====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Sixth Sunday after Pentecost, July 16, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are from Proper 10A (Track 1) of the Revised Common Lectionary: Genesis 25:19-34; Psalm 119:105-112; Romans 8:1-11; and St. Matthew 13:1-9,18-23. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

This is an old and familiar story, a comfortable story if you will … the parable of the sower. We’ve all heard it before and we know what it means; we know the four types of soil and we know where we fit into the picture the story paints. It helps that Jesus takes the time to explain it to his disciples (there are some verses edited out of our lectionary version of the Gospel lesson so as we heard it this morning this isn’t clear, but the situation is that Jesus tells the parable in public to the crowds on the beach near Capernaum, then later offers the explanation in private to the Twelve).

The parable, Jesus says, represents the variety of responses to the good news of the kingdom of heaven. Although we call it the parable of the sower, Jesus focuses his explanation on the types of soil into which the sower’s seed is cast. That “soil,” Jesus explains, is the human heart. In ancient Israel, the heart was thought to be the seat of personality; in one’s heart was where a person knew things, thought, decided, exercised one’s will, and acted; it was the center of human commitment; it directed one’s way of life.

The seed that falls on the path, said Jesus, represents those who hear the good news but do not understand it. Because of the hardness or dullness of their hearts, the evil one, who resists God’s purposes snatches it away. It is not clear, in the parable or in Jesus’ explanation, why the devil seems to be more powerful in influencing the human heart than is God’s word, but then that is not the point of the parable. That, perhaps, is a teaching Jesus meant to leave for another day.

The second response to the word of God is that of the person who readily receives it but does not endure as a disciple. This sort is represented by the seed that falls on the rocky ground and sprouts quickly but dies under harsh conditions. The presence of “trouble or persecution [that] arises on account of the word,” which Jesus has promised as the inevitable result of discipleship, causes the person to fall away. Because the values of God’s kingdom threaten and are at odds with dominant culture’s values and structures, the world “strikes back” and this sort of person cannot resist or survive the onslaught.

The seed that fall among the thorns and is choked by the weeds represents the third sort of response. This person, says Jesus, is the who hears but “the cares of the world and lure of wealth choke the word” so that it cannot flourish and bear fruit. Concerns of daily life or the lure of material gain and worldly success prevent God’s rule from breaking through and nourishing new life. As a result, the good news yields nothing.

And then there is the seed sown on good soil, those who hear and understand the word. We know who these good people are, don’t we? These are those like ourselves, whose hearts are pure and who embrace the good news, who fight off the devil, who endure difficulty and persecution, who do not define themselves in terms of worldly success and wealth. Right? These are the good people who are the good soil where the seed of God’s grace sprouts and grows and bears fruit.

Well, not really. For the past few weeks we have been reading the stories of the first family to hear the word of God’s reign, the first family to be invited into a kingdom covenant with God: Abraham and Sarah, their son Isaac and his wife Rebekah, and now today we hear about their sons Esau and Jacob. This family represents the soil in which the good news of God’s love was first planted eventually bore the fruit of the People of Israel.

Yes, eventually Abraham trusted in the Lord and it was accounted to him as righteousness, but initially Abraham and Sarah did not trust the Lord, so they used and then discarded Hagar the handmaiden, nearly killing her and Ishmael her son after Sarah finally birthed a son of her own, and that son, Isaac, Abraham also came close to killing. As for Isaac, about the only active things he is seen doing in the whole story of the family other than tending sheep, weeping when his mother dies, and then eventually burying his father, is move the family to Gerar during a time of famine and, in doing so, lie to King Abimilech about who Rebekah is. Otherwise, Isaac is portrayed as excessively passive. He allowed himself to be nearly sacrificed with no word of complaint; he accepted a wife selected for him by his father’s slave; and late in life he is cheated and hoodwinked by his wife and her favored son. And that son, Jacob, is a trickster and a cheat.

We learn in our Old Testament lesson today that Jacob and his brother Esau were twins who wrestled in their mother Rebekah’s womb, causing her great distress. Esau is born hairy and red, characteristics that link him to the people of Edom, whom tradition claims to be his descendants.

Esau turns out to be strong, comfortable in the wilderness, and skillful at hunting. Jacob is the second-born of the twins, but he is destined to be the ancestor of the 12 Israelite tribes. He is smooth-skinned and fair. When the twins are born, Jacob comes out with his hand around his brother’s foot. This detail foreshadows that Jacob will upset Esau’s status as the firstborn son and subvert the social customs and expectations that would favor the elder son.

