====================

A sermon offered on Twenty-Second Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 25B, Track 1, RCL), October 25, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Job 42:1-6,10-17, Psalm 34:1-8, Hebrews 7:23-28; and Mark 10:46-52. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page. The collect for the day, referenced in the sermon, is found at the same site.)

====================

Last week, I gave away the ending of Job. I told you that everything turned out all right in the end, and so it has. Job has repented, not of any sin that warranted his suffering, but of the pride and arrogance (and ignorance) he displayed during his suffering by demanding to confront God. God has forgiven him and to make up for all his loss, his fortunes have been restored many times over. Happy ending! Except not quite . . .

Last week, I gave away the ending of Job. I told you that everything turned out all right in the end, and so it has. Job has repented, not of any sin that warranted his suffering, but of the pride and arrogance (and ignorance) he displayed during his suffering by demanding to confront God. God has forgiven him and to make up for all his loss, his fortunes have been restored many times over. Happy ending! Except not quite . . .

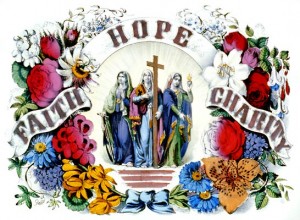

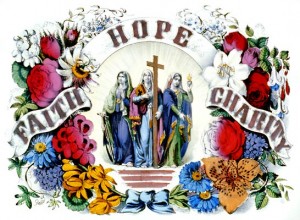

I’ll come back to Job in a minute, but first I want to look at a petition in today’s opening collect and then at the gospel story. The petition is this: “Increase in us the gifts of faith, hope, and charity.” The gospel story is the restoration of sight to blind Bartimaeus to whom Jesus says, “Your faith has made you well.”

What is “faith,” the first of the theological virtues our prayer asks of God and the active agent in healing Bartimaeus? The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews tells us that “faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” (Heb 11:1) Faith is sometimes equated with belief, and in an ancient way that is true but in the modern sense of the word “belief,” that is a misleading equation.

In contemporary English, “belief” is understood to be an opinion or judgment of which the believer is fully persuaded, or alternatively it is considered intellectual assent to a factual assertion. By some it is derided as a false alternative to scientific certainty: one is said to believe that which cannot be proven, but to know that which is made evident by factual data. That’s a false dichotomy, but not one I want to debate this morning. For the moment, let’s accept the notion that belief is assent to an opinion, judgment, or assertion. This may be the first step of faith for, as Paul reminds us in the Letter to the Romans, “faith comes from what is heard,” (Rom 10:17a), through acceptance of assertions. However, faith must be more than that.

In the Epistle of James, we are reminded that such faith, faith which consists only of belief, “by itself, if it has no works, is dead,” (Jm 2:17) and Paul would seem to agree with that when, in his letter to the Galatians, he writes that “the only thing that counts is faith working through love.” (Gal 5:6b, emphasis added)

So, then, faith is not simply the same as belief (as belief is currently understood). Faith is belief plus action. This is in accord with the New Testament understanding of faith; remember that our New Testament was written in Greek and the word we translate as “faith” is pistis, a verb. From a New Testament perspective, faith is not a noun, an object or substance which one has; faith is a verb, an action which one does. But is it more? Is there another element of faith.

I suggest to you that there is and we find that element in the original meaning of the word “belief.” Our word “belief” derives from the same root as our word “beloved,” and in original meaning as more the sense of “confidence” or “trust” than of intellectual assent. It means to give one’s heart to the object of one’s belief.

Faith then is belief plus action plus confidence, and it was faith such as this which led blind Bartimaeus to throw off his cloak and cry out to Jesus, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” Even when those around him would silence him, this faith made him yell even more loudly. This is the faith which our opening prayer asks God to increase in us: not our assurance of the rectitude of some factual assertion made (for example) in the Nicene Creed, but that belief given shape in action and that action undertaken with confidence, and confidence (the Letter to the Hebrews tells us) belongs to hope (Heb 3:6), which is the second theological virtue in our petition to God this morning.

