====================

On the Seventh Sunday of Easter: the Sunday after the Ascension, June 1, 2014, this sermon was offered to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Acts 1:6-14; Psalm 68:1-10, 33-36; 1 Peter 4:12-14, 5:6-11; and John 17:1-11. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

‘Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.(From And Still I Rise,Maya Angelou, Random House:1978.

Note — The verse beginning “Does my sexiness upset you?” was not read in church.)

The late Dr. Maya Angelou, who died this week and was (in my opinion) one of the greatest of contemporary English-language poets, wrote that poem (entitled Still I Rise) in 1978. Though it speaks out of her experience as a black woman growing up in the segregated South of the mid-20th Century, I believe it also speaks to us in our context today, celebrating the Ascension of Christ into heaven and, also, honoring our five newly minted high school graduates.

The Feast of the Ascension was Thursday. You may have missed it, however; it is a feast largely ignored by the Church. It passes by and we seldom, if ever, give any thought to it. In the Sunday rota it is noted only as the day after which the Seventh Sunday of Easter comes: that’s exactly how today’s collect is titled in The Book of Common Prayer, Seventh Sunday of Easter: The Sunday after Ascension Day. Kind of sad, because the Ascension really is the last event of the Incarnation, the last scene of the last act of the great drama which is “the Christ event.” Fortunately, this year (Year A of the Revised Common Lectionary) we have actually heard the story of the Ascension from the Book of Acts. This is not the case in the other two years of the rotation; in years B and C the Ascension isn’t even mentioned in any of the Sunday readings.

The story of Christ’s Ascension is told not only in Acts, which we heard this morning, it is also found in the Gospels of Mark and Luke. Mark’s account is brief, a single verse: “So then the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God.” (Mk 16:19) Luke’s is also short: “He led them out as far as Bethany, and, lifting up his hands, he blessed them. While he was blessing them, he withdrew from them and was carried up into heaven.” (Lk 24:50-51).

Although neither Matthew’s Gospel nor John’s mention the Ascension event itself, both include prophetic references to it. According to Matthew, in his trial before the High Priest just before his Crucifixion, Jesus said, “I tell you, from now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven.” (Mt 26:64) In John’s Gospel, after the Resurrected Jesus tells Mary Magdalene not to cling to him, he gives her a message for the Apostles: “Go to my brothers and say to them, ‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.'” (Jn 20:17) So the fact of Jesus’ Ascension is well attested by Christian Scripture.

This Jesus, whom the powers of his age had (to use Dr. Angelou’s poetic language) tried to “write down in their history with bitter, twisted lies,” had tried to “tread in the very dirt” — this Jesus rose, not only from the grave into a new earthly existence, but into heaven. This Jesus, whom they “wanted to see broken, with bowed head and lowered eyes, with shoulders falling down like teardrops, weakened by his soulful cries” — this Jesus rose into very center of the Godhead. This Jesus, whom they “killed with their hatefulness” rose “out of the huts of the Hebrews’ history of shame,” from Israel’s past, a past “rooted in pain,” “bringing the gifts that his ancestors gave;” he is “the dream and the hope” of every human being enslaved to sin and death. He is our hope and he rose. He ascended into heaven taking our humanity into the very presence of God Almighty.

If the Incarnation (meaning the whole of Jesus’ earthly being, the entire time of God’s being in the flesh on earth) were viewed as a stage play, the drama of salvation would be seen in this way:

Act One — In the Nativity, God becomes a human being offering great promise to humankind.

Act Two — In the life of Jesus, God fully enters human existence in all its aspects making clearer the meaning of the promise.

Act Three — In the death and resurrection of Jesus, God defeats death and opens the way of eternal life to all human beings setting the scene for fulfillment of the promise.

Act Four — In the Ascension, the story comes full circle as a human being becomes God bringing the promise of the Nativity to fruition.

(Pentecost and all that follows it are the epilogue, just as the story of Israel and the words and works of the Prophets are the prologue.)

The Ascension is the denouement of the entire story but, unfortunately, most of the audience, thinking the play concluded, left after Act Three; some may even have left in the middle of that act. The climax of the drama played out on Thursday to a largely empty theater.

One of the Episcopal Church’s collects for today says: “We believe your only-begotten Son our Lord Jesus Christ to have ascended into heaven, so we may also in heart and mind there ascend.” (BCP 1979, page 226) I think this prayer gets it slightly wrong. Our ascension with Jesus is not a future thing that we “may” later attain. Rather, in Jesus’ Ascension we all have already ascended. It is not only Christ’s humanity but our humanity that ascended into heaven. God has already seated us in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus; our ascension is not so much an experience to be attained, but a reality to be experienced. As St. Athanasius famously put it, “God became man that man might become God.” This is known theologically as the theosis or deification of humanity, and in the Ascension of Jesus it has already happened.

So here we are, deified human beings capable, as Jesus told us, of doing the very works that he did and, in fact, of doing greater works because he has ascended to the Father and he will do whatever we ask in his name — at least that’s what he promised in the Gospel lesson from John we heard in church two weeks ago (Jn 14:12-13) — but do we actually do them? Do we do the works of power and witness to the truth of the Gospel? Let’s be honest and admit that we usually don’t.

We don’t because we’re a lot like the eleven guys standing on that hilltop in Bethany “gazing up toward heaven.” Like them, as Prof. James Holbert of the Perkins School of Theology has written, “We are too enamored of the ascending Jesus, our necks strained as we peer upward, hoping for a further sign, for a magic act, for a cloud spelling out ‘I love you.'”