His name, Jacob or “Ya’aqov” in Hebrew, is believed to be derived from the word ‘aqav, meaning “heel,” or from the similar word ‘aqov meaning “to trick” or “to cheat.” If the latter, today’s story of his bargaining for the firstborn’s birthright certainly illustrates its appropriateness. If the former, it is a pun which “works in English as well as in Hebrew. Jacob is indeed something of a ‘heel.’ He is a trickster, a man who schemes and plots, always looking for the advantage; in these chapters [of the Abrahamic family story], the advantage particularly over his twin brother Esau.” (Schifferdecker, Working Preacher, 2017)

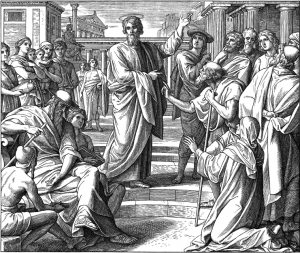

Today’s reading from the Hebrew Scriptures is only half of the story of the cheating of Esau. On the cover of our bulletins this morning is a painting by an unknown artist of the 17th Century. It’s interesting to me that it purports to illustrate the story we heard this morning, but includes in it not only Esau and Jacob, but also Rebekah. Rebekah is not described in the text as being present, but in the painting she is artistically the most significant figure; she is the one on whom most of the light falls. This is because the artist is conflating this part of the story, in which Jacob firstborn’s birthright, with its conclusion, in which Rebekah (who scripture says favored Jacob) aids her younger son in tricking Isaac into giving him also the firstborn’s blessing. Jacob is not the only trickster and cheat in the family.

My point is that this family, from Abraham and Sarah through Isaac and Rebekah to Jacob, are not really people we would describe as pure in heart, or as those who endure difficulty and hardship with forbearance and fortitude, or as those we would expect to fight off the devil. But, nonetheless, they are the “good soil” in which the kingdom of heaven took root, eventually flourished, and produced the People of God.

So who are those folks whom Jesus, generations later, would call “the good soil”? “Who are those ‘who hear the word and understand it, who indeed bear fruit’ and yield an abundant harvest? In Matthew’s story it seems they are the least likely ones. Jesus tells the chief priests and elders, ‘the tax collectors and the prostitutes are going into the kingdom of God ahead of you’ (21:31-32). In the parable of the sheep and the goats, the righteous bear fruit by serving the ‘least of these,’ and even they are surprised to find that they have been serving Jesus (25:34-40).” (Johnson, Working Preacher, 2011)

Here’s the thing about soil – it isn’t good on its own. The soil that is beaten down under foot along the path can’t, by its own effort, become good soil. The soil that is rocky and shallow cannot make itself deep and rich. The soil that is thorny and choked with weeds can’t clear itself of those unwanted plants. And the soil that is good can’t claim that it is good by its own virtue.

In Alcoholics Anonymous and other Twelve Step programs, the first step is to admit that one is powerless over ones addiction, over the thing or things that have made a mess of one’s life. The second step is to accept the reality of a Higher Power, and the third is to turn one’s will and life over to God. I often think that in the New Testament there are three people whom Jesus either talks about or encounters who exemplify these steps. One is the tax collector who went to the temple to pray a simple prayer: “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” (Lk 18:13) The second is the widow who also went to the temple and who “out of her poverty [contributed] everything she had, all she had to live on.” (Mk 12:44) The third is the woman denounced as a sinner who bathed Jesus’ feet with her tears and dried them with her hair. (Lk 7:38)

These people are the powerless soil, the “good soil,” in which the word of God, the good news of the kingdom of heaven, takes root and grows. The soil is not good by any worldly definition of “good”. These are not people who are pure in heart; these are not people who have lived blameless lives; these are not people who respected for their faith, their position in the community (secular or religious), or their success (by whatever measure may be applied).

The soil is good not by any virtue of its own, but because the sower cares for and works with the soil, and then sows abundantly. Abraham and Sarah are not very good people; they treated Hagar and Ishmael and even Isaac very badly, yet Scripture tells us that Abraham trusted in the Lord and it was accounted to him as righteousness. Isaac was a passive man victimized and cheated by his own family, yet he redug his father’s wells and received God’s blessing. Rebekah and her second-born son Jacob coveted and eventually received the birthright and the blessing of the firstborn, but only because they cheated his brother and hoodwinked his father. They were not particularly good! None of them! As portrayed in the Hebrew Scriptures, Abraham and his family were deeply flawed human beings, yet they were the recipients of the Covenant. It took generations of the Lord’s attention and care for the descendants of Abraham to bear fruit.

And Jesus put his effort into disciples who looked similarly unpromising. “He squandered his time with tax collectors and sinners, with lepers, the demon-possessed, and all manner of outcasts.” (Johnson, Working Preacher, 2011) Yet his work with and among such as these yielded the fruit of the Church.

