The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.”[1] While recent polling data demonstrate that the influence of religion seems to have declined, it remains a powerful force.

The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.”[1] While recent polling data demonstrate that the influence of religion seems to have declined, it remains a powerful force.

According to an average of all 2023 Gallup polling, about 75% of Americans identify with a specific religious faith, and 71% say that religion is either “important” or “very important” in their lives; over 40% attend religious services at least monthly, more than half of those weekly.[2]

But there is “important” and there is “important”; there is “religious” and there is “religious.” Is a religion “important” to someone in that that person spends a good deal of time observing its outward rituals, or is it “important” in that its moral precepts form a significant underpinning of his or her social behavior? Is a person “religious” because they make large donations or sacrifices and frequently attend significant rituals and ceremonies, or because he or she is an ethical and compassionate person who stands for justice and equity?

In de Tocqueville’s observations of America, it was the latter. He praised American religion for its comparative simplicity and its elimination of ritual: “I have seen no country,” he wrote, “in which Christianity is clothed with fewer forms, figures, and observances than in the United States.”[3] For the Prophet Amos in ancient Israel, the problem was the former. As biblical scholar and professor of Old Testament F.B. Huey, Jr., has noted:

Amos appeared on the scene in Israel during the reign of Jeroboam II, a time of relative peace and prosperity in both Israel and Judah. Some of the people enjoyed great wealth, but others experienced crushing poverty. The poor were oppressed, cheated, and exploited. Their rights were ignored. Immorality of every kind was openly and unashamedly practiced. Drunkenness, adultery, licentiousness, and self-indulgence had rotted the moral fiber of the nation.

However, the people could not be accused of neglecting religion. Ritualistic practices abounded. High places for worship of other gods were tolerated. Idolatry was not suppressed. [Professor John] Paterson’s classic statement best sums up the situation: “The people were oozing and dripping with religion of a kind.”[4]

About 170 years before Amos, around the year 930 BCE, the People of Israel had divided themselves into two kingdoms. The ten tribes whose territory was north of Jerusalem revolted against King Solomon’s son Rehoboam and formed a new kingdom, taking the name Israel, under Jeroboam I, who had been the official over Solomon’s public construction programs. The tribes of Judah and Benjamin, together with the Levites who served the Jerusalem Temple, remained loyal to Rehoboam and formed the southern Kingdom of Judah.

The northern kingdom established two centers of worship; one at Dan and the other at Shechem. The temples that were built at these places displayed statues of golden calves as symbols of God; they were even emblazoned with the four-letter ineffable name “YHWH”. Worship and sacrifice were performed by non-Levite priests appointed by the king.[5]

Jeroboam I was succeeded by several kings, nearly all of whom, according to Scripture, “did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, walking in the way of Jeroboam and in the sin that he caused Israel to commit,”[6] some worse than others. And after 170 years, Jereboam II took the throne. His reign was one of military success and triumph against Israel’s enemies and neighbors, and of extraordinary wealth for the king and his aristocrats. Jewish tradition records

The triumphs of the king had engendered a haughty spirit of boastful overconfidence at home. Oppression and exploitation of the poor by the mighty, luxury in palaces of unheard-of splendor, and a craving for amusement were some of the internal fruits of these external triumphs.[7]

It is against this profligate extravagance, and the injustice and iniquity that accompanied it, that Amos spoke out.

Amos was a native of Judah, from the town of Tekoa, ten miles south of Jerusalem, but he was sent by God to prophesy in the Northern Kingdom. The central message of his prophecy is summed up in four verses in which God says:

I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt-offerings

and grain-offerings, I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.[8]

Amos testified to what has been called the “seamless relationship between ethical behavior and true worship, between justice and piety.”[9] The latter without the former is hollow and worthless. It’s no wonder Amaziah the priest told him to return to Judah and never prophesy in Israel again. I’m sad to say that I suspect that Amos would receive no better welcome in parts of modern-day America, for all our reported religiosity. In any event, for its injustice, its corruption, and its ritualistic but morally bankrupt religion, Amos prophesied the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel, and it came to pass.

