====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Seventh Sunday after Pentecost, July 3, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 9C of the Revised Common Lectionary: Isaiah 66:10-14; Psalm 66:1-8; Galatians 6:1-16; and St. Luke 10:1-11,16-20. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Take just a quick look at me and you will know that I like to eat, probably too much. I like to cook; I like to entertain and have dinner parties; I like to go to dinner parties; I like to enjoy good restaurants; I like to go to not very good restaurants, too. I like to eat. So when I read a story in which Jesus tells his followers, not once but twice, to eat, it makes me happy. Except for the part where he tells us to not be picky. “Eat and drink whatever they provide . . . eat what is set before you.” (Lk 10:7,8) Yeah . . . but, Jesus, what if it’s, like, okra or liver or raw oysters?

Take just a quick look at me and you will know that I like to eat, probably too much. I like to cook; I like to entertain and have dinner parties; I like to go to dinner parties; I like to enjoy good restaurants; I like to go to not very good restaurants, too. I like to eat. So when I read a story in which Jesus tells his followers, not once but twice, to eat, it makes me happy. Except for the part where he tells us to not be picky. “Eat and drink whatever they provide . . . eat what is set before you.” (Lk 10:7,8) Yeah . . . but, Jesus, what if it’s, like, okra or liver or raw oysters?

I have a friend who is a priest in the Anglican Church of Canada. He grew up in the cattle country of Alberta, studied and was ordained in Ontario, and took his first solo assignment on the coast of Labrador, where he served three small seaside parishes. On his arrival, he was quickly invited to dinner by nearly every family in the three congregations and scheduled several of these in rapid succession. Unlike me, my friend loves seafood and was looking forward to feasting on the fresh catch from off the maritime coast. But instead of fresh seafood, his first hosts fed him canned beef. So did the next . . . and the next . . . and at the end of his first week in Labrador, a place known for its fishing industry, he’d had four canned beef dinners.

He also got a call from the bishop at the end of that first week and, when asked how things were going, expressed his disappointment in these dinner offerings. The bishop laughed out loud and then explained to my friend that his parishioners were fisher folk. Seafood was cheap and abundant for them, so that’s what they had every day at nearly every meal. For them, a special occasion, like dinner with the vicar, required a special meal and “special” to them meant beef; most of them couldn’t afford fresh meat from the butcher, so next best was a canned beef roast. The priest might be disappointed, but his parishioners were paying him the highest compliment of hospitality, serving what for them was the most festive of meals. “Eat whatever they provide; eat what is set before you.” Receive hospitality graciously for you do not know the circumstances from whence it is extended.

Paul K. Palumbo, a Lutheran missionary, has written of his similar experience among the poorest of the poor in Latin America:

[E]very time we sat to eat rice and beans, we received . . . a steady diet of honor and humility. To be served rice and beans prepared over a stone oven fueled by wood in dirt-floor houses on the only little table in the house was an honor. To be told the stories of our host families’ lives over the meal was an honor. To have the tiny house in which we were guests rearranged so that we might have a bedroom to ourselves was an honor. The tendency, of course, was to raise one objection or another, that what was set before us was not to our taste or, more typically among our group, that it was too much for a poor family to spend on rich North Americans. These objections were both true, perhaps, but for the sake of the gift and for the sake of learning to receive, it was important to eat what was set before us. (Texts in Context: Eating What Is Set before You)

And that, I think, is the point of this admonition that Jesus gives the 70 (or the 72) not once but twice, to eat what they are provided; they are to learn to receive. They had a lot to give, teaching and admonition, the good news of the nearness of the kingdom of heaven, healing of infirmities both physical and spiritual, but they also had to learn, learn to receive.

That’s a very hard lesson to learn. As some of you know, my wife was hospitalized for several days week before last and being with her in the hospital reminded me of my own experiences being a patient, and how difficult that is! You’re lying in bed (a strange electrical bed all sorts of controls that, even if you can reach them, you can’t figure out). Usually you’re tethered by a needle in your arm to a bag of something hanging out of reach behind your head; you may be wired up to some sort of monitor or connected by a plastic tube to an oxygen valve in the wall. You can’t even get out of bed without assistance, let alone do anything else. You can’t just go to the kitchen and make yourself a meal or a late-night TV snack. You can’t wander down the hall to find something to read in the next room. You can’t do anything for yourself. You must receive the ministrations, the ministry of others. And some of us are just not very good at that because we’ve never learned how to do it. We hear Paul tell the Galatians, “Bear one another’s burdens,” and what we understand is that we must be the burden-bearers; we seldom, if ever, understand that sometimes we must receive the gift of others bearing our burdens.

