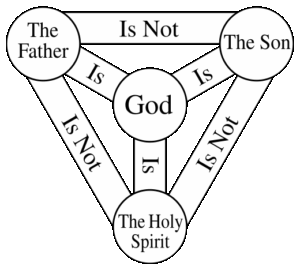

A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

Then the Immigration and Customs Enforcement doubled down on Mr. Trump’s promises of “mass deportations” across the country, but especially in Southern California and particularly in Los Angeles (where I grew up, by the way). People took to the streets in protest; the administration used that as an excuse to nationalize the California National Guard and met the protesters not only with 2,000 guardsmen but with 700 Marines, as well.

One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”

One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”

I understand that St. Andrew’s Parish is, today, beginning its annual stewardship campaign, so I suppose it’s appropriate that we heard the story of Jesus being confronted by the wealthy man who wants to inherit eternal life in today’s Gospel reading from Mark. This tale must have been an important one to the earliest Christians, because we find it in all three of the Synoptic Gospels. Mark tells us only that the man is wealthy; Matthew adds that he is young; and Luke informs us that he is a ruler of some sort. But none of those details really changes the basic nature of the encounter: a potential disciple comes to Jesus seeking guidance and Jesus tells him that he must give up everything he possesses – “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor….”

I understand that St. Andrew’s Parish is, today, beginning its annual stewardship campaign, so I suppose it’s appropriate that we heard the story of Jesus being confronted by the wealthy man who wants to inherit eternal life in today’s Gospel reading from Mark. This tale must have been an important one to the earliest Christians, because we find it in all three of the Synoptic Gospels. Mark tells us only that the man is wealthy; Matthew adds that he is young; and Luke informs us that he is a ruler of some sort. But none of those details really changes the basic nature of the encounter: a potential disciple comes to Jesus seeking guidance and Jesus tells him that he must give up everything he possesses – “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor….” “They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats.”

“They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats.” Again this week as last, our first reading today is from the First Book of Kings and like last week’s, it is a prayer spoken by King Solomon. Last week, it was a private prayer spoken in a dream late at night. Today, it is a public prayer. As long as it was, this reading is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that Solomon offered when the Temple was finished and consecrated. In it, Solomon asks an important question, “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?”

Again this week as last, our first reading today is from the First Book of Kings and like last week’s, it is a prayer spoken by King Solomon. Last week, it was a private prayer spoken in a dream late at night. Today, it is a public prayer. As long as it was, this reading is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that Solomon offered when the Temple was finished and consecrated. In it, Solomon asks an important question, “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?” The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.”

The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.” We have had more than enough of contempt,

We have had more than enough of contempt, Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter.

Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter. In the Episcopal Church, when we baptize a person, we pray that God will “give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will, and to persevere, a spirit to know, and love, [God], and the gift of joy, and wonder in all [God’s] works.”

In the Episcopal Church, when we baptize a person, we pray that God will “give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will, and to persevere, a spirit to know, and love, [God], and the gift of joy, and wonder in all [God’s] works.”