Did you know that we have iconic depictions of the theological virtues in our stained glass windows? Look to the back of the church over the entrance doors. Below the circular rose window are the figures of three women. One holds a cross; one, an anchor; and one, loaves of bread. The figure with the cross is the depiction of Faith. Next to her is the figure holding the anchor of Hope. Which brings us back to Job.

We are, as I mentioned earlier, at the end of the story and everything has turned out all right. Job confesses that he has been arrogant and prideful in demanding a hearing before God; he is healed of his loathsome sores, reconciled to God, and rewarded with an abundance of wealth and family and comfort.

Once again, however, the lectionary leaves something out. Between verse 6, the end of his confession, and verse 10, which begins the description of his reward, God addresses Job’s three friends, Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite. God says, “My wrath is kindled against you . . . ; for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has.” (v. 7)

What is the difference between Job and these other three? The answer is, “Hope.” Throughout his ordeal, despite his pride, despite his arrogant demand that God present himself, despite his denials of any sin, Job has steadfastly maintained his hope in the justice of God. His friends have counseled him to admit to wrongdoing that even they are not sure he has done; they have advised him to just give up. They have given up hope, but Job has not.

What is “hope”? Well, that’s a good question. St. Paul wrote a lot about hope in his various letters, but he never really defines it. He comes closest to doing so in the Letter to Romans in which he writes: “[S]uffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us.” (Rm 5:3-5) And then later in the same letter he says, “In hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.” (Rm 8:24-25)

Theologically, hope is the “virtue by which we desire the kingdom of heaven and eternal life as our happiness, placing our trust in Christ’s promises and relying not on our own strength, but on the help of the grace of the Holy Spirit.” (C.C.C., 2nd Ed., 1997, Para. 1817)

Hope is not optimism. Optimism claims everything will be good despite all evidence of reality to the contrary; pessimism denies even the possibility of good because of present evidence. The nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer said, “The optimist thinks this is the best of all possible worlds. The pessimist fears it is true.”

Optimism can be defeated by reality. Pessimism revels in reality but defeats itself. Hope, like optimism, expects the good. Hope, like pessimism, accepts reality. Hope does not deny the poverty of spirit that underlies fear, the sinfulness that underlies all tragedy, and the evil that causes systemic inertia. Hope, however, has a trump card – the capacity of the human heart. When reality grinds optimism down and reduces pessimism to a self-defeating smugness, hope will go toe-to-toe with reality because the heart’s capacity to love refuses to quit. This is why the letter to the Hebrews describes hope as “a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul” (Heb 6:19) and why the iconic figure of Hope holds an anchor.

This is the steadfastness that our opening prayer seeks from God.

The last of the theological virtues for which we have prayed is Charity, who is depicted in our window as a woman distributing bread to hungry children. Theologically, Charity is the “virtue by which we love God above all things for his own sake, and our neighbor as ourselves for the love of God.” (C.C.C., Para. 1822) Interestingly, though, we almost never read of charity in our English language bibles. In the New Revised Standard Version, the word “charity” appears only five times and four of those are in the Apocrypha; in the canonical scriptures, the word appears only in the book of Acts. In the Authorized or “King James” version it appears 24 times, more than a third of those in one book, St. Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians from which you will (I’m sure) recognize these words:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing. And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. Charity never faileth . . . . (1 Cor 13:108a)

In our modern translation we have changed the word “charity” to “love” and that bit of First Corinthians has become very popular at weddings, but it’s not about romantic love at all. It is about something much different. You know (you’ve heard it here before!) that the word in the original Greek is agape, which refers to selfless love. This is the love that one extends to all people, whether family members or distant strangers; it is the according of human dignity to everyone, simply because they are human. Agape was translated by St Jerome into the Latin word caritas, which is the origin of our word “charity.” C.S. Lewis referred to it as “gift love” and described it as the highest form of Christian love. But it is not solely a Christian concept; it appears in other religious traditions, such as the idea of metta or “universal loving kindness” in Buddhism.