God’s work with the Abrahamic family, Jesus’ work with the outcasts of his generation, was like that of which the Psalmist sings:

You visit the earth and water it abundantly;

you make it very plenteous;

the river of God is full of water.

You prepare the grain,

for so you provide for the earth.

You drench the furrows and smooth out the ridges;

with heavy rain you soften the ground and bless its increase.

(Ps 65:9-11; BCP 1979, page 673)

The parable of the sower is an old story, a comfortable story, and we know where we fit into it. Or perhaps we don’t. We like to think we’re the “good soil,” but we are more likely the trampled down ground of the path, the rocky soil, or the patch filled with thorns and weeds. If we would be good soil, we must admit that we cannot do so of your own accord.

As the story of the first family invited into covenant with God makes clear, the soil is not good of its own virtue; it is the work of the sower that makes it good. The seed does not flourish because of the soil. The soil flourishes because of the seed.

(Note: The illustration is “Jacob offers a dish of lentels to Esau for the birthright” by an unknown 17th century artist after Gioacchino Assereto (1600 – 1649), it hangs in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.)

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

The great Anglican preacher Herbert O’Driscoll begins his reflections on our Old Testament lesson, the story of the testing of Abraham and the binding of Isaac, truthfully the near-murder of Isaac, with these words:

The great Anglican preacher Herbert O’Driscoll begins his reflections on our Old Testament lesson, the story of the testing of Abraham and the binding of Isaac, truthfully the near-murder of Isaac, with these words:

This is “Trinity Sunday,” the only Sunday of the Christian year dedicated to a truly puzzling Christian doctrine, the peculiar Christian notion that God is one-in-three and three-in one. The late Jim Griffiss, the seminary professor with whom I studied systematic theology, once quipped that one could walk into any church on Trinity Sunday and hear heresy preached; that’s because there is no good or easy way to explain this doctrine. There’s also no way to really understand this doctrine as a matter of intellectual assent. But as a friend of mine said recently, “We [are called to] worship one God in Trinity, not understand one God in Trinity. Accept the Mystery, sing the Te Deum, and move on.” (Facebook discussion) I think he’s right. As a way of describing God, one must admit that the doctrine of the Trinity seems paradoxical, more than a little bit ambiguous, and frankly beyond explanation in a short (or even a long) sermon. So, we won’t be singing the Te Deum today, but I would like to use some poetry to explore how we can experience and worship the Triune God.

This is “Trinity Sunday,” the only Sunday of the Christian year dedicated to a truly puzzling Christian doctrine, the peculiar Christian notion that God is one-in-three and three-in one. The late Jim Griffiss, the seminary professor with whom I studied systematic theology, once quipped that one could walk into any church on Trinity Sunday and hear heresy preached; that’s because there is no good or easy way to explain this doctrine. There’s also no way to really understand this doctrine as a matter of intellectual assent. But as a friend of mine said recently, “We [are called to] worship one God in Trinity, not understand one God in Trinity. Accept the Mystery, sing the Te Deum, and move on.” (Facebook discussion) I think he’s right. As a way of describing God, one must admit that the doctrine of the Trinity seems paradoxical, more than a little bit ambiguous, and frankly beyond explanation in a short (or even a long) sermon. So, we won’t be singing the Te Deum today, but I would like to use some poetry to explore how we can experience and worship the Triune God. As my parishioners know, I often find the images invoked by poets comforting and illuminating in times of grief.

