====================

This sermon was preached on Sunday, October 7, 2012, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, Proper 22B: Job 1:1; 2:1-10; Psalm 26; Hebrews 1:1-4; 2:5-12; and Mark 10:2-16. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

I know two things today that I didn’t know earlier in the week. First, I know that people read our sign. I got two telephone calls and one email telling me that we had misspelled “patience” on the sign. Second, I know that people won’t believe you when you tell them you did it on purpose. But I really did name this sermon series “The Patients (P-A-T-I-E-N-T-S) of Job” for reasons that I hope will become clear very shortly.

I know two things today that I didn’t know earlier in the week. First, I know that people read our sign. I got two telephone calls and one email telling me that we had misspelled “patience” on the sign. Second, I know that people won’t believe you when you tell them you did it on purpose. But I really did name this sermon series “The Patients (P-A-T-I-E-N-T-S) of Job” for reasons that I hope will become clear very shortly.

Before diving into that subject this morning, however, a word about the Lectionary. For the next four weeks our lessons from the Old Testament will be from the Book of Job as we follow what is called “Track One” of the Revised Common Lectionary.

Track One is a semi-continuous reading of major Old Testament books. The idea this is that we tend to short-change the Old Testament in our Sunday Eucharistic lectionary, and that we need to hear more of the Old Testament and be more familiar with it. So Track One is set up so that we can see the development of some of the great Old Testament stories over the course of successive Sundays; this gives us peculiar opportunities for preaching series like the one we’re embarking on today. The assumption, of course, is that the congregation each Sunday is made up of who actually come to church every week to hear the unfolding of the Old Testament readings in this way. That’s not always a valid assumption. Many of our people, because of work schedules or whatever, do not make it to church every Sunday and so are likely to miss huge chunks of the story. So each week in these sermon there may be a bit of repetition to bring these folks up to speed; I hope weekly congregants will bear with us on that score. (For those of you who may not be here every week, the sermons and lessons will be on the internet for you.)

There other thing about Track One is that, unlike Track Two, which is a Gospel-related track in which the Old Testament reading is selected because it has some sort of thematic connection to the Gospel reading appointed for the day, there is no specific link between the lesson from the Hebrew Scriptures and the lessons from the Christian Scriptures. For example, today we heard part of the backstory of Job’s suffering (we’ll return to that in a moment), while the Gospel focused on Jesus’ teaching about marriage and divorce. I suppose one could draw a connection between the little spat Job and Mrs. Job have at the end of the Old Testament reading and what Jesus has to say, but I’m not going to go there. So for the next few weeks, please don’t expect much exegesis of the Gospel lessons.

So, now, let me answer the signage critics and explain why I chose to (apparently) misuse the word “patients” on our sign. Obviously it is a play on the familiar statement made of a long-suffering individual that he or she has “the patience of Job”. That’s an odd turn of phrase because, as we shall see, Job is not particularly patient; he is at turns angry, demanding, petulant, and sullenly silent, but he is not patient. Nonetheless, I chose to play with and make a pun on that old concept because the story of Job is one to which we can turn are in need of balm for whatever turns in life may beset us.

The great preacher St. John Chrysostom, in a sermon on the Gospel of John, said of Holy Writ,

The divine words, indeed, are a treasury containing every sort of remedy, so that, whether one needs to put down senseless pride, or to quench the fire of concupiscence or to trample on the love of riches, or to despise pain, or to cultivate cheerfulness and acquire patience – in them one may find in abundance the means to do so. (Hom. 37 On John.)

In a sermon on St. Paul’s letter to the Colossians, he likened the Bible to a medicine chest:

Listen, I entreat you, all that are careful for this life, and procure books that will be medicines for the soul . . . . If grief befalls you, dive into [the Holy Scriptures] as into a chest of medicines; take from there comfort for your trouble, be it loss, or death, or bereavement of relations; or rather do not merely dive into them but take them wholly to yourself, keeping them in your mind.” (Hom. IX On Colossians)

This is especially true of the Book of Job.

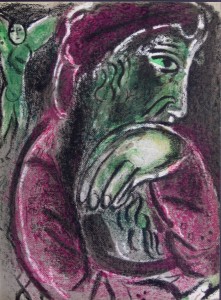

This book, as I made mention from this pulpit some weeks ago, is a work of fiction, but that does not stop it from being a work from which we can learn great truth. Or perhaps I should say “great truths” for, more than any other book in the Bible, Job offers what some might call a “post-modern” or pluraform vision of truth. Job, in the midst of his suffering, is visited by his wife, his friends Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, and a fourth man, Elihu (who may just be a passerby). Each of them offers an explanation of why life has treated Job so shabbily and offers advice as to how he should respond. Job’s answer to each of them is basically, “That may be true for you, but it’s not true for me!” The character Job could be the patron saint of our post-modern age, and the Book of Job offers us a variety of remedies, a selection of alternative truths for whatever besets our spirits; it also provides a glimpse at the over-arching meta-truth that sustains our lives, namely the awesome power of God. We all come to this book, as we come to all of Scripture, as patients seeking medicine for the soul; we are all the “patients of Job.”

