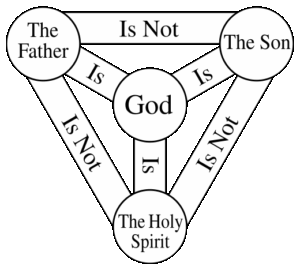

A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

Then the Immigration and Customs Enforcement doubled down on Mr. Trump’s promises of “mass deportations” across the country, but especially in Southern California and particularly in Los Angeles (where I grew up, by the way). People took to the streets in protest; the administration used that as an excuse to nationalize the California National Guard and met the protesters not only with 2,000 guardsmen but with 700 Marines, as well.

Let’s have a show of hands: everyone who believes that there is a Constitution of the United States raise your hand. OK, good. Now everyone who believes in the Constitution of the United States raise your hand. Some of you might be thinking, “Wait. Didn’t he just ask us to do that?” Well, no. There’s a difference between “belief that” and “belief in.”

Let’s have a show of hands: everyone who believes that there is a Constitution of the United States raise your hand. OK, good. Now everyone who believes in the Constitution of the United States raise your hand. Some of you might be thinking, “Wait. Didn’t he just ask us to do that?” Well, no. There’s a difference between “belief that” and “belief in.”  One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”

One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people” “They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats.”

“They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats.” Again this week as last, our first reading today is from the First Book of Kings and like last week’s, it is a prayer spoken by King Solomon. Last week, it was a private prayer spoken in a dream late at night. Today, it is a public prayer. As long as it was, this reading is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that Solomon offered when the Temple was finished and consecrated. In it, Solomon asks an important question, “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?”

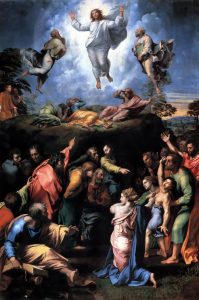

Again this week as last, our first reading today is from the First Book of Kings and like last week’s, it is a prayer spoken by King Solomon. Last week, it was a private prayer spoken in a dream late at night. Today, it is a public prayer. As long as it was, this reading is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that Solomon offered when the Temple was finished and consecrated. In it, Solomon asks an important question, “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?” Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter.

Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter. In the Episcopal Church, when we baptize a person, we pray that God will “give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will, and to persevere, a spirit to know, and love, [God], and the gift of joy, and wonder in all [God’s] works.”

In the Episcopal Church, when we baptize a person, we pray that God will “give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will, and to persevere, a spirit to know, and love, [God], and the gift of joy, and wonder in all [God’s] works.” On April 12, a little more than seven months ago, I was privileged to officiate and preach at a service of Choral Evensong at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland. Following the service, on our way home to Medina, my wife Evelyn and I stopped at a Lebanese restaurant in Middleburg Heights for a late dinner in celebration of our 43rd wedding anniversary, which that day was. After a lovely meal of hummus, baba ganoush, spicy beef kafta, and chicken shwarma, we went home to bed. A few hours later, around 2 a.m., I woke up with a horrendous case of heartburn. I took some antacid and went back to sleep sitting up in my favorite armchair. At 7 a.m. the next morning, I woke up knowing that I hadn’t had indigestion after all; I was having a heart attack.

On April 12, a little more than seven months ago, I was privileged to officiate and preach at a service of Choral Evensong at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland. Following the service, on our way home to Medina, my wife Evelyn and I stopped at a Lebanese restaurant in Middleburg Heights for a late dinner in celebration of our 43rd wedding anniversary, which that day was. After a lovely meal of hummus, baba ganoush, spicy beef kafta, and chicken shwarma, we went home to bed. A few hours later, around 2 a.m., I woke up with a horrendous case of heartburn. I took some antacid and went back to sleep sitting up in my favorite armchair. At 7 a.m. the next morning, I woke up knowing that I hadn’t had indigestion after all; I was having a heart attack. Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,”

Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,” When I was 19 years old, my parish priest, Fr. John Donaldson, died of cancer. I was privileged to be the acolyte and crucifer at his requiem and burial. It was a very formal, high-church affair. In all honesty, I remember very little of Fr. John’s funeral. I don’t remember Bishop Bloy’s homily at all, but I do remember the committal at the graveside. You see, it was my first experience of a burial using the liturgy of the Episcopal Church.

When I was 19 years old, my parish priest, Fr. John Donaldson, died of cancer. I was privileged to be the acolyte and crucifer at his requiem and burial. It was a very formal, high-church affair. In all honesty, I remember very little of Fr. John’s funeral. I don’t remember Bishop Bloy’s homily at all, but I do remember the committal at the graveside. You see, it was my first experience of a burial using the liturgy of the Episcopal Church.