This is why, instead of sending his messengers out fully equipped and prepared, Jesus sends them with “no purse, no bag, [not even] sandals,” (Lk 10:4) and instructs them to “eat whatever is put before you.” In order to learn to receive, we have to eat whatever we are served, even if it is our own sense of self-sufficiency; we have to swallow our pride and in doing so we receive a precious gift.

Melissa Bane Sevier is a Presbyterian pastor who writes of her experience traveling abroad as an illustration of this gospel passage:

Jesus tells the seventy to receive whatever hospitality is offered. That’s odd. We expect to be told to share hospitality, not to receive it. How happy we are when someone thanks us for a nice meal or is grateful to have a place to stay. When the worshiping community extends hospitality to the stranger, the person on the margins, the immigrant, that community finds itself warmed and renewed by the act of giving.

And yet, receiving is also a gift to oneself and to the giver. Some of the most memorable travel moments I’ve ever experienced happened in some of the poorest places, when my friends and I were offered a simple meal of homemade tortillas, bananas and papayas picked from village trees, and ice cold Coke bought from the local tienda.

Thousands of miles from home, we were served a meal that transcended language and culture with its hospitality and welcome. It was more than we could have asked or expected, and it made us feel at home.

Jesus knew what he was doing when he sent out the seventy in twos. We don’t have to go to a foreign country to be on the journey together. We share memories and adventures. Sometimes we remember the wolves, and can laugh together at the ones who were mean but not really dangerous. We encourage each other to watch out for the truly alarming. But mostly, we talk about those lovely situations where we were given incredible hospitality, where we were welcomed. Sometimes it is hard for us to accept those gifts of hospitality, for we have been trained to give rather than to receive. But Jesus wanted the seventy to know the joy of receiving. (Melissa Bane Sevier, Two-Way Blessing)

And why do we have to learn this joy, this lesson of receiving from others?

Do you remember the old television show All In The Family. The main character, Archie Bunker, was fond of saying, “As the Good Book says . . . .” and then he would quote Poor Richard’s Almanac, or an Aesop’s Fable, or Ann Landers, or any number of other sources, but never anything that actually came out of Scripture. How many of us grew up believing that “God helps those who help themselves” was straight out of the Bible? Well . . . it isn’t! And, in fact, it’s diametrically opposed to the lessons of Scripture! “There is no king that can be saved by a mighty army; a strong man is not delivered by his great strength,” says the Psalmist (33:16; BCP version). In Proverbs we read, “Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not rely on your own insight.” (3:5, NRS) And again the Psalmist says, “It is better to rely on the Lord than to put any trust in flesh,” (118:8, BCP version) even – or perhaps especially – our own!

We have to give up our sense of self-sufficiency; we have to learn to receive the ministry of others so that we can receive the ministry of God, so that we can trust in the Lord with all our heart. “For thus says the Lord:

I will extend prosperity to [Jerusalem] like a river,

and the wealth of the nations like an overflowing stream;

and you shall nurse and be carried on her arm,

and dandled on her knees.

As a mother comforts her child,

so I will comfort you;

you shall be comforted in Jerusalem.

You shall see, and your heart shall rejoice;

your bodies shall flourish like the grass . . . .

(Is 66:12-13)

Theologian Elizabeth Webb (an Episcopalian, by the way) writes about this passage from the Book of Isaiah, echoing Pastor Sevier’s observation that the joy of receiving hospitality “makes us feel at home:”

The comfort that Mother God provides for her people is the comfort of home; restoring the people to the place they belong, rebuilding their ruins, and washing them in riches and security (see also 49:13, 51:13, 52:9, and 54:11). Under God’s nurturing care, the very bodies and spirits of God’s people receive restoration (verse 14).

The word translated “bodies” in the NRSV should more properly be translated “bones,” which speaks to the sense that despair can settle in and take over our very essence, and which emphasizes that God can reach in and restore that essence to joy. The home in this world that God provides for us is within the circle of God’s own arms, and in that place the tired old bones of humanity flourish again. Deep within our bones we are weary and broken, and deep within our bones God’s nurturing love reaches in and restores.