When we first open this text we are treated to two scenes involving the characters God and Satan. (I put it that way very advisedly, very carefully. Please always remember that this is a work of fiction and so we have a character named “God” and a character named “Satan” who may or may not behave in the ways the Creator and the Adversary actually interact with the world.) In both of these scenes these two characters make and continue a wager regarding Job. In Chapter 1, all the heavenly court appears before God, including Satan whom God asks where he has been. Satan answers that has been “going to and fro on the earth, and from walking up and down on it.” (1:7) God asks if he has seen God’s servant Job who is a good and righteous man. Satan replies that he has, but then challenges God about Job’s virtue suggesting that Job is only righteous because God has provided him a good life. So they make a wager; Satan bets that if Job loses everything he has, he will curse God. God gives Satan authority to strip him of his wealth and possessions, but forbids him to lay a hand on Job. The next thing we know, Job is struck by calamity after calamity all within a very short time. Four servants come to him, one after another, the next coming before the one before has even finished speaking, telling him that Sabaeans have come and stolen his oxen and donkeys, a fire has destroyed his sheep, Chaldean invaders have killed all his servants, and a collapsing house has killed all his sons and daughters. Job is left with nothing; he tears his clothing, shaves his head, and falls to the ground, but the narrator assures us that “in all this Job did not sin or charge God with wrongdoing.” Rather, he blesses the Name of God! (1:20-21)

Which brings us now to our reading for today and the second scene in the heavenly throne room. Again, the court is assembled; again, Satan is there having come “trom going to and fro on the earth, and from walking up and down on it.” (2:2) Again, God asks if Satan has considered Job; and again, Satan makes a bet with God. It’s all well and good that he’s lost everything, but he’s still alive and healthy; “touch his bone and his flesh,” says Satan, “and he will curse you to your face.” (2:5) “Very well,” says God, “you can cause him illness, but do not take his life.” So Satan “inflict[s] loathsome sores on Job from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head.” (2:7) Job’s response is different from his actions in the first chapter; he engages in no new acts of mourning or worship. Instead, he picks up a piece of broken pot, scratches at his sores, and sits down on a pile of ashes. At this point Mrs. Job (she isn’t given her own name in the text) says to her husband, “Do you still persist in your integrity? Curse God, and die.”

One commentary points out that the concept of integrity in the Old Testament has two prongs. First, it “denotes a person whose conduct is completely in accord with moral and religious norms.” Second, it describes someone “whose character is one of utter honest, without guile.” (The New Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. IV, Abingdon Press: 1996, page 356) Mrs. Job seems to sense that for her husband to “persist in his integrity” in this situation, he cannot do both. She seems to be arguing that “if Job holds on to integrity in the sense of conformity to religious norm and blesses God as he did before, . . . he will be committing an act of deceit. If he holds on to integrity in the sense of honesty, then he must curse God and violate social integrity, which forbids such cursing.” (Ibid.)

Job, however, tells her she is being foolish. In fact, the Hebrew here is rather stronger – the commentary notes that a more accurate contemporary translation would be that he tells her she is “talking trash”! Job insists that there is no conflict between religious integrity and personal honesty. We are again assured by the narrator that “in all this Job did not sin with his lips.” (2:10)

This is where our reading this morning ends, but it is not the end of Chapter 2. As the chapter ends, Job’s three friends – Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite – hearing of all of his troubles meet together to come to console and comfort him. On seeing his state, they tear their own clothes, weep loudly, throw dust upon their own heads, then sit down in the dirt with him. For a week they sit there with him in silence.

So what are we to make of these initial scenes from the story of Job. If St. John Chrysostom is right and there are “medicines for the soul” to be found here, what are they? I suggest there are a couple of things to be learned here which may be of some comfort in our modern age. The first is found in this book’s rejection of the facile answers of an older “wisdom religion” tradition.

