====================

A sermon offered on Palm Sunday, March 29, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(At the blessing of the Palms, Zechariah 9:9-12 was read. The lessons at the Mass were Isaiah 50:4-9a; Psalm 31:9-16; Philippians 2:5-11; and Mark 11:1-11. The Passion according to Mark, Mk 14:1-15:47 was read at the conclusion of the service. Other than Zechariah, these lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

The four evangelists are traditionally represented by iconic depictions of the emphasis of their gospels. John, whose gospel is the longest and most different of the four tellings of Jesus’ story, is represented by an eagle because he emphasizes the divinity of Christ. Matthew, on the other hand, begins his gospel with Jesus’ genealogy and emphasizes the humanity of the Savior, so he is represented by a man. Luke emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ ministry and mission; thus, he is represented by an ox or bull (often winged), the sort of animal offered in the Temple.

The four evangelists are traditionally represented by iconic depictions of the emphasis of their gospels. John, whose gospel is the longest and most different of the four tellings of Jesus’ story, is represented by an eagle because he emphasizes the divinity of Christ. Matthew, on the other hand, begins his gospel with Jesus’ genealogy and emphasizes the humanity of the Savior, so he is represented by a man. Luke emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ ministry and mission; thus, he is represented by an ox or bull (often winged), the sort of animal offered in the Temple.

Mark, from whose gospel we read today, both the story of Jesus’ “triumphal entry” into Jerusalem and the story of his Passion, is represented by a winged lion, an emblem of kingship, because his emphasis is both the Jewish expectation that the Messiah would be of lineage of King David and that Jesus’ mission was rather different, the ushering in of the kingdom of God.

Which, I think, gives us an interpretive tool for understanding why Mark tells the story of the “triumphal entry” as he does. John, who (as I said) is most interested in portraying Jesus as divine, blows by this episode in two sentences: basically he says, “There was a crowd; they cheered; Jesus rode a donkey. Now back to the important stuff.” Matthew, who (remember) emphasizes Jesus’ humanity, adds the story of Jesus losing his temper with the money changers and animal merchants in the Temple courtyard. Luke, who is intent on portraying Jesus as the sacrificial Messiah predicted by prophecy, adds a second donkey to the parade (because he apparently misunderstands Zechariah, tells us that Jesus wept over Jerusalem on the way in to town, includes a conversation between Jesus and some Pharisees about the stones singing “Hosanna,” follows Matthew in adding the cleansing of the Temple, and concludes the story with Jesus staying in the Temple and teaching while the chief priests figure out how to kill him.

Mark, however…. Mark keeps it simple – not as simple as John, but direct and to the point. But what is his point? In the NRSV translation of Mark 11:1-11 which we read at the blessing of the palms there are 232 words. 144 of them are spent describing the process of locating, procuring, saddling (so to speak), and sitting astride the donkey. Only 67 words actually describe Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. And 21 words finish the pericope with its anti-climactic ending, “…and when he had looked around at everything, as it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the twelve.” I find that intriguing.

Now it may seem silly to count words, but this is one of the things bible scholars do. Sometimes, when studying a book or section of the Bible, we can better understand an author’s theme by examining the frequency of word usage. For example, the use of love in the First Letter of John and the repeated use of immediately in Mark’s gospel are enlightening. So noting the number of words invested in telling the different parts of a story can, perhaps, tell us what the author felt important, and Mark seems to think the getting the donkey is roughly twice as important as Jesus actually riding it into the city!

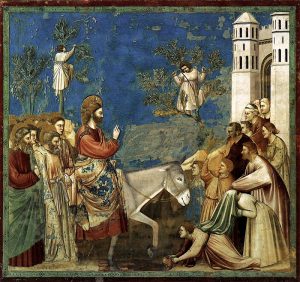

So let’s first look at the lesser important part of the story, Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. What’s going on here? In a word, what’s going on here is politics! Jesus is making a huge political statement; first, he is very clearly acting out the prophecy of Zechariah: “Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” (Zec 9:9) He is making an acted-out, very visual claim to be the king!