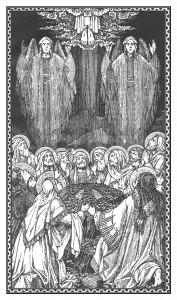

It’s my favorite part of the story, really, because it demonstrates just how human the Apostles really were, how much like us. It’s this part of the story that is depicted in the woodcut on the cover of our bulletins. There they are looking up, Jesus’ feet just disappearing, when the “two men” (probably angels) appear and ask them why they are staring into space. In our modern vernacular, the two angels tell them, “Don’t just stand there. Do something!”

It’s my favorite part of the story, really, because it demonstrates just how human the Apostles really were, how much like us. It’s this part of the story that is depicted in the woodcut on the cover of our bulletins. There they are looking up, Jesus’ feet just disappearing, when the “two men” (probably angels) appear and ask them why they are staring into space. In our modern vernacular, the two angels tell them, “Don’t just stand there. Do something!”

Prof. Holbert paraphrases and analyzes what the angels say in this way:

“Why do you stand looking into heaven?” Did you not pay attention to him just a few moments ago? He said, ‘Go,’ and you are rooted on this spot, looking longingly for some further word from him. He will come back in the same way that he went, but you need ask no further questions about when, they imply. “When” is simply not the right question to ask.

Why in heaven’s name (I mean that quite literally!) do so many Christians then spend vast amounts of time, inordinate amounts of energy, immoderate amounts of speculation, asking precisely that very question? We have been asked to be “his witnesses” to the world, not his calculators for his return. It remains a thorough mystery to me why this is so, and has been so throughout Christian history.

But I suppose I do know the answer. It is far safer, far less demanding, to be a speculator than a witness. Speculators write books of calculations, hold seminars that attract thousands, rake in untold piles of loot, while prognosticating a certain time for Jesus’ return. Witnesses, on the other hand, just witness to the truth of the gospel: the truth of justice for the whole world, the love of enemies, and the care for the marginalized and outcast. As Acts 1 makes so clear, the world needs far fewer speculators and far more witnesses. (Speculators or Witnesses)

Which brings me to our five high school graduates . . . . You have finished that part of your education which society has made mandatory. Whatever you do from now on is up to you. You may, if you and your families decide, continue your education at college or university; you may continue it in trade or vocational school; you may continue it as an apprentice in a skilled trade. You may, alternatively, decide to enter the work force immediately and skip any further formal education and training, opting instead for what is known as “on the job training.” And you could, although no one here would recommend it or be happy if you did so, opt to do none of these things and, instead, become a bum, a grifter, a burden on society, in which case you will learn the hard and dangerous lessons of the streets.

Whatever you choose to do, you may have noted that every path means continuing to learn. I hope, as I’m sure everyone here and your parents hope, that you will learn the lessons of faith, hope, and love.

We hope that you will learn the lessons that Dr. Angelou learned and tried to teach us through her poetry — if people tell lies about you, rise above it; if people try to tread you in the dirt, rise above it; if they want to see you broken and weeping, disappoint them and rise above it; if they try to shoot you with their words, cut you with their eyes, or kill you with their hatefulness, rise above it.

We hope that you will learn to be, as Prof. Holbert said, witnesses “to the truth of the gospel: the truth of justice for the whole world, the love of enemies, and the care for the marginalized and outcast,” that you will learn to be (as the Letter of James puts it) “doers of the word, and not merely hearers.” (James 1:22)

That is our hope for you and our prayer.

And now I have a word for the parents of our graduates. I’ve been where you are now, twice. When our eldest, our son Patrick, entered college he went away to the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. We drove him down to Sewanee and, with other freshman parents, we attended a meeting with the school’s president while our children took part in orientation activities. At the end of our meeting, the president was quite blunt: he basically said, “Go away. Get off campus. Let go of your sons and daughters.” Like Mary Magdalene, we were being told not to cling, not to hold on. So we left that meeting, found our son, and said good-bye. After he hugged us both, he turned and walked down the street toward to his dormitory, and he never looked back.

I stood there watching him go and, like those guys on the Mount of Olives, I wanted him to look back; I was “hoping for a further sign, for a magic act, for a cloud spelling out ‘I love you.'” Like them, I didn’t get it. I suppose the Apostles realized at some point as they stared into the sky that their friend, their rabbi, was no longer the man they thought they knew; he was something more. He was, and is, God. Standing on that campus lane at Sewanee, I knew that this young man was no longer the child I thought I knew; he was something more. He was, and is, an adult.

Both of our children, Patrick and Caitlin, are adults. So are yours. I’m proud to say that both of ours are college graduates and, though Caitlin is not working in her chosen field (yet), both are fully employed, productive members of society. So will yours be.

So don’t cling to them and don’t just stand there watching them go away, fading into the distance. You have things to do because, like them, like those eleven guys on that hillside in Bethany, like everyone of us, you too are called to be witnesses “to the truth of the gospel: the truth of justice for the whole world, the love of enemies, and the care for the marginalized and outcast,” to be “doers of the word.”

So graduates, parents of graduates, everyone . . . Remember the implication of the angels at the Ascension.

Don’t just stand there. Do something!

Experience the reality of the Ascension. Christ’s Ascension, our Ascension, your Ascension!

Rise!

Rise!

Rise!

Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Leave a Reply