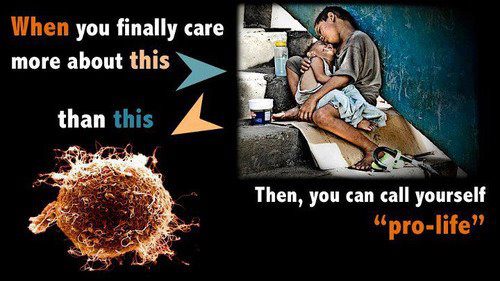

I am sure that we have all, at one time or another, faced the death of a loved one, the loss of something or someone precious to us, or some other personal tragedy or difficult situation; or that if we have not, we surely will. And I’m equally sure that in such a situation we are all prone to ask an interior question along the lines of “Why me?” or “What have I done to deserve this?”

That older “wisdom religion” which runs through our faith tradition encourages that sort of thinking. Elsewhere in Holy Scripture, in the Book of Proverbs, for example, we are told:

Walk in the way of the good, and keep to the paths of the just. For the upright will abide in the land, and the innocent will remain in it; but the wicked will be cut off from the land, and the treacherous will be rooted out of it. (2:20-22)

And again:

The Lord’s curse is on the house of the wicked, but he blesses the abode of the righteous. Toward the scorners he is scornful, but to the humble he shows favor. The wise will inherit honor, but stubborn fools, disgrace. (3:33-35)

The message seems clear: “Do good, you’ll be rewarded with good. Do bad, you’ll be punished with bad.” It suggests a sort of post hoc ergo propter hoc (Latin for “after this, therefore because of this”) assumption that if something bad has happened to me, I must have done something bad to deserve it. And it’s not too far to the next thought, “I’ve not only done something bad, I am bad.” But post hoc ergo proper hoc is a logical fallacy and that line of reasoning is just plain wrong, as the story of Job clearly demonstrates.

Although this Book of Job is part of the “wisdom literature” and firmly grounded in the wisdom tradition, it offers a sound critique of that tradition. The character Job, an upright and righteous man, a man of integrity, is visited by loss and calamity through no fault of his own. He does not deserve what happens to him. His story avoids the clicheic simplicity of the older wisdom tradition and rejects that “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” thinking to which we are all prone. His story “is, in fact, an impassioned assertion of the awareness that the simple moralism of most wise men is hardly enough.” (Jay G. Williams, Understanding the Old Testament, Barrons Educational Series: 1972, page 267)

Stuff sometimes happens in a person’s life, as it does in the story of Job, that he or she does not deserve and for which he or she is not to blame! Stuff sometimes happens in your life that you do not deserve, and you are not to blame for it! That is the first bit of medicine we find in these introductory scenes in the Book of Job. Give up the “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” thinking, and stop beating yourself up over things you can’t control!

The second bit of “medicine” is the book’s apparent rejection of religious ritual as a touchstone of goodness and integrity. It is important that Job is afflicted with “loathsome sores” because, according to Jewish law in the Book of Leviticus, a person inflicted with a skin disease is ritually impure and an outcast from society. Such an individual is referred to in Hebrew as a metzorah. Jewish law as set forth in the Book of Leviticus requires the metzorah to be shunned; the person must live alone outside the confines of the community. In chapter 13 of Leviticus we read that he or she must show their sores to the local priest, and then

. . . shall wear torn clothes and let the hair of his head be disheveled; and he shall cover his upper lip and cry out, “Unclean, unclean.” He shall remain unclean as long as he has the disease; he is unclean. He shall live alone; his dwelling shall be outside the camp. (Lev. 13:45-46)

Job, however, does none of this; he does not follow any of the Levitical requirements, nor do his friends. Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar do not shun him, nor leave him alone outside the community. Integrity, this story assures us, does not rest in conformity to religious norms.

This should come as good news, as balm for our modern and postmodern souls, because, as Emerging Church blogger Drew Tatsuko has pointed out, “religions that make these exclusive claims to Truth demand conformity; religions that demand conformity tend to abuse non-conformists . . . ; and, in history God is [most frequently] revealed among the non-conformists.”

Now this does not mean that, in its rejection of the wisdom tradition, the Book of Job is telling to not live a good and honorable life, or that in its rejection of religious ritual as definitive of personal integrity the book is telling us to abandon our norms of worship and behavior. Rather, what we should take from the story of Job is that life is a set of questions. If there is truth to be found in this book, or in any of the books of the Bible, it is to be found in the process of struggling with those questions. We will wrestle with the questions of Job throughout this month during which our Old Testament readings will be drawn from it. The book has 42 chapters so, clearly, in four weeks of readings we are not going to cover it in depth. But I hope to demonstrate over the course of these sermons that, as my friend Greg Jenks who is Academic Dean at St Francis Theological College, Brisbane, Australia, says, Job “is a biblical text that celebrates the lack of a compelling answer, and instead calls us to faithfulness that sees beyond suffering to a meaning beyond human comprehension.”