Nearly eight centuries later, Judah had also ceased to exist and the whole of Palestine had been absorbed into the Roman Empire. The last king of anything that could be called a unified Jewish nation, Herod the Great, King of Judea, had died and the Romans (confirming instructions in Herod’s will) divided his client kingdom among his children. His youngest son, Herod Antipas, ruled, under the title of “Tetrarch,” a portion of what had been Jeroboam’s kingdom and, like Jeroboam, he had to contend with a prophet condemning the morality and injustice of both his political reign and his personal lifestyle.

Luke rather white washes or sugar coats John’s social justice prophecy, making it sound like an adult Bible Study class:

[T]he crowds asked him, “What then should we do?” In reply he said to them, “Whoever has two coats must share with anyone who has none; and whoever has food must do likewise.” Even tax-collectors came to be baptized, and they asked him, “Teacher, what should we do?” He said to them, “Collect no more than the amount prescribed for you.” Soldiers also asked him, “And we, what should we do?” He said to them, “Do not extort money from anyone by threats or false accusation, and be satisfied with your wages.”[10]

But remember, John was also talking to the religious authorities, the Pharisees, the Sadducees, and “all the people from Jerusalem,”[11] the same people he had just addressed as “You brood of vipers!” and called a bunch of rotten trees producing bitter fruit which God plans to chop down and throw into the fire![12] I would think the conversation was a little more heated than the polite Sunday School class Luke describes.

It was not John’s concerns about neglect of the poor, excessive taxation, or military oppression that got him arrested and beheaded, however; it was his criticism of the Tetrarch’s marriage. History tells us that Antipas occasionally paid heed to the outward norms and forms of contemporary Judaism: “[H]e is known to have celebrated Passover and Sukkoth in Jerusalem. Unfortunately, his subjects were not convinced by their leader’s piety.”[13] He’d been educated in Rome, venerated the Emperor Tiberius, and in his personal life, especially it seems in regard to marriage, he was pretty much culturally a Roman.

Initially, he was in a political marriage to Phasaelis, daughter of King Aretas IV of Nabatea, a neighboring country. But then he met Herodias, the wife of his half-brother Archelaus. They fell in love and each divorced their current spouse so they could marry the other. While marriage to the ex-wife of one’s living brother was not against Roman law, it was not acceptable under the Law of Moses. On top of that, Herodias was also his niece, the daughter of his other half-brother, Aristobulus. Again, marriage to one’s niece was permitted under Roman law, but outside the bounds Jewish propriety. John called him out on it, and this is what got John arrested and eventually beheaded.

Like Jeroboam and Amaziah, Herod Antipas and the religious leaders of Jerusalem adhered to the outward trappings of religion, but within those rituals there was little or no ethical content; worse, there was unrighteousness, injustice, and immorality. They were, as Jesus would later say, like whited sepulchres, “which on the outside look beautiful, but inside they are full of the bones of the dead and of all kinds of filth.”[14]

Amos of Tekoa and John the Baptizer were followers of the God of Israel who called those who claimed to be their co-religionists to task. They sang from the same hymnal as all the prophets who called on God’s People to “do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with … God,”[15] and they invite us to sing from that hymnal, as well, for we also have co-religionists to correct.

There is, as you know, a growing movement in our country and within the church called “dominionism” or “Christian nationalism.” It is, primarily, a phenomenon of white evangelicalism. It is quite simply a heresy. Dressed up in the rituals and ceremonies of the Christian faith, it promotes something very different from the love, justice, and humility taught by Jesus and all the prophets before him. But we cannot, as many have tried, simply dismiss dominionism as “not Christian” anymore than Amos or John could wash their hands of Jeroboam, Antipas, and their religious leaders as “not really following the religion of YHWH.”

As historian Jemar Tisby says:

[W]hite Christian nationalism is Christian, not because it resembles Christ but because it’s in the church.

White Christian nationalists attend church. They may not be the kind of churches you would want to join, but they are there.

White Christian nationalists look to the same sacred text, the Bible, that other Christians do. It may not be how you interpret scripture, but it’s the same book.

White Christian nationalists would largely claim the resurrection of Jesus, the Trinity, and other core, historical Christian doctrines. They may not derive the same meaning from those theological principles as you do, but they believe them.