Furthermore, he is doing it in a way that mocks the Roman governor. It was the practice of the governor, at this time Pontius Pilate, to make a show of force at the time of the Passover. Because so many potentially rebellious Jews were gathered in Jerusalem to celebrate the feast of an historic liberation, the Exodus from Egypt, the Romans feared the possibility of open revolt. So at the beginning of the festival, the governor would come to Jerusalem from his usual residence at the imperial seaport of Caesarea Maritima, entering the city from the west, riding his war stallion or perhaps in a chariot of state, at the head of long column of armed soldiers. Jesus, on the other hand, is approaching from the east, coming up from Jericho and the Jordan valley, over the Mount of Olives through the peasant villages of Bethphage and Bethany. Riding the lowliest of beasts of burden, the least military of animals, Jesus is making the point that the kingdom of Heaven is about something other than regal authority and military might, something other than power elites and superiority over others.

And, I suggest, that’s why Mark spends so many words telling us about the locating, procuring, preparing, and mounting of the donkey.

There is a legendary suggestion that the two unnamed disciples whom Jesus’ sent to get the colt were none other than James and John, the sons of Zebedee, who just before this (at the end of Mark’s Chapter 10, in fact) had come to Jesus and said to him, “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.” (10:37) None of the evangelist tell us the names of the two disciples sent to get the donkey, but wouldn’t that have been a graphic way for Jesus to demonstrate to them that “whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all?” (10:43-44) It is certainly a clear sign that life in the kingdom is not a glamorous thing; it’s not a life of war stallions and chariots, palaces and fine meals, or relaxing at your ease while others bear the burdens. It is not that sort of life for the king, and it is not that sort of life for his followers.

As Tom Long, who teaches preaching at Candler School of Theology, has noted,

The disciples in Mark get a boat ready for Jesus, find out how much food is on hand for the multitude, secure the room and prepare the table for the Last Supper and, of course, chase down a donkey that the Lord needs to enter Jerusalem. Whatever they may have heard when Jesus beckoned, “Follow me,” it has led them into a ministry of handling the gritty details of everyday life. (Donkey Fetchers, in The Christian Century, April 4, 2006, page 18)

Life in the kingdom, where all are servants, is common, routine, mundane, and often exhausting. This, I think, is why Mark makes more of getting the donkey than he does of Jesus’ riding it into Jerusalem. He wants us to understand that life in the kingdom is the life of the king whose faithfulness to his God and to his understanding of his mission required him to take up the cross, the king who said, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” (Mk 8:34-35)

Poet Mary Oliver imagined this story from the point of view of the donkey when she wrote:

On the outskirts of Jerusalem

the donkey waited.

Not especially brave, or filled with understanding,

he stood and waited.

How horses, turned out into the meadow,

leap with delight!

How doves, released from their cages,

clatter away, splashed with sunlight!

But the donkey, tied to a tree as usual, waited.

Then he let himself be led away.

Then he let the stranger mount.

Never had he seen such crowds!

And I wonder if he at all imagined what was to happen.

Still, he was what he had always been: small, dark, obedient.

I hope, finally, he felt brave.

I hope, finally, he loved the man who rode so lightly upon him,

as he lifted one dusty hoof, and stepped, as he had to, forward.

(The Poet Thinks about the Donkey, Thirst, Beacon Press, 2007)

The One who rode the donkey also “stepped, as he had to, forward,” into that most common, most routine, most mundane, and most exhausting fact of life. He stepped willingly into death. Therefore,

“Death has been swallowed up in victory.”

“Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?”

***

Thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore . . . be steadfast, immovable, always excelling in the work of the Lord, [however common or routine or mundane or exhausting] because you know that in the Lord your labor is not in vain.” (1 Cor 15:54-55,57-58)

Let us pray:

Almighty God, whose dear Son went not up to joy but first he suffered pain, and entered not into glory before he was crucified: Mercifully grant that we, walking in the way of the cross, may find it none other that the way of life and peace; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. (Collect for Monday in Holy Week, BCP 1979, page 220)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Christology is one of those odd words of the Christian tradition that one doesn’t hear much in church but which one hears a lot in academic circles. Christology is defined as “the field of study within Christian theology which is primarily concerned with the ontology and person of Jesus as recorded in the canonical Gospels and the epistles of the New Testament.”[1] That’s really helpful, isn’t it? Begs the questions, “What is theology? What is ontology? What is a ‘canonical Gospel’?”