Charity, agape, is not simply love generated by an impulse emotion. Instead, charity, agape, is an exercise of the will, a deliberate choice. This is why Jesus can command us to love one another as he loves us, to love our neighbors, even our enemies, as ourselves. God is not commanding us to have a good feeling for these others, but to act in charity, in “gift love,” in self-giving agape toward them. Charity, agape, is matter of commitment and obedience, not of feeling or emotion. When Paul admonishes Christians in the Letter to the Ephesians to “live in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us,” offering himself (as our reading from Hebrews says) “once for all,” it is precisely this kind of self-sacrificing love, Charity, agape, to which we are called.

When the Resurrected Jesus asks Peter, “Do you love me?” three times, the first two times the word is agape. “Peter,” Jesus is asking, “are you willing to do things for my sake that you do not want to do?” This is the sort of love, of Charity, that is depicted in our third iconic window, the woman giving bread to poor and hungry children, love which leads us to give sacrificially.

The contemporary hymn writer John Bell, a Scotsman affiliated with the Iona Community, has written a beautiful song entitled The Summons which I wish I had the voice to sing to you. I don’t, so you don’t want me to sing it, but please listen as I read the lyrics. I believe these words perfectly describe the sort of Charity our opening prayer asks God to increase in us:

Will you come and follow me

If I but call your name?

Will you go where you don’t know

And never be the same?

Will you let my love be shown,

Will you let my name be known,

Will you let my life be grown

In you and you in me?

Will you leave yourself behind

If I but call your name?

Will you care for cruel and kind

And never be the same?

Will you risk the hostile stare

Should your life attract or scare?

Will you let me answer pray’r

In you and you in me?

Will you let the blinded see

If I but call your name?

Will you set the pris’ners free

And never be the same?

Will you kiss the leper clean,

And do such as this unseen,

And admit to what I mean

In you and you in me?

Will you love the ‘you’ you hide

If I but call your name?

Will you quell the fear inside

And never be the same?

Will you use the faith you’ve found

To reshape the world around,

Through my sight and touch and sound

In you and you in me?

Lord, your summons echoes true

When you but call my name.

Let me turn and follow you

And never be the same.

In your company I’ll go

Where your love and footsteps show.

Thus I’ll move and live and grow

In you and you in me.

We have prayed this morning that God will increase in us the gift of faith – faith like Bartimaeus’s, belief given shape by action undertaken in confidence which is sustained by hope. We have prayed this morning that God will increase in us the gift of hope – hope like Job’s, the sure and steadfast anchor of the soul not crushed by the suffering of the present sustained by the heart’s capacity to love and the assurance that in end all will make sense. And we have prayed this morning that God will increase in us the gift of charity – the agape love commanded and demonstrated by Christ who gave himself once for all which leads us to give sacrificially.

“And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.” (1 Cor 13:13) May Christ’s charity move and live and grow in us and we in him. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Our Old Testament lesson this morning is a very small bit of the Book of Job, that really sort odd bit of Biblical literature that tells the story of a wager between God and Satan. Some scholars believe that it may find its origins in an earlier Babylonian work known as the Poem of the Righteous Sufferer, that the Jews in Exile became familiar with the older Babylonian story and adapted it to their own theology.

Our Old Testament lesson this morning is a very small bit of the Book of Job, that really sort odd bit of Biblical literature that tells the story of a wager between God and Satan. Some scholars believe that it may find its origins in an earlier Babylonian work known as the Poem of the Righteous Sufferer, that the Jews in Exile became familiar with the older Babylonian story and adapted it to their own theology. Before coming to Ohio, my wife and I lived in the Kansas City metroplex. For reasons that still remain mysterious, I was somehow added to the mailing list for the newspaper of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, which is called The Leaven. When we moved here, I expected that that would stop, but somehow they got my change of address, so I still get The Leaven. I suppose I could have asked to be taken off, but I enjoy reading some of the articles, especially a column written by the paper’s editor-in-chief Father Mark Goldasich. Fr. Goldasich often relates stories of people from around the archdiocese; some are funny, some are touching, and some, like this recently offered story, bring tears to your eyes:

