On April 12, a little more than seven months ago, I was privileged to officiate and preach at a service of Choral Evensong at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland. Following the service, on our way home to Medina, my wife Evelyn and I stopped at a Lebanese restaurant in Middleburg Heights for a late dinner in celebration of our 43rd wedding anniversary, which that day was. After a lovely meal of hummus, baba ganoush, spicy beef kafta, and chicken shwarma, we went home to bed. A few hours later, around 2 a.m., I woke up with a horrendous case of heartburn. I took some antacid and went back to sleep sitting up in my favorite armchair. At 7 a.m. the next morning, I woke up knowing that I hadn’t had indigestion after all; I was having a heart attack.

On April 12, a little more than seven months ago, I was privileged to officiate and preach at a service of Choral Evensong at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland. Following the service, on our way home to Medina, my wife Evelyn and I stopped at a Lebanese restaurant in Middleburg Heights for a late dinner in celebration of our 43rd wedding anniversary, which that day was. After a lovely meal of hummus, baba ganoush, spicy beef kafta, and chicken shwarma, we went home to bed. A few hours later, around 2 a.m., I woke up with a horrendous case of heartburn. I took some antacid and went back to sleep sitting up in my favorite armchair. At 7 a.m. the next morning, I woke up knowing that I hadn’t had indigestion after all; I was having a heart attack.

I spent the next 24 hours in one hospital hooked up to various monitors and having blood drawn every hour while they confirmed that that’s what it was, then I was sent to another hospital where they put me on an x-ray table, stuck in catheter in an artery in my leg, threaded it up to my heart, and discovered three blocked coronary arteries. I lay on that x-ray table for 45 minutes while two cardiologists argued about whether or not to crack my chest and do a by-pass. I count myself fortunate that they decided, instead, to try balloon angioplasty, which worked, and that I now have three stents rather than a bunch of arterial graphs and a zipper scar in the middle of my chest. But…

I would not be unwilling to describe the 48 hours during which all of that happened as a time when the sun darkened, the moon gave no light, the stars fell, and the heavens were shaken.[1] They were a couple of scary days, characterized by pain and uncertainty and filled with events for which my wife and I may have thought we were prepared, but clearly weren’t, days which make me wonder if Jesus in our gospel lesson isn’t talking about something more immediate and personal than some distant future “Second Coming.”

This section of Mark’s Gospel is referred to as “the little apocalypse.” The word apocalypse is often used as a synonym for “the end of the world” or to refer to a disastrous event or catastrophe, but those meanings are secondary. Apocalypse is a Greek word. Usually translated as “revelation,” its actual meaning is the “detaching or pulling back of a cover.” Apocalypses are kind of like epiphanies: David Dark, author of the book Everyday Apocalypses insists that they are epiphanies which announce “a new world of unrealized possibility” and “invest the details of the everyday with cosmic significance.”[2] Epiphanies, however, are usually welcome and described in positive terms: a flash of brilliance, a ray of light, the turning on of a lamp or a lightbulb, the parting of clouds. Apocalypses, on the other hand, are described cataclysmically: “it was a bolt of lightning out of the blue,” “my head exploded,” “it blew my mind,” “it hit me like a ton of bricks,” “it is a day of darkness and deep gloom.” Thus, we get that secondary, catastrophic, end-of-the-world understanding.

But notice, writes David Lose, who used to be president of Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia,

. . . that there is no mention in [today’s gospel lesson] of the end of the world, no indication of final judgment, no call to flee the day-to-day realities and obligations and responsibilities of life, only the promise that “he (the Son of Man) is near”. Indeed, if we recognize that the key temporal markers of the parable that concludes this passage – evening, midnight, cockcrow, and dawn – as identical to the temporal markers of the passion story about to commence . . . then we realize that much if not all of what comes before – darkening of the sun, the powers being shaken, etc. – also correspond with key elements of the passion narrative. Mark, in other words, isn’t pointing us to a future apocalypse . . . but rather a present one, as Christ’s death and resurrection change absolutely everything. For once Jesus suffers all that the world and empire and death have to throw at him – and is raised to new life! – then nothing will ever be the same again. Including our present lives and situations.[3]

Advent, the first season of the church year which begins today, is a time of preparation, preparation for the celebration of Christ’s first coming, his birth in Bethlehem of Judea 2,000 years ago, but also preparation for his return. So our lectionary treats us to a mixed bag of passages from Scripture. We get lessons about the events leading up to the first Christmas: the Annunciation and the story of John the Baptist. We get prophecies that Christians associate with the coming of the Messiah, such as next week’s passage from Isaiah with the words “Comfort, comfort ye, my people.”[4] We get other prophecies which seem to be about a rather more cataclysmic appearance of God, such as today’s Old Testament lesson. And we get passages like today’s gospel lesson which many read as a prediction of the so-called “end times,” but which others, like Professor Lose, read as addressing the present.

The study of the end times is called eschatology from another Greek word (Christianity is full of Greek words). In this case, the word is eschaton meaning “last things,” commonly understood to refer to the end of time. One school of eschatological thought is called “realized” or “fulfilled” eschatology, which argues that all of the things in the New Testament that look like predictions of the future have already happened, or are constantly taking place in a believer’s everyday life. In the words of C.H. Dodd, one of its earliest proponents, this view “dislocates” the eschaton moving it “from the future to the present, from the sphere of expectation into that of realized experience.”[5]

Now, I’m not sure I entirely buy into all the notions of realized eschatology. I believe whole-heartedly that, as we say in the Nicene Creed, the Son of God “will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead”[6] and that history will not extend into an endless future but will culminate in an eternal now.[7] But I also believe that Jesus wasn’t kidding when the last thing he said to the disciples in Matthew’s gospel was, “Remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”[8] So, I suggest that the concept of a realized eschaton offers a valuable point of view.

