On April 12, a little more than seven months ago, I was privileged to officiate and preach at a service of Choral Evensong at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland. Following the service, on our way home to Medina, my wife Evelyn and I stopped at a Lebanese restaurant in Middleburg Heights for a late dinner in celebration of our 43rd wedding anniversary, which that day was. After a lovely meal of hummus, baba ganoush, spicy beef kafta, and chicken shwarma, we went home to bed. A few hours later, around 2 a.m., I woke up with a horrendous case of heartburn. I took some antacid and went back to sleep sitting up in my favorite armchair. At 7 a.m. the next morning, I woke up knowing that I hadn’t had indigestion after all; I was having a heart attack.

On April 12, a little more than seven months ago, I was privileged to officiate and preach at a service of Choral Evensong at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland. Following the service, on our way home to Medina, my wife Evelyn and I stopped at a Lebanese restaurant in Middleburg Heights for a late dinner in celebration of our 43rd wedding anniversary, which that day was. After a lovely meal of hummus, baba ganoush, spicy beef kafta, and chicken shwarma, we went home to bed. A few hours later, around 2 a.m., I woke up with a horrendous case of heartburn. I took some antacid and went back to sleep sitting up in my favorite armchair. At 7 a.m. the next morning, I woke up knowing that I hadn’t had indigestion after all; I was having a heart attack.

Tag: Psalms (Page 3 of 9)

John, your parish secretary, puts together a mailing every week that he sends to the clergy who will be joining you as presiders and preachers. He includes in that mailing some of the material from an Augsburg Fortress publication called “Sundays and Seasons,” which is a great lectionary resource. The illuminations that your lectors read before each Bible reading giving a little introduction about the lesson come from “Sundays and Seasons.” I’ve been familiar with the publication for a long time, though I’ve never been a subscriber: I used to participate in a weekly ecumenical lectionary study group that included Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, and Episcopal clergy and our Lutheran colleagues often brought something from “Sundays and Seasons” into our discussions.

John, your parish secretary, puts together a mailing every week that he sends to the clergy who will be joining you as presiders and preachers. He includes in that mailing some of the material from an Augsburg Fortress publication called “Sundays and Seasons,” which is a great lectionary resource. The illuminations that your lectors read before each Bible reading giving a little introduction about the lesson come from “Sundays and Seasons.” I’ve been familiar with the publication for a long time, though I’ve never been a subscriber: I used to participate in a weekly ecumenical lectionary study group that included Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, and Episcopal clergy and our Lutheran colleagues often brought something from “Sundays and Seasons” into our discussions.

This week “Sundays and Seasons” offered this précis as an introduction to our gospel reading, which is Matthew’s Parable of the Talents:

Jesus tells a parable about his second coming, indicating that it is not sufficient merely to maintain things as they are. Those who await his return should make good use of the gifts that God has provided them.[1]

It’s now that time of year when clergy and church councils like to talk about stewardship of God’s gifts, and I am sure that you have heard many sermons that take exactly this approach to the Parable of the Talents;. I know that I have both heard and preached such sermons! But, having taken a closer look at the text recently, I that interpretation misses the mark. I don’t think this is a story about stewardship, at all: I believe it’s a story about conscience or, rather, the lack of conscience.

We have three intriguing lessons from scripture today. First we have a denunciation of Hebrew worship, which also interestingly contains a verse most famous in American politics for having been spoken on the steps of the Lincoln monument by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Some people who dislike liturgy, or some aspect of liturgy, like incense, or vestments or music, ignoring that sentence about justice flowing like streams, have used this text to prove that God also dislikes, liturgy, or incense, or vestments, or whatever. However, that’s not what this lesson is about and I’ll get back to that in just a moment.

We have three intriguing lessons from scripture today. First we have a denunciation of Hebrew worship, which also interestingly contains a verse most famous in American politics for having been spoken on the steps of the Lincoln monument by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Some people who dislike liturgy, or some aspect of liturgy, like incense, or vestments or music, ignoring that sentence about justice flowing like streams, have used this text to prove that God also dislikes, liturgy, or incense, or vestments, or whatever. However, that’s not what this lesson is about and I’ll get back to that in just a moment.

