For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.[1] The premise is that the ancient gods of Greece are still with us, immortal but relatively powerless beings blending into the human world around them. The story is set in current-day New York City where the goddess Artemis, mistress of the hunt and twin sister of Apollo, lives and works as a private detective. As the novel opens, Selene (as Artemis is called) and her partner Theo, a professor of classics at Columbia University, are consulting with the NYPD about a bizarre murder. What they know, and the police don’t, is that the victim is Hades, god of the underworld.

For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.[1] The premise is that the ancient gods of Greece are still with us, immortal but relatively powerless beings blending into the human world around them. The story is set in current-day New York City where the goddess Artemis, mistress of the hunt and twin sister of Apollo, lives and works as a private detective. As the novel opens, Selene (as Artemis is called) and her partner Theo, a professor of classics at Columbia University, are consulting with the NYPD about a bizarre murder. What they know, and the police don’t, is that the victim is Hades, god of the underworld.

This is the first death of an immortal god in millennia and the rest of the gods are thrown into turmoil. They have to join forces and work together to solve the murder before another one of them killed. This is difficult because if the Greek gods are nothing else they are a dysfunctional family. After all, they are all descended from Kronos, the divine son of Uranus, the sky, and Gaia, the earth. Kronos overthrew his parents and ruled during the mythological Golden Age. He married his sister Rhea and fathered several children, but prevented strife by eating then as soon as they were born. Eventually, Rhea grew tired of this and tricked Kronos into not devouring Zeus, who overthrew Kronos and cut open his father’s belly and freed his brothers and sisters.[2]

As a theologian and a preacher, I am very glad I don’t have that mythology to deal with on a weekly basis! Finding something good to preach based on the stories of that dysfunctional family would be a task I don’t think I’m up to.

Continue reading

Five weeks ago we began our month long journey through the world of bread with what Presbyterian scholar Choon-Leon Seow called the “remarkably mundane” story of food for the hungry, the feeding of the 5,000.

Five weeks ago we began our month long journey through the world of bread with what Presbyterian scholar Choon-Leon Seow called the “remarkably mundane” story of food for the hungry, the feeding of the 5,000. Most of the Bible texts from the Revised Common Lectionary this week present us with the well-worn and comfortable Biblical image of sheep and shepherds. Jeremiah rails against the shepherds of Israel “who destroy and scatter the sheep of [the Lord’s] pasture,”

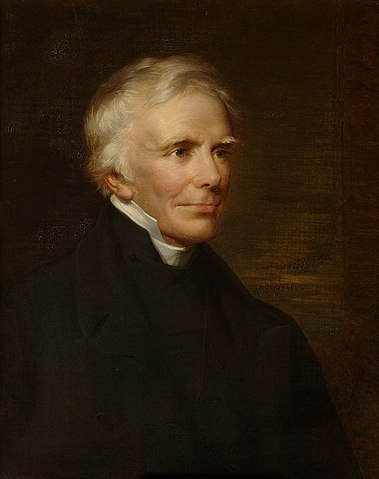

Most of the Bible texts from the Revised Common Lectionary this week present us with the well-worn and comfortable Biblical image of sheep and shepherds. Jeremiah rails against the shepherds of Israel “who destroy and scatter the sheep of [the Lord’s] pasture,” Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words:

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words: It had gone on so long she couldn’t remember a time that wasn’t like this. She lived in constant fear. She wasn’t just cranky and out-of-sorts; she was terrified. Her life wasn’t just messy and disordered; it was perilous, precarious, seriously even savagely so. It was physically and spiritually draining, like being whipped every day.

It had gone on so long she couldn’t remember a time that wasn’t like this. She lived in constant fear. She wasn’t just cranky and out-of-sorts; she was terrified. Her life wasn’t just messy and disordered; it was perilous, precarious, seriously even savagely so. It was physically and spiritually draining, like being whipped every day. For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.

For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.