For example, although the word eschaton is usually understood temporally, it has a broader meaning: it “can be construed [to refer to] purposes or final realities, in the sense of ‘those things which possess finality and ultimacy of meaning’.”[9] Read from this perspective, biblical readings like today’s gospel “encourage [us] to treat every moment as of final importance, to recognize that it is in this moment that [we have] the opportunity . . . to participate in the life of God.”[10]

With its mixed bag of lessons, the season of Advent embodies the sometimes apparently contradictory both/and reality of the Christian faith: our insistence that death is conquered although people still die, that sin is forgiven although people still trespass, that Christ is present although we do not see him, that the victory is already won although the battle continues. This is a season in which we both celebrate the past as we remember Jesus’ humble birth 2000 years ago and get ready for the future anticipating Christ’s glorious return, but we do so by focusing on the present with admonitions to keep alert, to be prepared, and to stay vigilant in our everyday, realized experience, because the unexpected can happen at any time – “in the evening, or at midnight, or at cockcrow, or at dawn.”[11]

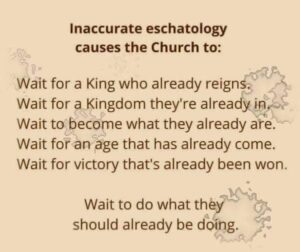

Fr. Ken Saunders, the rector of St. James Episcopal Church in Greeneville, Tennessee, recently posted a meme on Facebook which reads: “Inaccurate eschatology [by which I believe he means one that focuses only on the end of the world] causes the Church to wait for a King who already reigns, wait for a Kingdom they’re already in, wait to become what they already are, wait for an age that has already come, wait for victory that’s already been won, [and] wait to do what they should already be doing.”[12]

That last bit about not doing what we should be doing is true not only of the church as an institution, but of all of us as individuals. If you stop to think about it, and Advent is a really good time to do so, there is probably something that each of us needs to be doing but isn’t. And there are probably all sorts of signs of that need in our lives. “Learn the lesson of the fig tree,” says Jesus.[13] Those signs may be as simple, and as small and sometimes unnoticed, as the bud of a leaf on a tree in spring. Simple and small as they may be, look for them. For when you see them, Christ is “near, at the very gates;”[14] not just coming, but already arrived. Keep alert for those everyday apocalypses that are drawing back the curtain obscuring both your need to be doing things and the presence of the Lord in your life.

That’s what my heart attack was; it pulled back the cover from a lot of stuff that I should have been doing about my health, but wasn’t. Since it happened, I’ve started doing them: I go to the gym; I walk five miles a day; I’ve changed my diet; and I’ve lost nearly sixty pounds. I’m physically healthier than I’ve been in decades, and that has enhanced my prayer life. I can personally attest that, as author Suzanne Guthrie writes, “Cataclysm dims the safe filters of ordinary sight to heighten [one’s] view of Reality. Shock, fear, grief, courage, and then, perhaps, curiosity, open the door to the mystical life. Once you pass through the threshold of doom, ultimately, you’ll awake to the beauty of holiness.”[15] As David Dark observed, “[H]ope has nowhere else to happen but the valley of the shadow of death.”[16] It is in the midst of our everyday apocalypses that the Lord restores us, shows us the light of his countenance, and saves us.[17]

This Advent as you focus on the past and the future, getting ready to celebrate Christ’s humble birth in the first Christmas and preparing for his Second Coming in glory, keep awake and watch for the everyday apocalypses happening in your present, remembering Christ’s promise: “I am with you always.”[18] Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the First Sunday of Advent, December 3, 2023, to the people of Trinity Lutheran Church, Clinton, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest presider and preacher.

The lessons were from the Revised Common Lectionary, Year B, Advent 1: Isaiah 64:1-9; 1 Corinthians 1:3-9; Psalm 80:1-7, 16-18; and St. Mark 13:24-37. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

The illustration is an internet meme posted on Facebook by the Rev. Ken Saunders of St. James Episcopal Church, Greeneville, TN, on November 22, 2023.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Mark 13:24-25

[2] David Dark, Everyday Apocalypse: The Sacred Revealed in Radiohead, The Simpsons, and Other Pop Culture Icons (Baker Publishing, Grand Rapids, MI:2002), page 12

[3] David J. Lose, Advent 1B: A Present-Tense Advent, … in the Meantime, November 27, 2017, accessed 29 November 2023

[4] Isaiah 40:1-11

[5] C. H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom (Nisbet, London:1936), page 50

[6] The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 359

[7] See Paul Tillich, The Eternal Now (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York:1963)

[8] Matthew 28:20 (NRSV)

[9] Mikel Burley, Dislocating the Eschaton? Appraising Realized Eschatology, Sophia 56 (14 May 2016), pp. 435 – 52, quoting G. E. Ladd, The Presence of the Future: The Eschatology of Biblical Realism (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids:1974), p. 17, accessed 25 November 2023

[10] Ibid.

[11] Mark 13:35 (NRSV)

[12] Ken Saunders, posted on Facebook November 22, 2023

[13] Mark 13:28

[14] Mark 13:30 (NRSV)

[15] Suzanne Guthrie, Watching and Longing, At the Edge of the Enclosure, undated, accessed 28 November 2023

[16] Dark, op. cit., pages 10-11

[17] Psalm 80:3

[18] Matthew 28:20 (NRSV)

Leave a Reply