As my parishioners know, I often find the images invoked by poets comforting and illuminating in times of grief. Almighty God, on this day you opened the way of eternal life to every race and nation by the promised gift of your Holy Spirit who empowered the disciples to proclaim the Good News to peoples from many lands speaking many tongues: we now pray for those in many lands speaking many languages who have been hurt or killed by terrorist violence in the past fortnight in: London (England), Kabul (Afghanistan), Mosel (Iraq), Minya (Egypt), Khost (Afghanistan), Mastung (Pakistan), Gao (Mali), Borno State (Nigeria), Raqqa (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia), rural Colombia, Manila (Philippines), Baghdad (Iraq), Basra (Iraq), Portland (Oregon, USA) and Manchester (England). May God grant eternal rest to the departed, healing to the injured, and comfort to those in grief. And since Jesus taught us to love and pray for our enemies, we pray also for those who have committed these violent acts, and for those who may be contemplating additional violence. May God change their hearts and shed abroad the gift of peace throughout the world by the preaching of the Gospel, that it may reach to the ends of the earth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Almighty God, on this day you opened the way of eternal life to every race and nation by the promised gift of your Holy Spirit who empowered the disciples to proclaim the Good News to peoples from many lands speaking many tongues: we now pray for those in many lands speaking many languages who have been hurt or killed by terrorist violence in the past fortnight in: London (England), Kabul (Afghanistan), Mosel (Iraq), Minya (Egypt), Khost (Afghanistan), Mastung (Pakistan), Gao (Mali), Borno State (Nigeria), Raqqa (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia), rural Colombia, Manila (Philippines), Baghdad (Iraq), Basra (Iraq), Portland (Oregon, USA) and Manchester (England). May God grant eternal rest to the departed, healing to the injured, and comfort to those in grief. And since Jesus taught us to love and pray for our enemies, we pray also for those who have committed these violent acts, and for those who may be contemplating additional violence. May God change their hearts and shed abroad the gift of peace throughout the world by the preaching of the Gospel, that it may reach to the ends of the earth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. As I read our lessons for today and again as I heard them this morning, two verses in particular have leapt out at me. One from the Gospel of John in which Jesus says: “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3) The other is from the story in the Book of Acts in which, after Jesus has been lifted up and a cloud has taken him out of the apostles’ sight, two suddenly-appearing “men in white robes” (angels, one presumes) ask the apostles, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” (Acts 1:11)

As I read our lessons for today and again as I heard them this morning, two verses in particular have leapt out at me. One from the Gospel of John in which Jesus says: “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3) The other is from the story in the Book of Acts in which, after Jesus has been lifted up and a cloud has taken him out of the apostles’ sight, two suddenly-appearing “men in white robes” (angels, one presumes) ask the apostles, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” (Acts 1:11) If you have seen Avatar, you know that the human character Jake Sully is a disabled Marine; he is confined to a wheelchair in his “real” human life. But his avatar, a synthetic body into which his conscience is temporarily transferred, is a fully functional Na’Vi male body. At the end of the movie, after Jake has rebelled against his superiors and championed the Na’Vi’s cause against Pandora’s exploitation by Earth, Jake’s crippled body is trapped in a damaged mobile laboratory. Neytiri finds him, breaks into the lab, and rescues him: “In the end, the real Jake is not his avatar. The real Jake is a man, unshaven and unkempt, without functional legs. And Neytiri sees this. As she holds the dying Jake, she tells him ‘I see you.’ This is what love is. Love is not trying to change the other person, to make them perfect, or to focus on their weaknesses. Love is seeing a person for who they are and embracing that person.” (

If you have seen Avatar, you know that the human character Jake Sully is a disabled Marine; he is confined to a wheelchair in his “real” human life. But his avatar, a synthetic body into which his conscience is temporarily transferred, is a fully functional Na’Vi male body. At the end of the movie, after Jake has rebelled against his superiors and championed the Na’Vi’s cause against Pandora’s exploitation by Earth, Jake’s crippled body is trapped in a damaged mobile laboratory. Neytiri finds him, breaks into the lab, and rescues him: “In the end, the real Jake is not his avatar. The real Jake is a man, unshaven and unkempt, without functional legs. And Neytiri sees this. As she holds the dying Jake, she tells him ‘I see you.’ This is what love is. Love is not trying to change the other person, to make them perfect, or to focus on their weaknesses. Love is seeing a person for who they are and embracing that person.” ( A couple of years ago Pope Francis made a cogent observation about praying for those who are hungry: “You pray for the hungry. Then you feed them. That’s how prayer works.” (

A couple of years ago Pope Francis made a cogent observation about praying for those who are hungry: “You pray for the hungry. Then you feed them. That’s how prayer works.” ( It’s the Fourth Sunday of Easter and that means it’s “Good Shepherd Sunday.” And that means that clergy throughout the church have, for the last week, been scratching their heads thinking, “This again? What can I do this time with the sheep-and-shepherd simile?” But, I’m not among them. For three days this past week, the clergy of this diocese have been in conference with our bishop, with a retired seminary president, and with a retired cathedral dean exploring exactly what we understand our ordinations to the diaconate and to the presbyterate to mean. That has kind of taken my attention off the “Good Shepherd” metaphor.

It’s the Fourth Sunday of Easter and that means it’s “Good Shepherd Sunday.” And that means that clergy throughout the church have, for the last week, been scratching their heads thinking, “This again? What can I do this time with the sheep-and-shepherd simile?” But, I’m not among them. For three days this past week, the clergy of this diocese have been in conference with our bishop, with a retired seminary president, and with a retired cathedral dean exploring exactly what we understand our ordinations to the diaconate and to the presbyterate to mean. That has kind of taken my attention off the “Good Shepherd” metaphor.