The second lesson is a crazy excerpt from Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians. With all that talk of God playing a trumpet and people flying up to meet Jesus in the air, it reads like some sort of hallucination or LSD trip, or like the ramblings of our crazy uncle who shows up for Thanksgiving dinner, muttering about things people don’t understand. The thing about Paul’s letters, though, is that they’re intended to be read as a whole. Breaking them up into excerpts, as the common lectionary does, can lead to a misreading and a misunderstanding. Fortunately, the lectionary doesn’t intend the epistle lesson to necessarily be read and interpreted in conjunction with the gospel lesson, as it does with the thematically related Old Testament lesson, so today we’ll just set crazy, old uncle Paul in a chair over there and let him be today.

Finally, from Matthew’s gospel, we have a lesson in which Jesus teaches about the kingdom of heaven. He does this using a parable. Now, you know what a parable is, right? It’s kind of like a metaphor and it’s kind of like a simile, but it’s neither a metaphor nor a simile. In a metaphor, the speaker says or implies that A is B, when the listener knows darn good and well that A is not B at all, but metaphoric imagery challenges us to consider A in ways we might not have done before.

What does it mean to say “Jesus is Lord”? The question arises because of today’s dialog between Jesus and some of the Pharisees about the relative importance of the Commandments. Jesus responds to a lawyer’s question about the greatest commandment and then follows his response with a question about the lordship of the Messiah, the anticipated “Son of David.”

What does it mean to say “Jesus is Lord”? The question arises because of today’s dialog between Jesus and some of the Pharisees about the relative importance of the Commandments. Jesus responds to a lawyer’s question about the greatest commandment and then follows his response with a question about the lordship of the Messiah, the anticipated “Son of David.”

Jesus very rarely claimed this title for himself and when he did it was generally in the sort of oblique way we see in today’s exchange. He doesn’t come right out and say “I am the Lord,” but he hints at it. Usually, however, it is applied to him by others. In daily usage among First Century Jews, addressing someone as “Lord,” was probably meant as an honorific synonymous with “Rabbi,” “Teacher,” “Master,” and so forth, the way we might use “Doctor,” “Professor,” or address a judge as “Your Honor.”

“The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”

“The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”

This is an ugly parable that Matthew reports in today’s gospel. It is similar to a parable that is related in Luke’s gospel, but Matthew adds details that challenge us deeply, even to the core of our faith, to the center of our being as Christians. When Luke tells the story, the host inviting his neighbors to dinner is not a king; he’s just “someone.”[1] When Luke’s host sends his servant to tell the intended guests that all is ready, they offer only excuses; no one “makes light” of the occasion and no one seizes, mistreats, or kills the slaves as happens in the Matthean version.[2] Luke’s host gets angry, but only Matthew’s king sends an army “destroy the murderers and burn their city.”[3] Both hosts send the slaves back out to invite others from the streets and highways; Luke’s dinner host adds an instruction specifically to invite “the poor, the crippled, the blind, and the lame.”[4] In both stories the banquet hall is filled, but only in Matthew’s story is there the judgment, not mentioned in Luke’s, that the substitute guests include “both good and bad.”[5] And, finally, Matthew’s Jesus adds the detail about the man present without the proper wedding garment who is thrown into the “outer darkness” and that final warning, “Many are called, but few are chosen.”[6]

This is the second of three Sundays during which our lessons from the Gospel according to Matthew tell the story of an encounter between Jesus and the temple authorities. Jesus has come into Jerusalem, entered the Temple and had a somewhat violent confrontation with “the money changers and … those who sold doves,”[1] gone back to Bethany, and then returned to the Temple the next day. In last week’s lesson, “the chief priests and the elders of the people” demanded that he explain himself, asking, “By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority?”[2] In good rabbinic fashion, Jesus answers their question with a question and, when they cannot answer his question, he declines to answer theirs.

This is the second of three Sundays during which our lessons from the Gospel according to Matthew tell the story of an encounter between Jesus and the temple authorities. Jesus has come into Jerusalem, entered the Temple and had a somewhat violent confrontation with “the money changers and … those who sold doves,”[1] gone back to Bethany, and then returned to the Temple the next day. In last week’s lesson, “the chief priests and the elders of the people” demanded that he explain himself, asking, “By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority?”[2] In good rabbinic fashion, Jesus answers their question with a question and, when they cannot answer his question, he declines to answer theirs.

