There’s a story about a pastor giving a children’s sermon. He decides to use a story about forest animals as his starting point, so he gathers the kids around him and begins by asking them a question. He says, “I’m going to describe someone to you and I want you to tell me who it is. This person prepares for winter by gathering nuts and hiding them in a safe place, like inside a hollow tree. Who might that be?” The kids all have a puzzled look on their faces and no one answers. So, the preacher continues, “Well, this person is kind of short. He has whiskers and a bushy tail, and he scampers along branches jumping from tree to tree.” More puzzled looks until, finally, Johnnie raises his hand. The preacher breathes a sigh of relief, and calls on Johnnie, who says, “I know the answer is supposed to be Jesus, but that sure sounds an awful lot like a squirrel to me.”

There’s a story about a pastor giving a children’s sermon. He decides to use a story about forest animals as his starting point, so he gathers the kids around him and begins by asking them a question. He says, “I’m going to describe someone to you and I want you to tell me who it is. This person prepares for winter by gathering nuts and hiding them in a safe place, like inside a hollow tree. Who might that be?” The kids all have a puzzled look on their faces and no one answers. So, the preacher continues, “Well, this person is kind of short. He has whiskers and a bushy tail, and he scampers along branches jumping from tree to tree.” More puzzled looks until, finally, Johnnie raises his hand. The preacher breathes a sigh of relief, and calls on Johnnie, who says, “I know the answer is supposed to be Jesus, but that sure sounds an awful lot like a squirrel to me.”

My best friend (another retired priest) and I often ask one another, “What are you preaching about on Sunday?” and our answer is always “Jesus.” For a preacher, the answer is always supposed to be Jesus. We’re supposed to take Paul as our model; he wrote to the Corinthians, “When I came to you, brothers and sisters, I did not come proclaiming the mystery of God to you in lofty words or wisdom. For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified.”[1] So we are to do the same, preach Christ and him crucified, or perhaps today preach Christ and him baptized.

On the other hand, a recommended method of sermon preparation is the ancient practice of lectio divina in which one reads the text aloud multiple times while listening for the one word or phrase that captures one’s attention, then explore that word or phrase in prayer and meditation.[2] When I did that over the past couple of weeks, what capture my imagination was the river. So I decided to preach about the River Jordan.

In 2014, my wife Evelyn and I were privileged to make a three-week pilgrimage to Palestine and Israel, and one of the things we did was to visit the River Jordan near Jericho and reaffirm our baptismal vows. We didn’t go to one of the three places that officially claim to be the site of Jesus’ baptism; we were just at some place along the banks of the lower Jordan between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea further south. I don’t know whether we were in Israel proper or somewhere in the occupied West Bank, but I do know that across the river we could see Jordan. You see, the Jordan River is what is known in international law as a “transboundary water,” which means it lies along and crosses international boundaries. One of the largest transboundary water systems in the world is just a short distance north of here, the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River; both the U.S. and Canada have some claim on those waters, and those who boat or fish or swim or sail those waters can easily find themselves crossing the border from one nation to the other without even knowing it, as I’m sure you know. With regard to the Jordan, the nations of Lebanon and Syria, where the its headwaters are found, and Israel, Palestine, and Jordan, along whose borders the river runs, all have some claim on the river.

While I thought and prayed about the Jordan as a transboundary river, I remembered an old spiritual you may be familiar with, I Am a Poor Wayfaring Stranger. There are many variations of the old song; the one I learned is this:

I am a poor wayfaring stranger,

Traveling through this world of woe,

And there’s no sickness, toil, or danger,

In that bright land to which I go.

I’m going there to meet my Father,

He said he’d meet me when I come.

I’m only going over Jordan,

I’m only going over home.I know dark clouds will gather o’er me,

I know my way lies rough and steep

But Beauteous Fields lie out before me

Where God’s redeemed their vigils keep.

I’m going there to meet my Father,

He said he’d meet me when I come.

I’m only going over Jordan,

I’m only going over home.[3]

As I sang that song to myself, it occurred to me that the Jordan is a transboundary river not only between and amongst those Middle Eastern nations, but between the world and Heaven, something we see demonstrated in all of four gospel accounts of Jesus’ baptism. When John immerses Jesus in the Jordan the spiritual world is opened, the Holy Spirit descends and the Father’s voice is heard, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.”[4]

In Celtic spirituality, it is said that Heaven and earth are only three feet apart, but there are thin places where that distance is even shorter. These are “places where the boundary between the mundane and the eternal becomes permeable. God parts the curtain, and we catch glimpses of his love, majesty, and power.”[5] The River Jordan is such a place.

