Texts: 1 Samuel 3:1-10(11-20)

Psalm 139:1-5, 12-17

1 Corinthians 6:12-20

St. John 1:43-51

Sequence Hymn: I Have Decided to Follow Jesus

I spend a portion of each day in private prayer. Sometimes that happens at home in the early morning hours before Evelyn rises. Sometimes it happens late at night after she has gone to bed. Sometimes it happens in during the day when I am here in the church building. On those occasions I often come into this space, which some of you know is a very different place in the quiet of a weekday afternoon when it is empty. It is at those times that I come here alone to pray and often I find myself contemplating the stained glass windows.

Window of Hannah, Samuel, and Eli

Eli was an hereditary priest and a professional prophet at the shrine of the Lord at Shiloh. The priesthood in ancient Judaism was a family affair belonging to the descendants of Moses’ brother Aaron. Eli is one of these as are, obviously, his sons. But in the time of Eli’s priesthood, God decides it is time for things to change. Not because of anything Eli has done, in particular, but because of what his sons Hophni and Phinehas are doing.

The Jewish religion at the time was one which practiced animal sacrifice. Devotees, those wishing to obtain the Lord’s favor and those wishing to atone for sins, would bring animals from their flocks and herds to the shrine and Eli and his sons would sacrifice them on their behalf. The choicest cuts of meat were to be burned on the altar to God; the priests and their families were permitted to feed themselves, and those in need, with the less good parts. The inedible bits were also to be burnt so that nothing of the consecrated animal could be desecrated.

Eli’s sons, however, were not following the rules – they were taking the best parts of the meat for themselves – and although Eli was not doing so, he was not preventing his sons from doing so. God was not pleased, and God decided it was time for a change.

We are told right at the beginning of this story that “the word of the LORD was rare in those days” and that “visions were not widespread.” As if to underscore this point, the author tells us that Eli’s “eyesight had begun to grow dim so that he could not see.” But then Eli does “see” perfectly well what is happening when Samuel, hearing the voice of God in the nighttime, comes running to him: Eli knows very well what God is up to. God is making a change.

In the lesson from John’s Gospel we heard the story of the calling of Phillip and, through Philip, the calling of Nathanael (who is elsewhere identified as Bartholomew, son of Talemai). Nathanael is initially not terribly taken with Philip’s new-found messiah, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” he asks, but he soon changes his tune. After what seems to us, I’m sure, a brief and rather puzzling conversation, Nathanael exclaims, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” Jesus seems to be amused by this, but in his answer makes a statement that some would probably find very disconcerting: “You will see greater things than these,” he tells Nathanael the reluctant disciple, “Very truly, I tell you, you will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man.” In a word, Jesus promises Nathanael nothing less than significant and constant change.

The past two or three years for St. Paul’s Parish have been a time of change. The vestry of three years ago was approached by the owners of the two properties to the east of the church and asked if we would like to buy them. With what I believe to have been forward thinking wisdom, the vestry did so. I know that not everyone agrees with that decision; there are some who seem to agree with the feelings of a mythical late 19th Century Duke of Cambridge who is reputed to have said, “Any change, at any time, for any reason, is to be deplored.” Perhaps there are some who look back to and would hope to return to the church heydays of the 1950s. But as the hymn we just sang says, “No turning back, no turning back!” It’s not the 1950s any longer and never will be again. And the day of single-purpose church buildings is gone. That vestry three years ago knew that, eventually, this building would need to expand beyond the needs of the then-current congregation.

The vestry of two years ago in 2010 began a process of “visioning”. Seeing that we are approaching the end of the congregation’s second century of existence and looking forward to beginning a third century of ministering in Christ’s Name to the people and community of Medina, Ohio, that vestry on retreat with the Rev. Brian Suntken, rector of Christ Church, Hudson, developed action plans for changes in programs and in administrative practices, including setting in motion the process which culminated in the Parish Vision Statement. That process included inviting several members of congregation to gather for an all day retreat in July 2010 and to participate in follow up sessions leading to adoption of a statement which clearly lays out mission: “Our reason for being is to set hearts on fire for Jesus Christ.” It describes our vision of a parish which is dedicated to “advancing the Kingdom of God through vibrant and exciting liturgy and worship, social justice ministries, promotion of the arts, and support of education.” This mission and vision have been articulated in our Sunday prayers ever since.

This understand of our mission and vision are quite a bit more dynamic than the parish’s previous mission statement, a statement which said merely that we would welcome those who came to join us and which know one could remember ever having actually been adopted by the congregation! At some point in the past, it simply appeared on the bulletin. Nonetheless, there were some who expressed unhappiness with the change. After all, “Any change, at any time, for any reason, is to be deplored.”