White Christian nationalists use Christian symbols and rituals—crosses, prayers, spiritual songs, and fasting. These may not soften their souls in the ways we’d expect, but they are present nonetheless.[16]

No, Christian nationalism does not “soften the souls” of its adherents; on the contrary, it rather remarkably hardens their hearts. As described by Evangelicals for Democracy, Christian dominionism

treat[s] minorities and non-Christians as second-class citizens [and promotes] voting restrictions on a massive scale; more aggressive police tactics targeting black and brown communities; prohibiting interracial marriage and transracial adoption; ending protections for the religious liberty of Jews, Muslims and other non-Christian faiths; … enacting policies that are hostile to immigrants and refugees [and] the belief that women should be subservient to men.[17]

Dr. Tisby argues that the dominionists’ “misuse of the term ‘Christian’” imposes on other believers, that is us, “the duty to set forth an alternative witness of the faith.”[18]

The message of the prophets, of Amos and John, is clear: the God of Israel, the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, demands morality, ethical conduct, justice, and equity. When de Tocqueville described the contribution of the Christian religion in America he wrote that it “impos[ed] some degree of humaneness on [the country’s] competitive, materialistic society.” His description of religion in the early days of the Republic differs dramatically from the program of the Christian nationalists; he observed religion that “placed mankind’s objectives beyond the treasures of earth and the soul above the senses,” that “imposed on human beings some responsibility for the welfare of others and compelled them to contemplate concerns other than their own.”[19] This religion, with its “seamless relationship between ethical behavior and true worship, between justice and piety”[20] is and has always been the “alternative witness of the faith” in this nation that we, like Amos and John before us, are to proclaim to the rulers and the people of our time.

Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Eighth Sunday after Pentecost, July 14, 2024, to the people of Harcourt Parish (Church of the Holy Spirit), Gambier, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest presider and preacher.

The lessons for the service were Amos 7:7-15; Psalm 85:8-13; Ephesians 1:3-14; and St. Mark 6:14-29. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.

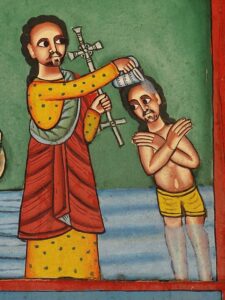

The illustration is an 18th-century Russian icon of the prophet Amos from the Iconostasis of Transfiguration Church, Kizhi monastery, Karelia, Russia.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Quoted in Norman A Graebner, Christianity and Democracy: Tocqueville’s Views of Religion in America, The Journal of Religion 56:3 (July 1976), p. 263

[2] How Religious Are Americans?, Gallup, March 29, 2024, accessed 11 July 2024

[3] Quoted in Graebner, op. cit., p. 265

[4] F.B. Huey,, Jr., The Ethical Teaching of Amos, Its Content and Relevance, Southwestern Journal of Theology, Vol. 9, Fall 1966, quoting John Paterson, The Goodly Fellowship of the Prophets (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York:1948), p. 25, online at Preaching Source, accessed 11 July 2024

[5] See 1 Kings 12

[6] 1 Kings 15:34 (NRSV)

[7] Emil G. Hirsch, Jeroboam, Jewish Encyclopedia, undated, accessed 11 July 2024

[8] Amos 5:21-24 (NRSV)

[9] Eldin Villafane, To Live in Justice: The Message of Amos For Today, Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary, October 24, 2016, accessed 11 July 2024

[10] Luke 3:10-14 (NRSV)

[11] See Matthew 3:7 and Mark 1:5

[12] Luke 3:7,9

[13] Herod Antipas, Livius: Articles on Ancient History, August 4, 2020, accessed 12 July 2024

[14] Matthew 23:27 (NRSV). The term “whited sepulchres” is taken from the King James Version.

[15] Micah 6:8 (NRSV)

[16] Jemar Tisby, Is White Christian Nationalism Christian?, Footnotes by Jemar Tisby, January 17, 2024, accessed 11 July 2024

[17] The Truth About Christian Nationalism, Evangelicals for Democracy, undated, accessed 12 July 2024

[18] Tisby, op. cit.

[19] Graebner, op. cit., pp. 269-70

[20] Villafane, op. cit.