The 3rd Century church father Origen, head of the catechetical school in Alexandria, in a homily on the Prophet Joshua, said that every baptismal font is the Jordan, that those who are baptized “have passed through Jordan’s stream by the sacrament of baptism.”[6] When you were baptized, wherever it happened, you were bathed in the waters of the Jordan River. In that moment that place became a transboundary water between earth and Heaven; in that moment that place became thin. Though no one may have seen it, the Holy Spirit descended and, though no one may have heard it, the Father said, “You are my beloved child.”

You became, as Paul wrote in several places, God’s child by adoption;[7] you became a “thin person.” This, says Canadian Mennonite Troy Watson, is Jesus’ mission:

…. to create “thin people,” meaning people of all shapes and sizes who embody a presence that is divine—in every sense of the word. This is who and what Jesus was—the ultimate thin place—where God and humanity existed in the same time and place. To be Christ-like is to be “thin” in that we are mobile “places” where the Divine permeates physical reality.[8]

This is what happens in baptism. In John’s Gospel, Jesus promises that his followers will have within them “a spring of water gushing up to eternal life,”[9] and that “out of the believer’s heart shall flow rivers of living water.”[10] These “rivers of living water,” said Hildegarde of Bingen, “are to be poured out over the whole world, to ensure that people . . . can be restored to wholeness.”[11]

The droplets of water on a [candidate’s] forehead in baptism in a moment of time symbolise an eternity of goodness flowing from the heart of God, a river of love that seeks unendingly to reproduce itself in the lives of people. * * * Baptism is a big agenda of generosity, a promise of hope and change, for us and for our world, a sharing in the ongoing life of Christ and the love of God for all humanity.[12]

In a New York Times article several years ago, travel writer Eric Weiner asked, “If God (however defined) is everywhere and ‘everywhen,’ as the Australian aboriginals put it so wonderfully, then why are some places thin and others not? Why isn’t the whole world thin?” And then he answered his own question, “Maybe it is but we’re too thick to recognize it.”[13] Perhaps that is, fundamentally, our purpose as people of God and as followers of Christ: the “living water” that flows from us, like a little bit of the Jordan River, is meant to reveal to others the thinness of creation, the reality of goodness and grace. As “thin people,” we are to join with God in opening thin places where the grace of Jesus Christ can bring about the healing and wholeness of the world.

So, when all is said and done, although the answer to what I was going to preach about looked an awful lot like the River Jordan, it turned out to be Jesus. The answer is always Jesus. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the First Sunday after Epiphany (The Baptism of Our Lord), January 7, 2024, to the people of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, Elyria, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest presider and preacher.

The lessons were from the Revised Common Lectionary, Year B, Epiphany 1: Genesis 1:1-5; Psalm 29; Acts 19:1-7; and St. Mark 1:4-11. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

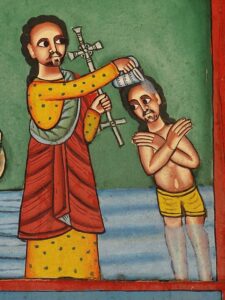

The illustration is Depiction of the Baptism of Jesus in Axum, Ethiopia, photograph by Adam Jones at Wikipedia.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] 1 Corinthians 2:2-3 (NRSV)

[2] See Geoff New, Preaching and the Imagination, in Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry, Vol. 43, No. 43 (Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver: 2023), pp 167-76

[3] A slightly different version is found at Wayfaring Stranger, Hymnary.org, accessed 5 January 2024

[4] Mark 1:11 (NRSV)

[5] Debie Thomas, Thin Place, Deep Water, Journey with Jesus, January 1, 2017, accessed 5 January 2024

[6] Origen, Excerpt from a homily on Joshua (Hom 4, 1: PG 12, 842-843), Crossroads Initiative, June 13, 2017, accessed 5 January 2023

[7] See, e.g., Romans 8:15, Galatians 4:5, and Ephesians 1:5

[8] Troy Watson, Moving thinward (Pt. 4), Canadian Mennonite, May 20, 2015, accessed 6 January 2024

[9] John 4:14 (NRSV)

[10] John 7:38 (NRSV)

[11] Quoted in Sara Salvadori, Hildegard von Bingen: A Journey into the Images (Skira, Milan:2019), p 15

[12] William Loader, Baptism, Water, and Our World, billloader.com, undated, accessed 6 January 2024

[13] Eric Weiner, Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer, New York Times, March 9, 2012, accessed 6 January 2024

Leave a Reply