I hope you will find, as I said at the beginning of this introductory sermon, that Job is a book which offers us a variety of remedies, a selection of alternative truths for whatever besets our spirits; it also provides a glimpse at the over-arching meta-truth that sustains our lives, namely the awesome power of God.

Jonah’s a fool! Trying to flee “from the presence of the Lord.” As if! This lesson today is an interesting contrast to Sunday’s Eucharistic Lectionary reading from Book of Job (Job 23:1-9,16-17) in which Job was bewildered and confused because he felt unable to find God: “Oh, that I knew where I might find him, that I might come even to his dwelling!” (Job 23:2) Jonah, on the other hand, would be perfectly happy never to find, or be found by, God.

Jonah’s a fool! Trying to flee “from the presence of the Lord.” As if! This lesson today is an interesting contrast to Sunday’s Eucharistic Lectionary reading from Book of Job (Job 23:1-9,16-17) in which Job was bewildered and confused because he felt unable to find God: “Oh, that I knew where I might find him, that I might come even to his dwelling!” (Job 23:2) Jonah, on the other hand, would be perfectly happy never to find, or be found by, God. In last week’s reading from the Old Testament, you will remember, God gave Satan permission to test the righteousness of a man of integrity named Job. First all of Job’s possessions and his family are taken from him: his oxen and donkeys are carried off by Sabeans; his sheep are burned up in a fire; his camels are stolen by the invading Chaldeans; and the collapse of a house kills all of Job’s ten children. But Job, being a righteous man, does not curse God; instead, he shaves his head, tears his clothes, and says, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return there; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” Job does not sin or curse God. (1:21-22)

In last week’s reading from the Old Testament, you will remember, God gave Satan permission to test the righteousness of a man of integrity named Job. First all of Job’s possessions and his family are taken from him: his oxen and donkeys are carried off by Sabeans; his sheep are burned up in a fire; his camels are stolen by the invading Chaldeans; and the collapse of a house kills all of Job’s ten children. But Job, being a righteous man, does not curse God; instead, he shaves his head, tears his clothes, and says, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return there; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” Job does not sin or curse God. (1:21-22) I know two things today that I didn’t know earlier in the week. First, I know that people read our sign. I got two telephone calls and one email telling me that we had misspelled “patience” on the sign. Second, I know that people won’t believe you when you tell them you did it on purpose. But I really did name this sermon series “The Patients (P-A-T-I-E-N-T-S) of Job” for reasons that I hope will become clear very shortly.

I know two things today that I didn’t know earlier in the week. First, I know that people read our sign. I got two telephone calls and one email telling me that we had misspelled “patience” on the sign. Second, I know that people won’t believe you when you tell them you did it on purpose. But I really did name this sermon series “The Patients (P-A-T-I-E-N-T-S) of Job” for reasons that I hope will become clear very shortly.

From time to time, people tell me that they have appreciated something I’ve said or done and I try to remember to say, “Thank you.” But inside, I really don’t think about compliments very much. It’s not that I don’t appreciated them, but I don’t do what I do to be complimented, and I really don’t think that I have much to do with it when whatever I do has gone well or had a positive impact on someone. I sort of take Paul’s attitude from the Letters to the Romans and the Galatians: “It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 20:2) and “I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me” (Rom. 15:18). So I do think, generally, that the answer to Eliphaz’s question is, “Yes.” Mortals can be of use to God. But there are times I would answer otherwise.

From time to time, people tell me that they have appreciated something I’ve said or done and I try to remember to say, “Thank you.” But inside, I really don’t think about compliments very much. It’s not that I don’t appreciated them, but I don’t do what I do to be complimented, and I really don’t think that I have much to do with it when whatever I do has gone well or had a positive impact on someone. I sort of take Paul’s attitude from the Letters to the Romans and the Galatians: “It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 20:2) and “I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me” (Rom. 15:18). So I do think, generally, that the answer to Eliphaz’s question is, “Yes.” Mortals can be of use to God. But there are times I would answer otherwise.  This morning I was struck by the absolutely opposite attitudes displayed in these two readings. The morning psalm invites God to try the worshipper; the first reading of the day demands the right to try God. I think these poles really do represent the spiritual pendulum on which most humans swing; they circumscribe our ambivalent and ambiguous relationship with the Almighty.