Before coming to Ohio, my wife and I lived in the Kansas City metroplex. For reasons that still remain mysterious, I was somehow added to the mailing list for the newspaper of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, which is called The Leaven. When we moved here, I expected that that would stop, but somehow they got my change of address, so I still get The Leaven. I suppose I could have asked to be taken off, but I enjoy reading some of the articles, especially a column written by the paper’s editor-in-chief Father Mark Goldasich. Fr. Goldasich often relates stories of people from around the archdiocese; some are funny, some are touching, and some, like this recently offered story, bring tears to your eyes: Last week, I gave away the ending of Job. I told you that everything turned out all right in the end, and so it has. Job has repented, not of any sin that warranted his suffering, but of the pride and arrogance (and ignorance) he displayed during his suffering by demanding to confront God. God has forgiven him and to make up for all his loss, his fortunes have been restored many times over. Happy ending! Except not quite . . .

Last week, I gave away the ending of Job. I told you that everything turned out all right in the end, and so it has. Job has repented, not of any sin that warranted his suffering, but of the pride and arrogance (and ignorance) he displayed during his suffering by demanding to confront God. God has forgiven him and to make up for all his loss, his fortunes have been restored many times over. Happy ending! Except not quite . . .  The Book of Common Prayer (1979) lifts these verses and, together with others, uses them in the anthem with which the Burial Office (Rite Two) begins:

The Book of Common Prayer (1979) lifts these verses and, together with others, uses them in the anthem with which the Burial Office (Rite Two) begins: “Each friend,” wrote Anais Nin, “represents a world in us, a world possibly not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.” If a new world is born of merely human friendships, it is certainly true of a friendship with God! When St. Paul wrote to the Corinthian church that “if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new!” he was describing the friendship of God, that friendship which births a new world in us. (2 Cor. 5:17)

“Each friend,” wrote Anais Nin, “represents a world in us, a world possibly not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.” If a new world is born of merely human friendships, it is certainly true of a friendship with God! When St. Paul wrote to the Corinthian church that “if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new!” he was describing the friendship of God, that friendship which births a new world in us. (2 Cor. 5:17) I sometimes wonder to what extent Paul, as an educated Jewish citizen of a Greek-speaking empire, was schooled in the classical Greek philosophers. Had he read Plato’s Republic? Was he aware of the conversation portrayed in Book VII between Socrates and Glaucon in which the allegory of the cave is laid out?

I sometimes wonder to what extent Paul, as an educated Jewish citizen of a Greek-speaking empire, was schooled in the classical Greek philosophers. Had he read Plato’s Republic? Was he aware of the conversation portrayed in Book VII between Socrates and Glaucon in which the allegory of the cave is laid out? We are stepping out of the “common of time,” away from the progression of lessons assigned for the Sundays of Ordinary Time, and instead celebrating the Feast of Michaelmas, known variously as the Feast of Saint Michael the Archangel or as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Raphael, or as the Feast of the Archangels, or as the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels (the latter being the preferred Anglican name for this commemoration). The only reason we are doing so is a personal conceit of your rector; Michaelmas, the 29th of September, just happens to be my birthday. Today I am celebrating the 30th anniversary of my twenty-eleventh birthday. I’ll get back to that in a moment, but first . . . a word about Michaelmas.

We are stepping out of the “common of time,” away from the progression of lessons assigned for the Sundays of Ordinary Time, and instead celebrating the Feast of Michaelmas, known variously as the Feast of Saint Michael the Archangel or as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Raphael, or as the Feast of the Archangels, or as the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels (the latter being the preferred Anglican name for this commemoration). The only reason we are doing so is a personal conceit of your rector; Michaelmas, the 29th of September, just happens to be my birthday. Today I am celebrating the 30th anniversary of my twenty-eleventh birthday. I’ll get back to that in a moment, but first . . . a word about Michaelmas. Today, it is the evening psalm that I ponder.

Today, it is the evening psalm that I ponder. So here we are at the end of the Book of Job and the last of our sermons in this series entitled The Patients of Job. Let’s review the lessons we have learned, the spiritual remedies we have found in the medicine chest of this book.

So here we are at the end of the Book of Job and the last of our sermons in this series entitled The Patients of Job. Let’s review the lessons we have learned, the spiritual remedies we have found in the medicine chest of this book.