Christology is one of those odd words of the Christian tradition that one doesn’t hear much in church but which one hears a lot in academic circles. Christology is defined as “the field of study within Christian theology which is primarily concerned with the ontology and person of Jesus as recorded in the canonical Gospels and the epistles of the New Testament.”[1] That’s really helpful, isn’t it? Begs the questions, “What is theology? What is ontology? What is a ‘canonical Gospel’?” Today we are commemorating Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem at the beginning of the week that would culminate in his death on the cross of Calvary. Somewhat contrary to common sense, this has come to be called the “triumphal entry.” I don’t know who first applied this term to Jesus making his way from Bethany and Bethphage, through the Kidron Valley, also known as the valley of Jehosophat or the valley of decision, into the holy city. I’ve often thought that whoever it was must surely have been a master of irony, or perhaps of sarcasm, for the procession was anything but a triumph!

Today we are commemorating Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem at the beginning of the week that would culminate in his death on the cross of Calvary. Somewhat contrary to common sense, this has come to be called the “triumphal entry.” I don’t know who first applied this term to Jesus making his way from Bethany and Bethphage, through the Kidron Valley, also known as the valley of Jehosophat or the valley of decision, into the holy city. I’ve often thought that whoever it was must surely have been a master of irony, or perhaps of sarcasm, for the procession was anything but a triumph! Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.

Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.  The four evangelists are traditionally represented by iconic depictions of the emphasis of their gospels. John, whose gospel is the longest and most different of the four tellings of Jesus’ story, is represented by an eagle because he emphasizes the divinity of Christ. Matthew, on the other hand, begins his gospel with Jesus’ genealogy and emphasizes the humanity of the Savior, so he is represented by a man. Luke emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ ministry and mission; thus, he is represented by an ox or bull (often winged), the sort of animal offered in the Temple.

The four evangelists are traditionally represented by iconic depictions of the emphasis of their gospels. John, whose gospel is the longest and most different of the four tellings of Jesus’ story, is represented by an eagle because he emphasizes the divinity of Christ. Matthew, on the other hand, begins his gospel with Jesus’ genealogy and emphasizes the humanity of the Savior, so he is represented by a man. Luke emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ ministry and mission; thus, he is represented by an ox or bull (often winged), the sort of animal offered in the Temple.

As Mark constructs his version of the story of Jesus, the Lord has just advised his followers to cut off body parts that might cause them to sin saying it is better to enter Heaven maimed than to be thrown into Hell where “the fire is never quenched.” To this admonition, then, Mark adds this statement about salt.

As Mark constructs his version of the story of Jesus, the Lord has just advised his followers to cut off body parts that might cause them to sin saying it is better to enter Heaven maimed than to be thrown into Hell where “the fire is never quenched.” To this admonition, then, Mark adds this statement about salt. Clothing is a common metaphor in Holy Scripture. Clean clothing is often a portrayal of righteousness or forgiveness. Everyone is familiar with the vision of John of Patmos recorded in the Book of Revelation:

Clothing is a common metaphor in Holy Scripture. Clean clothing is often a portrayal of righteousness or forgiveness. Everyone is familiar with the vision of John of Patmos recorded in the Book of Revelation:

I know I’ve read this bit of Zechariah before, but I don’t think I’ve ever paid any attention to it. This morning, the image of parents “piercing” their own children who happen to be prophets and that of “the wounds I received in the house of my friends” really hit home! Strife within families and between friends is here the recompense paid by God to false prophets, but it seems to be the lot of the prophet, the priest, or the ardent advocate in any age. I am reminded of Jesus’ quoting Micah to the effect that “your enemies are members of your own household.” (Micah 7:6; cf Matt. 10:35-36 and Luke 12:52-53) Speaking on behalf of God or any god or any cause is never easy; it leads to misunderstanding and conflict – just look at what happened in many families during the recently passed political campaigns.

I know I’ve read this bit of Zechariah before, but I don’t think I’ve ever paid any attention to it. This morning, the image of parents “piercing” their own children who happen to be prophets and that of “the wounds I received in the house of my friends” really hit home! Strife within families and between friends is here the recompense paid by God to false prophets, but it seems to be the lot of the prophet, the priest, or the ardent advocate in any age. I am reminded of Jesus’ quoting Micah to the effect that “your enemies are members of your own household.” (Micah 7:6; cf Matt. 10:35-36 and Luke 12:52-53) Speaking on behalf of God or any god or any cause is never easy; it leads to misunderstanding and conflict – just look at what happened in many families during the recently passed political campaigns.