Joy and comfort. Milk and water. Weary bones refreshed and restored. In the midst of the thundering of condemnation and retribution, it is this quiet passage of maternal care and human delight that gestures more particularly to the presence of God with God’s people that their bone-tired bodies and spirits might flourish again, like the grass. (Elizabeth Webb, Commentary on Isaiah 66:10-14)

It is precisely that sort of internal transformation that Paul writes about in today’s passage from the Letter to the Galatians when he says that, by “the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, . . . the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world.” In their book The First Paul: Reclaiming the Radical Visionary (HarperCollins:New York, 2010), Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan, argue that what Paul means is that he has left behind “the world of imperial normalcy,” the world characterized by “‘domination systems,’ societies ruled by a few who used their power, wealth, and ‘wisdom’ to shape the social system in their own self-interest.” (Pg 136)

In its place, transformed by God’s maternal hospitality in Jesus, Paul embarks on what Prof. Sarah Henrich calls the “crazy project” of imagining a world where human beings “eschew the measurements of value used in the everyday world,” where people “devote themselves to one another’s well being, confident that there would be others who would care for them.” In other words, Paul urges the Galatians and us to imagine (and create!) a world where we have learned the lesson of receiving hospitality, where we know how to accept the ministration and the ministry of others, and thus can receive the maternal hospitality of God.

Henrich writes:

Perhaps the best way to fire our imaginations and live in accord with [Paul’s vision] requires us to do the burden bearing more graciously. That is, we are privileged to hear one another’s dreams and desires, to continuously extend the tables at which we sit, the suppers we call Holy, to make room for folk who will see gifts and challenges that surprise us. In listening, in surprise, in hospitality for a moment we catch a richer glimpse of God’s reality and find the energy of the Spirit, lest we grow weary. (Sarah Henrich, Commentary on Galatians 6:[1-6]7-16)

“Carry no purse, no bag, no sandals.” When you enter a house, say first “Peace to this house!” “Eat and drink what is provided; eat what is set before you.” It may be okra or oysters or canned beef, but whatever it is it will be more than you could have asked or expected, and it will make you feel at home. Receive from others the gift of their bearing your burdens, and you will know the comfort that Mother God provides for her people. “As a mother comforts her child, so [God] will comfort you;” your bone-tired body and spirit will flourish again; and your name will be written in heaven. Amen.

(Note: The accompanying illustration is a plate of Cajun “Dirty, Dirty Rice” which includes sautéed pork liver and okra. This is definitely not something I would ever want to eat, but my readers may be interested. The recipe can be found here.)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

As many of you know, this past week was a harrowing one for my wife and for me; specifically, Wednesday was one of those days you would rather not have to live through. In the afternoon, I was told by a urologist that I probably have prostate cancer, and later that night Evelyn nearly died from pulmonary embolism. She is OK now – I will be leaving right after this service to bring her home from the hospital – and my diagnosis will be either confirmed or proven wrong by a biopsy in about a month.

As many of you know, this past week was a harrowing one for my wife and for me; specifically, Wednesday was one of those days you would rather not have to live through. In the afternoon, I was told by a urologist that I probably have prostate cancer, and later that night Evelyn nearly died from pulmonary embolism. She is OK now – I will be leaving right after this service to bring her home from the hospital – and my diagnosis will be either confirmed or proven wrong by a biopsy in about a month.  The week of the summer solstice was an interesting one in the Funston household.

The week of the summer solstice was an interesting one in the Funston household.  Twenty-four years and 363 days ago I was made a priest; some what more than a year more than that, I have been a deacon. I have been in parish ministry for more than 26 years and on Tuesday I will celebrate the 25th anniversary of my ordination to the Sacred Prebyterate.

Twenty-four years and 363 days ago I was made a priest; some what more than a year more than that, I have been a deacon. I have been in parish ministry for more than 26 years and on Tuesday I will celebrate the 25th anniversary of my ordination to the Sacred Prebyterate. I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience.

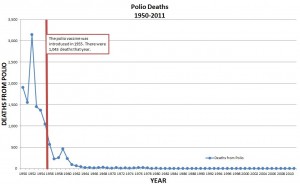

I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience. The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from

The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from  On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.

On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.  Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.

Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.

Dr. Robert Waldinger is the current director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development which is something called “a longitudinal cohort study” in which the same individuals are observed over a long study period. It is the longest running study of this kind in history. For 75 years researchers have tracked the lives of 724 men from all walks of life.

Dr. Robert Waldinger is the current director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development which is something called “a longitudinal cohort study” in which the same individuals are observed over a long study period. It is the longest running study of this kind in history. For 75 years researchers have tracked the lives of 724 men from all walks of life.

There’s a lady who’s sure

There’s a lady who’s sure In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.

In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.