There’s a story about a pastor giving a children’s sermon. He decides to use a story about forest animals as his starting point, so he gathers the kids around him and begins by asking them a question. He says, “I’m going to describe someone to you and I want you to tell me who it is. This person prepares for winter by gathering nuts and hiding them in a safe place, like inside a hollow tree. Who might that be?” The kids all have a puzzled look on their faces and no one answers. So, the preacher continues, “Well, this person is kind of short. He has whiskers and a bushy tail, and he scampers along branches jumping from tree to tree.” More puzzled looks until, finally, Johnnie raises his hand. The preacher breathes a sigh of relief, and calls on Johnnie, who says, “I know the answer is supposed to be Jesus, but that sure sounds an awful lot like a squirrel to me.”

There’s a story about a pastor giving a children’s sermon. He decides to use a story about forest animals as his starting point, so he gathers the kids around him and begins by asking them a question. He says, “I’m going to describe someone to you and I want you to tell me who it is. This person prepares for winter by gathering nuts and hiding them in a safe place, like inside a hollow tree. Who might that be?” The kids all have a puzzled look on their faces and no one answers. So, the preacher continues, “Well, this person is kind of short. He has whiskers and a bushy tail, and he scampers along branches jumping from tree to tree.” More puzzled looks until, finally, Johnnie raises his hand. The preacher breathes a sigh of relief, and calls on Johnnie, who says, “I know the answer is supposed to be Jesus, but that sure sounds an awful lot like a squirrel to me.” We “boast in our sufferings,” writes Paul to the Romans, “knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us….”

We “boast in our sufferings,” writes Paul to the Romans, “knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us….” Come Holy Spirit, Comforter, Spirit of Truth,

Come Holy Spirit, Comforter, Spirit of Truth,

This is a special Sunday for me. Friday marked the 28th anniversary of my ordination as a priest in the Episcopal Church. It was on Sunday, June 23, 1991, that I celebrated my first mass. So I am grateful to you and to Fr. George for the privilege of an altar at which to celebrate the Holy Mysteries and a pulpit from which to preach the gospel on this, my anniversary Sunday.

This is a special Sunday for me. Friday marked the 28th anniversary of my ordination as a priest in the Episcopal Church. It was on Sunday, June 23, 1991, that I celebrated my first mass. So I am grateful to you and to Fr. George for the privilege of an altar at which to celebrate the Holy Mysteries and a pulpit from which to preach the gospel on this, my anniversary Sunday. Five weeks ago we began our month long journey through the world of bread with what Presbyterian scholar Choon-Leon Seow called the “remarkably mundane” story of food for the hungry, the feeding of the 5,000.

Five weeks ago we began our month long journey through the world of bread with what Presbyterian scholar Choon-Leon Seow called the “remarkably mundane” story of food for the hungry, the feeding of the 5,000. Children, as those of us who have had or who have been children know, grow in their ability to communicate. Vocabularies grow. Grammars develop. They move from simple one- or two-syllable concepts – such as “Mama” or “Dada” or “NO!” – to more complex ideas.

Children, as those of us who have had or who have been children know, grow in their ability to communicate. Vocabularies grow. Grammars develop. They move from simple one- or two-syllable concepts – such as “Mama” or “Dada” or “NO!” – to more complex ideas. At the end of our gospel lesson this morning, Jesus said to the crowd, “It is my Father who gives you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.” They said to him, “Sir, give us this bread always.” Jesus answered, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.”

At the end of our gospel lesson this morning, Jesus said to the crowd, “It is my Father who gives you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.” They said to him, “Sir, give us this bread always.” Jesus answered, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.” In 2014, Evie and I were privileged to join a group of other pilgrims from Ohio and Michigan and spend not quite three weeks in Palestine and Israel visiting many of the sites we hear about in the Bible, especially the Christian holy places of the Gospel stories. One of those was a hilly place overlooking the Sea of Galilee called Tabgha. Until 1948, when the Israelis uprooted its residents, a village had been there for centuries; now it is simply an agricultural area and a place of religious pilgrimage.

In 2014, Evie and I were privileged to join a group of other pilgrims from Ohio and Michigan and spend not quite three weeks in Palestine and Israel visiting many of the sites we hear about in the Bible, especially the Christian holy places of the Gospel stories. One of those was a hilly place overlooking the Sea of Galilee called Tabgha. Until 1948, when the Israelis uprooted its residents, a village had been there for centuries; now it is simply an agricultural area and a place of religious pilgrimage.