You, who are on the road

must have a code

that you can live by.

And so become yourself

because the past is just a good bye.

Teach your children well . . . .

If you are as big a fan of the folk rock of the 1970s as I am, you will recognize the opening lines of Crosby, Still, Nash & Young’s 1970 hit Teach Your Children.[1] Graham Nash who wrote the song has said that it was inspired by a 1962 photograph take by Diane Arbus of a young boy in New York’s Central Park playing with a toy hand grenade. I have no reason to disbelieve that, but I wonder also if today’s lesson from the Book of Deuteronomy, Moses’ farewell address to the people he has led through Sinai to the brink of the Promised Land, might also have been in Nash’s mind. The song is a neat paraphrase of what Moses says.

You, who are on the road

Israel

must have a code

give heed to the statutes and ordinances that I am teaching you to observe . . .

that you can live by.

so that you may live to enter and occupy the land . . .

and so become yourself

for this will show your wisdom and discernment to the peoples, who . . . will say, “Surely this great nation is a wise and discerning people!”

because the past is just a goodbye

[do not] forget the things that your eyes have seen nor to let them slip from your mind all the days of your life . . .

teach your children well

make them known to your children and your children’s children.[2]

We are in the second day of what Americans like to call a “three-day weekend,” created by one of those national holidays adopted by Congress and scheduled not on a specific date but on a described Monday (in this case, the first Monday of September) so as to give working people three days rather than two away from their usual labors. In fact, we call this particular holiday “Labor Day” as a recognition that such times away from work are the result of the efforts of organized labor, the union movement of the early 20th Century.[3]

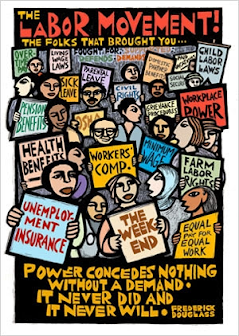

The Tompkins County Workers’ Center in Ithaca, New York, has created a poster listing all the things that Labor Day commemorates, all the things about living and working in our country that we take for granted but would not have if it were not for the efforts of organized unions. They include overtime pay, living wage laws, sick leave, parental leave, child labor laws, occupational safety and health regulations, employer-paid health care benefits, pension plans, workers’ compensation insurance, minimum wage laws, unemployment insurance, and even the weekend itself.[4]

These are, to us, what the statutes and ordinances taught to the Hebrews by Moses were to them. A code which defines us as a people, a people who believe in a fair wage for a fair day’s work, a people who believe that children should have a childhood rather than a dangerous job, and that they should have healthy parents with sufficient time away from work to spend with their children, time to play with their children, time to go to church with their children, time to teach their children well.

When I was in law school one of our first required courses was a one-semester seminar on the philosophy of law. In my seminar section we had a very lively conversation about whether one’s basic outlook should be what I would call an expansive approach to law or what might be called a restrictive approach. The former decrees that whatever is not expressly forbidden is allowed; the latter, that whatever is not expressly allowed is forbidden. As it turns out, the former is a constitutional principle of English and American law, while the latter is often relied on by German legal scholars.[5]

In today’s lesson from the Gospel of Mark, we encounter a debate between Jesus and the Pharisees about law and I think it boils down to the same debate we had in my first year law school seminar. The Pharisees take a restrictive approach to the Law of Moses; what is not expressly allowed is forbidden, and the letter of the law is to be rigidly followed. They take very seriously Moses’ admonition to “neither add anything to [it] nor take away anything from it, but keep the commandments” diligently.[6] We should remember that, although often cast as villains in some of the gospel stories, the Pharisees were not bad people. They were the committed religious people of the day, dedicated to keeping the Jewish faith alive, to ensuring its right practice, and to seeing that God was worshiped in what they felt was the proper way. It’s just that they were so keen on doing so, even to the point of specifying how to wash the dishes (“the washing of cups, pots, and bronze kettles” as Mark puts it[7]), that they failed to recognize when their teaching became burdensome to those who had less social, political, or economic power than they possessed.