But, Jesus being Jesus, he doesn’t leave it at that: he goes on to tell three parables. First, a story about two sons, one of whom refuses to do as his father instructs but later changes his mind and obeys, the other of whom agrees to do as he is told but then fails to do so. The second, today’s story about a vineyard. And the third, a story about a wedding feast where the invited guests decline attendance so passers-by are dragged in off the streets, but one man (who fails to wear an appropriate wedding garment) is tossed back out into a place of perdition. We heard the first last week; we’ll hear the third next week. Today, we have heard “the Parable of the Wicked Tenants.”

Power and authority. These are the subjects of our lessons from Scripture this morning. Later this month they will figure as key concepts in a trial scheduled to begin in Fulton County, Georgia. That trial will focus on an alleged attempt to disrupt, even to stop, what we have come to call “the peaceful transfer of power.” Historian Maureen MacDonald wrote a few years ago:

Power and authority. These are the subjects of our lessons from Scripture this morning. Later this month they will figure as key concepts in a trial scheduled to begin in Fulton County, Georgia. That trial will focus on an alleged attempt to disrupt, even to stop, what we have come to call “the peaceful transfer of power.” Historian Maureen MacDonald wrote a few years ago:

The swearing-in ceremony allows for the peaceful transfer of power from one President to another. It formally gives the “power of the people” to the person who has been chosen to lead the United States. This oath makes an ordinary citizen a President.[1]

In Paul’s letter to the Philippians, part of which we heard this morning, the apostle writes about the power of Jesus Christ by quoting a liturgical hymn sung in early Christian communities:

At the name of Jesus?every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord.[2]

Heavenly Father,

Heavenly Father,

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered.

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who hast by Thy might,

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Amen.[1]

Last week, Evelyn and I were in Topeka, Kansas, visiting our son and his family. On Friday afternoon we were at loose ends while the grandkids were at school and their parents were at work, so we decided to visit the Brown vs. Board of Education National Monument. This memorial is a small museum in what was the segregated, all-black Monroe Elementary School south of Topeka’s downtown. I’m glad we went to see it. It is a remarkable place, and a fascinating if sobering reminder of how bad racism has been in this country and how much further we still have to go to remove that stain from our nation.

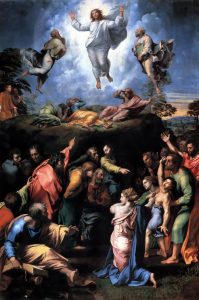

Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,”[1] the Feast of the Transfiguration.

Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,”[1] the Feast of the Transfiguration.

The church’s understanding of the meaning of the event described by Luke in today’s gospel lesson is summarized in today’s opening collect: “[O]n the holy mount [God] revealed to chosen witnesses [God’s] well-beloved Son, wonderfully transfigured, in raiment white and glistening.” The collect expresses the church’s hope that Christians “may by faith behold the King in his beauty.”[2] The Collect for the Last Sunday after Epiphany, on which we also read about this event, similarly summarizes the event as the revelation of the Son’s “glory upon the holy mountain,” and expresses the hope that the faithful may be “changed into his likeness from glory to glory.”[3]

In other words, the Transfiguration is all about Jesus, but, while that’s true, nothing about Jesus is ever all about Jesus! It’s about Jesus to whose pattern his followers are to be conformed,[4] so it is about us, as well. And, as any story is about not only its protagonist but also about the “bit players” who surround him, it is about James and John and Peter, who represent us.

When I was a sophomore in college, I lived in a dormitory suite with nine other guys: six bedrooms, two sitting rooms, and a large locker-room style bathroom. About mid-way through the first semester, one of our number, a 3rd-year biochemistry major, suggested that set up a small brewery in one of the sitting rooms. We all read up on how to make beer and thought it was a great idea; so we helped him do it. It takes three to four weeks to make a batch of beer, so over the next few months we made quite a bit of beer.

When I was a sophomore in college, I lived in a dormitory suite with nine other guys: six bedrooms, two sitting rooms, and a large locker-room style bathroom. About mid-way through the first semester, one of our number, a 3rd-year biochemistry major, suggested that set up a small brewery in one of the sitting rooms. We all read up on how to make beer and thought it was a great idea; so we helped him do it. It takes three to four weeks to make a batch of beer, so over the next few months we made quite a bit of beer.

Then, late in the spring semester, one of our roommates had a chance to get some yeast from a famous California champagne producer, so we thought we’d use it in our beer. We thought we’d be super-cool making beer with champagne yeast and our beer would be magnificent; we weren’t and it wasn’t. In fact, it was downright awful.

It turns out that not all yeasts are the same!