Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter.

Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter.

Six days before, Jesus had had a conversation with the Twelve in which he’d asked them who they thought he was. They had said that other people thought Jesus might be a prophet and that some thought he might even be Elijah returned from Heaven or John the Baptizer returned from the dead. Jesus put them on the spot, though, and asked, “But who do you say I am?”[1] Peter answered, “You are the Messiah.”

Then they had an argument! Jesus congratulated Peter for his astute answer and then tried to explain to him and the others what that would mean predicting his own death in Jerusalem. Peter, headstrong and outspoken, had contradicted Jesus and vowed that they would never let that happen. That’s when Jesus called him “Satan” and told Peter to stop obstructing him. “Get behind me,” he said.[2] Then he told the rest of them that to be his disciple would mean suffering and probably death. “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.”[3]

So nearly a week has passed now and here on the Holy Mountain (traditionally believed to be Mt. Tabor about six miles east of Nazareth) Peter, James, and John behold what John would later refer to as Jesus’ “glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth.”[4] Peter would report that they had been “eyewitnesses of [Christ’s] majesty” when “he received honor and glory from God the Father.”[5] In some way, Jesus was transfigured, a word that describes a change in outward form or appearance, usually implying exaltation or glorification. Whatever it was that happened, these disciples would come to understand that Peter’s answer a week before, that Jesus was “the Son of the living God,”[6] meant much more than they had thought. In the Judaism of their time, it could refer to anyone of particularly noteworthy piety which the disciples believed their rabbi Jesus to be.[7]

Jesus “ordered them to tell no one about what they had seen, until after the Son of Man had risen from the dead.”[8] At some point, however, they must have told the story to someone, else we would not find it in the Gospels. And in the story they told not only of Jesus’ change in appearance, but of the voice from Heaven, a voice which spoke even as Peter was talking about building monuments to what was happening. As bible scholar David Lose describes the scene,

There is Peter, falling all over himself looking for something to do, when the voice from heaven literally interrupts him, saying (almost!), “Would you shut up already, and just listen to him!”[9]

I find it both amusing and disappointing that when Peter writes his second letter and describes the voice and what was said, he leaves off those last three words, “Listen to him.” It is so like Peter, and so like the church which he represents, to ignore and even forget those three words that Professor Warren Carter of Brite Divinity School has characterized as a “divine plea.”[10] As the priest-blogger who calls himself “the Listening Hermit” says,

[This] is something the disciples, and the church they founded, is not good at. We are unable to really listen to Jesus.[11]

I believe those three words spoken by God to Peter, James, and John, and through them to us, may be the most important divine admonition in the whole of the New Testament, perhaps in all of Holy Scripture. “Listen to him!”

It has occurred to me that there are two ways in which we don’t listen fully to Jesus. One way is that although we may know what it is that he said, we don’t hear it as coming from Jesus the Son of God. The other way is that although we may recognize Jesus as the Lord of creation, we don’t hear his words.

The first way to fail to listen to Jesus is represented by Thomas Jefferson. As you may know, Jefferson was an Episcopalian, a vestryman in his Virginia parish, and very well versed in Scripture. But he was also a free-thinker who really didn’t believe in the divinity of Jesus, so he edited the New Testament, apparently using a pen knife to cut out and rearrange the portions he liked best to produce a text more to his own taste.

Jefferson produced [an] 84-page volume . . . bound it in red leather and titled it The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. * * * [He] elected to not include related miraculous events, such as the feeding of the multitudes with only two fish and five loaves of barley bread; he eschewed anything that he perceived as “contrary to reason.”[12]

Basically what he did was take out anything that suggested Jesus’ divinity, reducing the Son of God to nothing more than a philosopher. When the words of Jesus are not those of God but merely those of a man, no matter how morally upright and impressive he may be, we do not hear them with the same import; the words of a mere man, no matter how moral and inspiring he may be, simply do not carry the same weight as the words of God. Indeed, C.S. Lewis argued that we should give them no weight at all. In a BBC broadcast later published in the book Mere Christianity, he said:

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I’m ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don’t accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell.[13]

If we take Jefferson’s approach, we do not listen to Jesus.

That first way is also represented by someone rather less imposing than Mr. Jefferson, and that is the title character of the Will Farrell movie, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby.[14] If you have seen the movie you may remember the Thanksgiving Dinner scene in which Ricky Bobby offers the table grace which he begins with these words, “Dear Lord baby Jesus . . . .” After he is interrupted by his friend Cal, he begins again, “Dear Lord baby Jesus . . . .” at which point his wife Carley interrupts him saying, “You know, sweetie, Jesus did grow up. You don’t always have to call him, ‘Baby.’ It’s a bit odd and off-putting to pray to a baby.” And Ricky responds, “Well, I like the Christmas Jesus best.” At that point, the offering of prayer is abandoned and the family begins a discussion of what image of Jesus each prefers. When Ricky does finally get back to the prayer, he addresses our Lord as: “Dear tiny Jesus in your golden-fleece diapers . . . Dear, 8-pound, 6-ounce, newborn infant Jesus, don’t even know a word yet, just a little infant and so cuddly, but still omnipotent . . . .”

Obviously that’s completely overblown and played for laughs, and seems calculated to offend. As one hostile review of the movie says: “[I]t is clear that [Ricky Bobby], his family and his best friend, Cal, don’t know much about Jesus or His teachings. Their Christian faith is completely mindless and self-serving.”[15] Nonetheless, it drives home the point that we cannot hear Jesus’ words, we cannot “listen to him,” when we conceive of him only through our own preferences and inclinations as embodying nothing more than our own likes and dislikes.