Jesus, on the other hand, is an expansivist. For him whatever is not expressly forbidden is allowed, and to insist upon hard and fast rules and rigid application is to teach human precepts as doctrines, to “abandon the commandment of God and hold to human tradition.”[8] He warns his listeners and his followers that too much strict attention to the details of law can be as harmful as, maybe even more harmful than, too little. It is not, after all, these externals that are the issue. Whatever one’s practice, whichever traditions one does or does not follow, however one washes the dishes, these are not the things that get one ready for reign of God; it is rather what is internal, whatever is in one’s heart. “It is from within, from the human heart, that evil intentions come: fornication, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, wickedness, deceit, licentiousness, envy, slander, pride, folly. All these evil things come from within, and they defile a person.”[9]

In the first part of the Letter of James, just before the bit that is our epistle lesson this morning, the author echoes Jesus: “One is tempted by one’s own desire,” he writes, by what is in one’s own heart, “being lured and enticed by it; then, when that desire has conceived, it gives birth to sin, and that sin, when it is fully grown, gives birth to death. Do not be deceived, my beloved.”[10] And then comes what we heard this morning, the admonition to generosity of spirit, the instruction to “be doers of the word, and not merely hearers who deceive themselves,” the encouragement to true religion characterized by the care given those less fortunate than ourselves.[11] It is an expansivist understanding of the law; that which is not forbidden is allowed and, in fact in some cases, encouraged.

In the second verse of Graham Nash’s song, the tables are turned and children are encouraged to teach their parents: “Please help them with your youth,” runs the lyric, “they seek the truth before they can die.”

“Don’t you ever ask them why” both verses caution. Neither generation should probe too deeply into the dreams or fears of the other because “if they told you, you would cry. So just look at them and sigh . . . and know they love you.” The divide between good and evil runs down the middle of every human heart; if we delve too deeply into another’s heart we run the danger of encountering all those things there that Jesus warned about, all those “evil things [that] come from within, and . . . defile a person.” We should be content to know and accept the love that is offered for, after all, love is the law:

“‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”[12]

As the words of the second verse of Teach Your Children are sung, there is a countermelody also being sung. Its lyrics, often missed as we sing along with the more dominant melody, are these:

Can you hear and do you care and

can you see you must be free to

teach your children what you believe in and

make a world that we can live in?

This weekend we are privileged to enjoy an extra day away from our usual employments commemorating the fruits of organized labor, the family leave and health insurance and weekends off, the statutes and ordinances of American labor law that set us free to teach our children what we believe, to teach our children the things that define who we are, to make a world that we can live in, a world where love is the law, a world where truth is spoken from the heart, where there is no guile upon the tongue; where no one does evil to a friend, where no one heaps contempt upon a neighbor, where the wicked is rejected and those who fear the Lord are honored.[13]

Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost, September 2, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

The lessons used for the service are Deuteronomy 4:1-2,6-9; Psalm 15; James 1:17-27; and St. Mark 7:1-8,14-15,21-23. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Graham Nash, Teach Your Children (1970), sheet music available at Sheet Music Direct; also see this YouTube video

[2] Deuteronomy 4:1-2, 6-9

[3] U.S. Department of Labor, History of Labor Day, online

[4] Tomkins Counter Workers’ Center, online (The poster is the illustration heading the blog publication of this sermon.)

[5] See Wikipedia, Everything which is not forbidden is allowed, online

[6] Deuteronomy 4:2

[7] Mark 7:4

[8] Mark 7:7-8

[9] Mark 7:21-23

[10] James 1:14-16

[11] James 1:17-27

[12] Matthew 22:37-40

[12] Psalm 15:2-4

Well done, Son of the Living God. (Jesus tells us in John’s gospel that we are not servants but children of God).