Living into that mission and vision, the leadership of the parish realized that this building complex, as lovely and as loved as it is, needed to be changed and over the past six months the vestry and a committee appointed by them, the Inviting the Future Committee, have sought to make the case and solicit your support, including your financial support, for that change. We have listened carefully to your feedback, as we hope you have listened with equal care to reasons for this effort.

The change at Shiloh could not have been easy for Eli. He nonetheless embraced it: he said, “It is the LORD; let him do what seems good to him.” By no stretch of the imagination does your parish leadership pretend to be God. But like Eli we believe that change is inevitable, that change is constant, and that when embraced in the right spirit change can be positive and productive. It is our hope and prayer that the changes we are seeing at St. Paul’s Parish will be positive and productive.

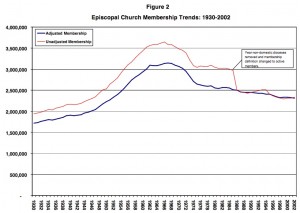

As much as some of us might wish there were no changes being made, the truth is that change is inevitable and it is always in one direction. Time moves forward into the future; it never stands still and it certainly never runs backward to the past. “No turning back, no turning back!” Times change. Fashions changes. Prices change. Technology changes. People change. Change happens. It’s part of life — a biologist would say that change is life; for a living entity — and rest assured, the church IS a living entity — for a living entity to cease to change is to die.

As I said before, the day of the single-purpose church buildings is gone. All around us we see the evidence of that and we see what happens to communities who have tried to hang on to that model. I have been in the Diocese of Ohio for 8-1/2 years and during that time we have declared fifteen parishes extinct; as our convention delegates know, we declared three parishes extinct this year! I have served on the board of trustees of the diocese for nearly three years and in that time we have sold five church buildings at bargain basement prices. I do not want to see that happen at St. Paul’s, Medina, and I’m sure no one here does either!

And so today, here at St. Paul’s Church, we are going through, as in fact we always have, a time of change. If most of us could have our way, even those of us most involved in these changes, we would have to admit that we would be most comfortable if things would just stay the way they have always seemed to have been. We have been comfortable with the way things were. We have felt secure with the way things have been. But change, no matter how much it may be deplored, is inevitable and irreversible. “No turning back, no turning back!” The question is not if change will happen; it is how it will happen. Change is inevitable, but we have a choice to either be proactive, manage change, and make it positive and productive, or to be reactive, have no say in it, and suffer from it.

The early 20th Century philosopher of change, Henri Louis Bergson, suggested the illustration of a summer day.

We are stretched on the grass, [he said] we look around us — everything is at rest — there is absolute immobility — no change. But the grass is growing, the leaves of the trees are developing or decaying — we ourselves are growing older all the time. That which seems at rest, simplicity itself, is but a composite of our ageing with the changes which takes place in the grass, in the leaves, in all that is around us. [The Nature of the Soul, four lectures delivered at the University of London, October, 1911, lecture 2]

Change happens everywhere and at all times. Everything is changing. Nothing in this world ever stays the same.

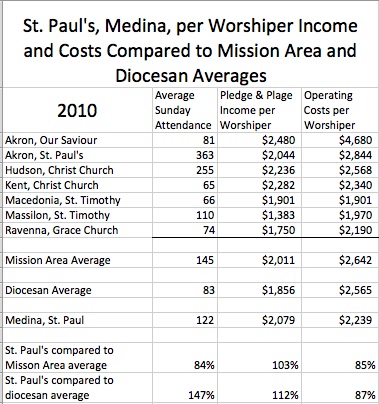

The annual journal which will be given to you at the business session this morning includes spreadsheets reporting changes in parish statistics, the budget and performance financial statements for the past year, the budget for the coming year, and the changes in our financial position from the beginning of 2011 to its end. Yes, there are deficits and yes, those deficits are large. We had not quite $60,000 less in the bank on December 31 than we did the preceding January 1. About 29% of that decrease was planned in the budget for last year; we knew we would have to spend from savings as we have done for many years. About 8% of that decrease is a result of market forces; our investments are simply worth less now than they were before. The remaining 53% was spent on the Inviting the Future process and will be paid back to our operating savings out of the proceeds of the capital campaign. Some will, I know, view that deficit simply as a loss (and certainly those market value changes are that for the parish as I know they have been for all of us who have investments), but I would encourage you to view most of it as an investment in the future, an investment I believe will pay dividends of growth and vitality.