This is no different from Jefferson hacking away at the New Testament; Jesus as “8-pound, 6-ounce, newborn infant . . . [although] still omnipotent” (or whatever our preferred, self-made image may be) is no more to be taken seriously than is Jesus the moral philosopher.

The other way we don’t listen to Jesus takes his divinity and authority seriously, but not his actual words. More often than not this sort of not listening takes the form of talking over Jesus or of putting words into his mouth. The “poster child” for this sort of not listening is Archie Bunker, the pater familias from the old television show All in the Family.[16] If you recall the show, you will remember any number of scenes in which Archie respond to a situation by saying, “As the Good Book says . . . .” and then offer some mangled word of wisdom that was like nothing ever written in Scripture. Among my favorite religious Bunkerisms were “Let the one without sin become a rolling stone” and “Patience is a virgin.”

The world is full of Archie Bunkers who will say, “Jesus said this” or “Jesus said that” – who will tell you flat out that Jesus is firmly against abortion (about which he said nothing) or that Jesus doesn’t like gays or lesbians (homosexuality being something else he never mentioned). I occasionally wear a t-shirt that bears a familiar portrait of Jesus under which are the words, “I never said that. (signed) Jesus.” I was wearing it not too long ago when a man said, “I like your shirt.” I answered, “Thank you. Did you actually read it?” He took a closer look, got a sour look on his face, and just walked away. I kind of suspect he might be one of those folks who’s a little like Archie Bunker.

We cannot listen to Jesus when we talk over him. We cannot listen to Jesus when we put words into his mouth. We cannot listen to Jesus when we presume to speak for him. “You can safely assume that you’ve created God in your own image when it turns out that God hates all the same people you do,” says writer Anne Lamott.[17] I would suggest that one has also created God in one’s own image when it turns out that God thinks the same things one thinks or says the same things one would say. I read a comment on an internet blog recently in which the writer said he grew up in a church where “people would quote the Scriptures, ‘To err is human; to forgive, divine’ or ‘God helps those who help themselves.’” Neither of those shibboleths are actually from scripture. The first is from Alexander Pope, and the second from Benjamin Franklin. Again, like Archie Bunker, we cannot listen to Jesus when we put words into his mouth, when Jesus seems to say the things we would say.

The voice on the Holy Mountain addressed all the Thomas Jeffersons, Ricky Bobbies, and Archie Bunkers among us. God’s first words, “This is my Son, the Beloved,” address the former. This Jesus is not just a good philosopher; this Jesus is not just the little infant of Christmas. This Jesus is, as Peter said, the Son of the Living God, fully human and fully divine. Take him seriously. The “divine plea” with which the voice ends, “Listen to him,” addresses the latter, the Archie Bunkers. Listen to his words and take them seriously.

How can we do that? By reading the Holy Bible, on a regular (and I would suggest daily) basis. By studying it. By knowing it. By knowing Jesus’ words contained in it. If we are to take the divine admonition at all seriously, regular studious reading of Scripture is the only way to do so. If you don’t already, consider taking that on as your Lenten discipline starting this Wednesday.

“This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” This is the Bible; read it!

Let us pray:

Blessed Lord, who caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which you have given us in our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.[18]

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Last Sunday after Epiphany, February 11, 2024, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Mt. Vernon, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest presider and preacher.

The lessons were from the Revised Common Lectionary, Year B, Last Sunday after Epiphany: 2 Kings 2:1-12; Psalm 50:1-6; 2 Corinthians 4:3-6; and St. Mark 9:2-9. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

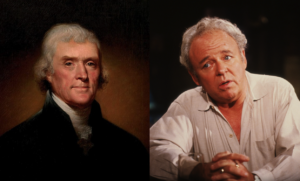

The illustration is a combination of portraits of Thomas Jefferson and Carroll O’Connor, the actor who portrayed Archie Bunker.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Mark 8:29; cf Matthew 16:15 and Luke 9:20

[2] Mark 8:33

[3] Mark 8:34 (NRSV)

[4] John 1:14 (NRSV)

[5] 2 Peter 1:16-17 (NRSV)

[6] Matthew 16:16 (NRSV)

[7] See Kaufmann Kohler and Emil G. Hirsch, Son of God, Jewish Encyclopedia, undated, accessed 20 January 2024

[8] Mark 9:9 (NRSV)

[9] David Lose, The Transfiguration of Peter, Working Preacher, February 27, 2011, accessed 20 January 2024

[10] Warren Carter, Commentary on Matthew 17:1-9, Working Preacher, February 28, 2017, accessed 20 January 2024

[11] Peter Woods, Back AWAY from the Drawing Board!, The Listening Hermit, February 25, 2011, accessed 20 January 2024 (Emphasis in original)

[12] Owen Edwards, How Thomas Jefferson Created His Own Bible, Smithsonian Magazine, January 2012, accessed 20 January 2024

[13] C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (Collins, London:1952), page 54

[14] Talladega Nights: The Legend of Ricky Bobby; directed by Adam McKay; performances by Will Farrell, John C. Reilly, and Sacha Baron Cohen; Columbia Pictures, 2006

[15] Anonymous, Ridiculing the Bible Belt and White Southern Christian Males, MovieGuide: The Family Guide to Movies and Entertainment, undated, accessed 20 January 2024

[16] All in the Family; created by Norman Lear; performances by Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton; Tandem Productions; CBS, 1971-1979

[17] Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird (Anchor Books, New York:1995), page 22

[18] Collect, Proper 28, for the Sunday closest to November 16, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 236

Leave a Reply