized” so we could get greater year-round use out of the facilities, driveways and parking areas needed to be paved. A few of us on the board, myself included, felt we needed to be frugal and prudent; we believed we should not incur debt to do this work, but only do that part of it which we could afford. Our bishop was the late Wes Frensdorff, a man whom I have come to regard as one of the few true Saints I have ever known. Wes listened to us as we made our case for safety and security, and then replied, “A church that is not in debt is a church that is not doing its proper ministry.” It’s taken me years to understand what Bishop Frensdorff was saying … but I know now that he was simply following what Jesus is saying in this Parable of the Talents: we as Jesus’ church are called to be risk-takers.

You know … with regard to this parable, I have always thought that, when the Master returned, if the timid and fearful servant had, instead of burying the one talent, invested it in a losing proposition, that would have been alright. I’ve always thought that if he had said to the boss, “Look, I’m sorry; I lost your money. I’m just not as good a business man as these other two guys. I took the one talent and I invested it in what I thought was a good risk, but it didn’t turn out that way” the Master would have replied, “That’s OK! You tried. You gave it a good shot. Learn from your mistake, learn from your fellow servants. You’ll do better next time. Enter now into the joy of your master.”

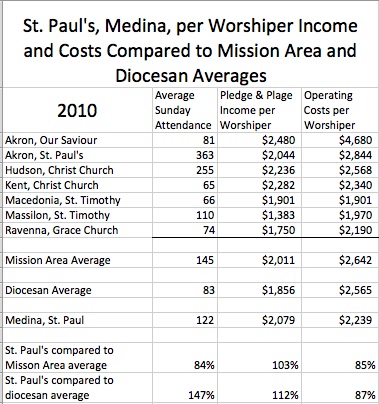

One of the pieces of information we are provided at the convention is a multi-page chart which gives us the “ASA” or “Average Sunday Attendance” of every church in the diocese. That chart also shows the annual plate-and-pledge income of every congregation and the annual operating expenses of every parish. And it includes a calculation of income per worshiper and expenses per worshiper. I took a close look at that data and prepared a little chart of my own comparing our figures to two things – the average of similar churches in our Mission Area and the average for the diocese. (By “similar churches” I mean those with full-time rectors and at least one other full- or part-time staff person.) Here is what I discovered:

What I discovered is that we run a very efficient church operation compared to other congregations. Our income per worshiper is 112% of the diocesan average, while our operating costs per worshiper are only 87% of the diocesan average. We spend only $2,239 per year for the ministry we at St. Paul’s Parish do with, for, and on behalf of each of you worshipers. You know, if I were, what I would say about that? I’d say, “How dare you! How dare you spend only $2,200 a year for me!” How dare we, indeed! Here you are of infinite worth to God Almighty, entrusted by God with the Good News of Christ, and we spend only a paltry $43 a week on your behalf! How dare we be so timid and fearful! This data says that we run a tight ecclesiastical ship … but, I’m sad to say, that means we don’t take much risk at all ….

And I believe this is true of the entire church, not just St. Paul’s, not just the Diocese of Ohio, not just the Episcopal Church, but the whole Christian community in the United States of America for at least the last four decades if not longer. We have, I believe, been burying our treasure, the deposit entrusted to us by our Master, in the sand … and not just our talent; we’ve been burying our heads in the sand as well.

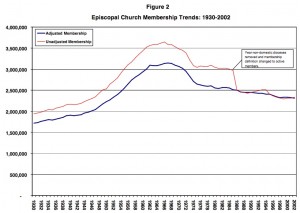

C. Kirk Hadaway, the statistical research maven at our national church headquarters, has published a series of reports on church growth (or perhaps one should say, “church shrinkage”) in the Episcopal Church. His graph of our membership data for the past several decades looks like this:

If you removed our denominational name from this graph, however, you wouldn’t be able to tell, from the shape and direction of the curve, which mainline denomination it represents. The membership graphs for the Lutherans, the Methodists, the Presbyterians, and others all look pretty much the same. The church has been shrinking … and I believe the reason is that we have been afraid to risk. We have sought the security and safety represented by balanced budgets; we have not taken the risks we have to take if we are to have the “faith of leap” that Jesus in this parable commends to us. We have become safe, secure …. and boring. Bishop Frensdorff had a coffee mug on which were the words “Budgets Are For Wimps”! We have become wimpy!

In the Book of Revelation, the Risen Christ directs the seer, John of Patmos, to write a series of letters to seven churches. To the Church in Laodicea John is directed to write: “I know your works; you are neither cold nor hot. I wish that you were either cold or hot. So, because you are lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I am about to spit you out of my mouth.” (Rev. 3:15-16) Without the “faith of leap,” without a willingness to take risks, no congregation, no denomination is hot or cold … with are pared-down, balanced budgets, we are merely tepid and timid, tasteless and wimpy, unworthy of anything but being spat out, consigned like the timid and fearful, wicked and lazy servant to the place of outer darkness where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.

Now please note that this Parable of the Talents is not a parable about personal stewardship. It is a parable directed to the entirety of Christ’s disciples, to the church as a whole. It is the church which has received this deposit of faith, this Gospel, this Good News; it is the church which Jesus expects to invest it, take necessary risks with it, nurture it, and return it to him – not as he left it with us, but as we have grown it during his time away. There may be here a teaching for each of us as individuals, but what each of us is to learn from it is for us personally to determine. And where that individual learning intersects with our corporate responsibility is for each of us to discern.

In the Parable of the Talents, the Master returned and to the first two servants, who faithfully used and increased what had been entrusted to them, he extended the greeting, “Well done, good and faithful servant, enter into the joy of your master.” To the timid and fearful servant who avoided risk for the safety and security of a hole in the ground, he gave the condemnation, “You wicked and lazy servant!”

At end of time, at the Parousia, on the last great day, at the Judgment … the Master will return, he will call us to account; we will return to him the church he has entrusted to us and he will say to us …..

(At this point I sat down…. After a few minutes, I asked the ushers to pass out a sheet containing the prayer which began the sermon and also the following commitment. I rose and asked the congregation to read it with me:)

My Church is composed of people like me.

I help make it what it is.

It will be friendly, if I am.

Its pews will be full, if I help fill them.

It will do great work, if I work.

It will make generous gifts to many causes, if I am a generous giver.

It will bring other people into its worship & fellowship if I invite them.

It will be a church of loyalty and love,

— of fearlessness and faith,

— and a church with a noble spirit

— if I, who make it what it is,

— am filled with these same things.Therefore, with the help of God,

I shall dedicate myself

to the task of being all the things that I want my church to be.

Give us courage, Lord! Give us the faith of leap! Amen.

You’re wrong.

You are interpreting this parable by the commandments of man not god.

Talents is not money, it is weight.

Expectations that are put on you that you MATCH, NOT DOUBLE.

The parable encourages risk taking and increasing, not sitting idle. As for “talent,” yes, it’s weight. But it’s specifically a weight of precious metal; in other words, money. Thanks for your feedback.