This morning I was struck by the absolutely opposite attitudes displayed in these two readings. The morning psalm invites God to try the worshipper; the first reading of the day demands the right to try God. I think these poles really do represent the spiritual pendulum on which most humans swing; they circumscribe our ambivalent and ambiguous relationship with the Almighty.  Wow! Does this look familiar? The second chapter of Job begins with a scene nearly identical to that which we considered yesterday. Satan (with other heavenly beings) presents himself in the heavenly throne room and, once again, God and Satan have a conversation about Job and, once again, the bet is made. In fact, it’s sort of “double down” time! Yesterday, I argued that although the Book of Job is fiction it (like the other forms of literature found in Holy Scripture) embodies truth.

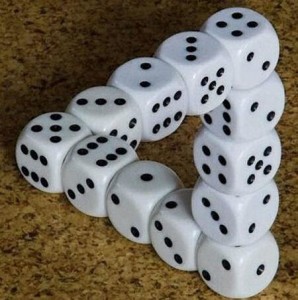

Wow! Does this look familiar? The second chapter of Job begins with a scene nearly identical to that which we considered yesterday. Satan (with other heavenly beings) presents himself in the heavenly throne room and, once again, God and Satan have a conversation about Job and, once again, the bet is made. In fact, it’s sort of “double down” time! Yesterday, I argued that although the Book of Job is fiction it (like the other forms of literature found in Holy Scripture) embodies truth. A later selection from the Book of Job was called up by the Sunday Eucharistic Lectionary several weeks ago. In my sermon I said to the congregation that the Book of Job is fiction (which it is). You should have seen the look on one of my parishioners’ face! There’s a fellow in the congregation who is, shall we say, conservative with regard to the Bible. While I don’t believe he actually considers the Bible to be the inerrant word of God per se, he’s pretty sure that it is to be taken with the highest degree of certainty and words like “myth” or “fiction” applied to Scripture are not to his liking. I swear I thought he might have an apoplectic fit right there in his pew! But let’s be honest: do we really think that God and Satan are engaged (or have ever been engaged) in a game of chance involving the lives of human beings?

A later selection from the Book of Job was called up by the Sunday Eucharistic Lectionary several weeks ago. In my sermon I said to the congregation that the Book of Job is fiction (which it is). You should have seen the look on one of my parishioners’ face! There’s a fellow in the congregation who is, shall we say, conservative with regard to the Bible. While I don’t believe he actually considers the Bible to be the inerrant word of God per se, he’s pretty sure that it is to be taken with the highest degree of certainty and words like “myth” or “fiction” applied to Scripture are not to his liking. I swear I thought he might have an apoplectic fit right there in his pew! But let’s be honest: do we really think that God and Satan are engaged (or have ever been engaged) in a game of chance involving the lives of human beings? Our first reading this morning is from the Book of Job, which in the Jewish organization of Scripture is part of the Ketuvim or “Writings” and is considered one of the Sifrei Emet or “Books of Truth”, which is really quite interesting since it is generally acknowledged to be a work of fiction. It tells the story of Iyyobh (“Job”), who is described as a righteous man and who becomes the subject of a wager between a character called “Satan” and another character called “God”. I put it that way to underscore that this text is not relating to us any historical facts about God, or Satan, or a man named Job; it is, rather, telling a story in which characters representing God, Satan, and human beings in general help us to understand something about reality.

Our first reading this morning is from the Book of Job, which in the Jewish organization of Scripture is part of the Ketuvim or “Writings” and is considered one of the Sifrei Emet or “Books of Truth”, which is really quite interesting since it is generally acknowledged to be a work of fiction. It tells the story of Iyyobh (“Job”), who is described as a righteous man and who becomes the subject of a wager between a character called “Satan” and another character called “God”. I put it that way to underscore that this text is not relating to us any historical facts about God, or Satan, or a man named Job; it is, rather, telling a story in which characters representing God, Satan, and human beings in general help us to understand something about reality. Job wants answers about justice but God goes into a rant about the creation: the sea, the stars, the sky, the earth, the whole shebang! As the speech goes on for several chapters, God will talk about all the wild animals, even the ostrich, who is incredibly foolishness but very very speedy. What are we to make of this? Job wants fairness; he wants what’s right! And God’s answer is, “Hey! Look at that ostrich I made! It’s stupid but, wow, is it fast!” What’s the point?

Job wants answers about justice but God goes into a rant about the creation: the sea, the stars, the sky, the earth, the whole shebang! As the speech goes on for several chapters, God will talk about all the wild animals, even the ostrich, who is incredibly foolishness but very very speedy. What are we to make of this? Job wants fairness; he wants what’s right! And God’s answer is, “Hey! Look at that ostrich I made! It’s stupid but, wow, is it fast!” What’s the point?