One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”[1] or, as it is put in this Gospel, “from now on you will be catching people,”[2] is to figure out if he’s referring back to Law or the Prophets, and whether it might be the lectionary’s choice for a first lesson. Sometimes that helps me figure out whether there is a thematic link between the lessons and, if so, what it’s supposed tell us, but unfortunately that’s not the case today. Jesus doesn’t seem to have had Isaiah in mind when he summoned Peter and his business partners.

One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”[1] or, as it is put in this Gospel, “from now on you will be catching people,”[2] is to figure out if he’s referring back to Law or the Prophets, and whether it might be the lectionary’s choice for a first lesson. Sometimes that helps me figure out whether there is a thematic link between the lessons and, if so, what it’s supposed tell us, but unfortunately that’s not the case today. Jesus doesn’t seem to have had Isaiah in mind when he summoned Peter and his business partners.

So for the past week or so, I’ve been pondering what might be the reason for putting the Isaiah reading –– which, although it comes in the sixth chapter, is the story of Isaiah’s initial call to be a prophet –– together with Luke’s version of Jesus recruiting Simon Peter and the sons of Zebedee, James and John, to be disciples. The simple answer, of course, is that they are both stories of calls to ministry, but they are so different!

I understand that St. Andrew’s Parish is, today, beginning its annual stewardship campaign, so I suppose it’s appropriate that we heard the story of Jesus being confronted by the wealthy man who wants to inherit eternal life in today’s Gospel reading from Mark. This tale must have been an important one to the earliest Christians, because we find it in all three of the Synoptic Gospels. Mark tells us only that the man is wealthy; Matthew adds that he is young; and Luke informs us that he is a ruler of some sort. But none of those details really changes the basic nature of the encounter: a potential disciple comes to Jesus seeking guidance and Jesus tells him that he must give up everything he possesses – “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor….”

I understand that St. Andrew’s Parish is, today, beginning its annual stewardship campaign, so I suppose it’s appropriate that we heard the story of Jesus being confronted by the wealthy man who wants to inherit eternal life in today’s Gospel reading from Mark. This tale must have been an important one to the earliest Christians, because we find it in all three of the Synoptic Gospels. Mark tells us only that the man is wealthy; Matthew adds that he is young; and Luke informs us that he is a ruler of some sort. But none of those details really changes the basic nature of the encounter: a potential disciple comes to Jesus seeking guidance and Jesus tells him that he must give up everything he possesses – “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor….” “They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats.”

“They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats.” The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.”

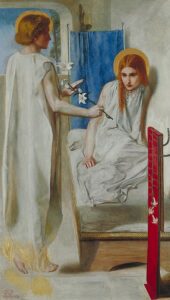

The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.” When I was about 8 or 9 years of age, my grandparents gave me an illustrated bible with several glossy, color illustrations of various stories. They weren’t great art, but they were clear and very expressive. My favorite amongst them was the illustration of today’s gospel lesson.

When I was about 8 or 9 years of age, my grandparents gave me an illustrated bible with several glossy, color illustrations of various stories. They weren’t great art, but they were clear and very expressive. My favorite amongst them was the illustration of today’s gospel lesson. Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter.

Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter. When I find myself in times of trouble,

When I find myself in times of trouble, John, your parish secretary, puts together a mailing every week that he sends to the clergy who will be joining you as presiders and preachers. He includes in that mailing some of the material from an Augsburg Fortress publication called “Sundays and Seasons,” which is a great lectionary resource. The illuminations that your lectors read before each Bible reading giving a little introduction about the lesson come from “Sundays and Seasons.” I’ve been familiar with the publication for a long time, though I’ve never been a subscriber: I used to participate in a weekly ecumenical lectionary study group that included Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, and Episcopal clergy and our Lutheran colleagues often brought something from “Sundays and Seasons” into our discussions.

John, your parish secretary, puts together a mailing every week that he sends to the clergy who will be joining you as presiders and preachers. He includes in that mailing some of the material from an Augsburg Fortress publication called “Sundays and Seasons,” which is a great lectionary resource. The illuminations that your lectors read before each Bible reading giving a little introduction about the lesson come from “Sundays and Seasons.” I’ve been familiar with the publication for a long time, though I’ve never been a subscriber: I used to participate in a weekly ecumenical lectionary study group that included Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, and Episcopal clergy and our Lutheran colleagues often brought something from “Sundays and Seasons” into our discussions.  We have three intriguing lessons from scripture today. First we have a denunciation of Hebrew worship, which also interestingly contains a verse most famous in American politics for having been spoken on the steps of the Lincoln monument by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Some people who dislike liturgy, or some aspect of liturgy, like incense, or vestments or music, ignoring that sentence about justice flowing like streams, have used this text to prove that God also dislikes, liturgy, or incense, or vestments, or whatever. However, that’s not what this lesson is about and I’ll get back to that in just a moment.

We have three intriguing lessons from scripture today. First we have a denunciation of Hebrew worship, which also interestingly contains a verse most famous in American politics for having been spoken on the steps of the Lincoln monument by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Some people who dislike liturgy, or some aspect of liturgy, like incense, or vestments or music, ignoring that sentence about justice flowing like streams, have used this text to prove that God also dislikes, liturgy, or incense, or vestments, or whatever. However, that’s not what this lesson is about and I’ll get back to that in just a moment.