Our anticipated pledged income for the coming year is nearly identical to that which was pledged in 2011, around $220,000. But keep in mind that in addition to that, our membership has also pledged gifts to the Inviting the Future Capital Campaign which now exceed $300,000 over the next five years. That, I believe, demonstrates great commitment to the future of St. Paul’s and the directions we are moving.

Our parish statistics already show in 2011 that we are beginning to grow. Although you will see that our average Sunday attendance appears to be smaller than in 2010 by about 5%, I would ask you to remember that we held three services each Sunday in 2010 and only two each Sunday during most of 2011; in truth our Sunday morning attendance has increased on average. Our Easter Sunday attendance was slightly higher and our Christmas attendance was larger by nearly 14%. Private eucharists, which are primarily our lay eucharistic visits, increased by 72%.

In our registered membership (which I hasten to admit is a far different thing from active membership) we experienced a net increase in 2011 of about 3%. That’s not huge, I admit, but it is growth. There were six confirmations in 2011 compared to four the year before, and there were ten baptisms compared to only three in 2010. Three of those baptisms were of adults. If you took part in studying one of the Unbinding Series books (either Unbinding the Gospel or Unbinding Your Heart) you may recall that the author’s definition of an exceptionally vibrant parish was one in which there were at least five adult baptisms. With three in one year, I suggest to you, that we are moving in the direction of great vibrancy. All of these figures show change that is positive and productive.

“Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree?” Jesus asked Nathanael in our Gospel lesson this morning. Then he told him, “You will see greater things than these.” These words of promise are only spoken to and meant only for Nathanael; the “you” in this declaration is the Greek singular. But the final verse brings to completion the invitation and promise of the first words of Jesus in the Gospel of John. Those first words are a question not only to Jesus’ first followers, but to every reader or hearer of the Gospel of John: “What are you looking for?”

Now, after his private conversation with Nathanael, Jesus opens the discourse to include all those around them, and you and me and all readers of this Gospel: regardless of what we may have come looking for, “Very truly, I tell you [plural], you [plural] will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man.” Jesus is recalling to us Jacob’s vision of a ladder stretching from earth to Heaven on which a constant parade of angels climbed up and down. The Jewish Biblical philosopher Philo said the angels in Jacob’s vision represent the continually changing affairs of men. The 4th Century Christian saint, Gregory Nazianzan, believed the angels of Christ’s promise are meant to signify that we will all take steps towards improvement and excellence, that we are always changing, always moving forward following Jesus. Regardless of what we may have come looking for, what we have found and will continue to find is change, change in the world around us and change in ourselves. “No turning back!”

This is the promise of the Gospel of John for all! This is the promise of Christ for all! This is the promise of God for God’s people here at St. Paul’s Parish. Change, inevitable change, positive and productive change, leading to improvement and excellence, advancing the kingdom of God, and setting hearts on fire for Jesus Christ.

Let us pray:

O God of unchangeable power and eternal light: Look favorably on St. Paul’s Parish and on your whole Church, that wonderful and sacred mystery; by the effectual working of your providence, carry out your plan of salvation; let the whole world see and know that all things are constantly changing, that things which were being cast down are being raised up, that things which had grown old are being made new, and that all things are being brought to their perfection by him through whom all things were made, your Son Jesus Christ our Lord; who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. (Adapted from a prayer in the Episcopal Ordination service, BCP 1979, page 528)

Over the past ten days or so I have been required almost every day to visit one of our larger local grocery stores, one which has a center section devoted to seasonal merchandise. On each visit as I walked through that section, one item on a top shelf kept catching my attention, but each time I declined to buy it. Every day I would go away and wonder why I was attracted to that particular thing, and those contemplations made their way into my notes for this homily.

Over the past ten days or so I have been required almost every day to visit one of our larger local grocery stores, one which has a center section devoted to seasonal merchandise. On each visit as I walked through that section, one item on a top shelf kept catching my attention, but each time I declined to buy it. Every day I would go away and wonder why I was attracted to that particular thing, and those contemplations made their way into my notes for this homily.  Dear Patrick,

Dear Patrick,  What would you do if the world were to end tomorrow? That’s a good question to be thinking about as we consider our lesson from Mark’s Gospel; that’s a good question to be thinking about as we contemplate baptizing these two boys today. In today’s Gospel reading, Jesus is warning his disciples about the end of time, and the picture he paints is not pretty:

What would you do if the world were to end tomorrow? That’s a good question to be thinking about as we consider our lesson from Mark’s Gospel; that’s a good question to be thinking about as we contemplate baptizing these two boys today. In today’s Gospel reading, Jesus is warning his disciples about the end of time, and the picture he paints is not pretty: