Fifteen years ago when I came to Medina for the first time in my life to meet the people of St. Paul’s Parish and, with them, make the mutual determination whether our life-paths were to converge, Earl and Hildegarde picked Evie and me up at the Cleveland airport. They first took us to Yours Truly Restaurant where we had a bite of lunch and then they brought us here, so that we could see the church.

Fifteen years ago when I came to Medina for the first time in my life to meet the people of St. Paul’s Parish and, with them, make the mutual determination whether our life-paths were to converge, Earl and Hildegarde picked Evie and me up at the Cleveland airport. They first took us to Yours Truly Restaurant where we had a bite of lunch and then they brought us here, so that we could see the church.

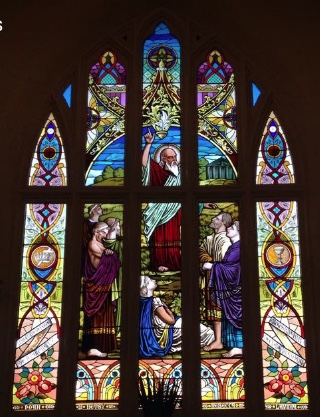

I walked into this worship space and, quite forgetting that the patron saint of the parish is Paul the Apostle, I looked up at the altar window and I thought, “Why do they have a stained-glass window of Socrates?” As some of you may know, there is a bust of Socrates by the Greek sculptor Lysippus in the Louvre museum in Paris that the man in that window looks a good deal like; I suspect the 19th Century artisan who made that window took it as his inspiration. Of course, it’s not Socrates in the window; it’s Paul holding forth amongst the philosophers of Athens at the Hill of Mars, a story told by Luke in the 17th chapter of the Book of Acts.

Nonetheless, I thought of Socrates and our window this week as I contemplated this Sunday’s lessons, two of which (the prophecy of Isaiah and the Letter of James) discuss the ministry of teaching and one of which tells the story of Jesus’ instructing the Twelve.

Last week we began our parish’s annual fund campaign with the theme “Transforming Generosity.” You should have received your pledge card for 2019 together with a letter about the nature of stewardship and generosity. There was an article in the newsletter similar to that letter, and early in the week you received an email (if you receive email) which is repeated on an insert in your bulletin this morning. Your parish leadership team has asked and will continue to encourage you to do two things that may seem contradictory: first, to make your financial commitment for 2019 earlier than usual, and second, to take your time in doing so. Our hope is that you will submit your estimates of giving on or before the first Sunday in November, but that you will give real prayerful and careful consideration to how your financial support of your church reflects your relationship with God. Stewardship, as that letter said, is not a matter of fund raising; stewardship is a matter of spiritual health. The “Transforming Generosity” theme hopes to inspire you to be a faithful steward and so to give as an expression of your relationship with God.

Last week we began our parish’s annual fund campaign with the theme “Transforming Generosity.” You should have received your pledge card for 2019 together with a letter about the nature of stewardship and generosity. There was an article in the newsletter similar to that letter, and early in the week you received an email (if you receive email) which is repeated on an insert in your bulletin this morning. Your parish leadership team has asked and will continue to encourage you to do two things that may seem contradictory: first, to make your financial commitment for 2019 earlier than usual, and second, to take your time in doing so. Our hope is that you will submit your estimates of giving on or before the first Sunday in November, but that you will give real prayerful and careful consideration to how your financial support of your church reflects your relationship with God. Stewardship, as that letter said, is not a matter of fund raising; stewardship is a matter of spiritual health. The “Transforming Generosity” theme hopes to inspire you to be a faithful steward and so to give as an expression of your relationship with God.

Five weeks ago we began our month long journey through the world of bread with what Presbyterian scholar Choon-Leon Seow called the “remarkably mundane” story of food for the hungry, the feeding of the 5,000.

Five weeks ago we began our month long journey through the world of bread with what Presbyterian scholar Choon-Leon Seow called the “remarkably mundane” story of food for the hungry, the feeding of the 5,000. Most of the Bible texts from the Revised Common Lectionary this week present us with the well-worn and comfortable Biblical image of sheep and shepherds. Jeremiah rails against the shepherds of Israel “who destroy and scatter the sheep of [the Lord’s] pasture,”

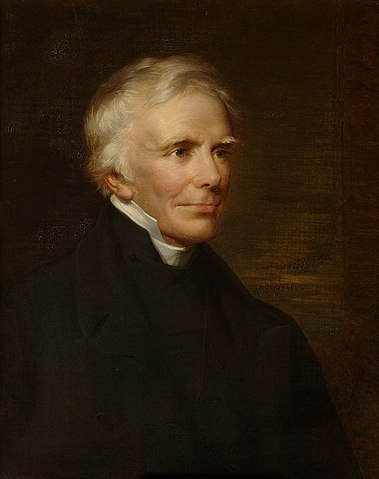

Most of the Bible texts from the Revised Common Lectionary this week present us with the well-worn and comfortable Biblical image of sheep and shepherds. Jeremiah rails against the shepherds of Israel “who destroy and scatter the sheep of [the Lord’s] pasture,” Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words:

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words: It had gone on so long she couldn’t remember a time that wasn’t like this. She lived in constant fear. She wasn’t just cranky and out-of-sorts; she was terrified. Her life wasn’t just messy and disordered; it was perilous, precarious, seriously even savagely so. It was physically and spiritually draining, like being whipped every day.

It had gone on so long she couldn’t remember a time that wasn’t like this. She lived in constant fear. She wasn’t just cranky and out-of-sorts; she was terrified. Her life wasn’t just messy and disordered; it was perilous, precarious, seriously even savagely so. It was physically and spiritually draining, like being whipped every day. For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.

For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods. What do you suppose it was like in Jerusalem on that Pentecost morning so long ago?

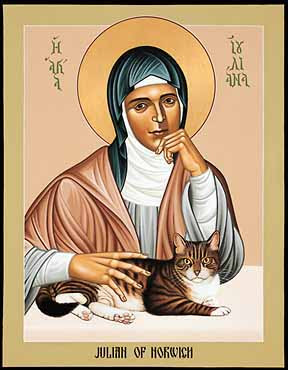

What do you suppose it was like in Jerusalem on that Pentecost morning so long ago? Today we are welcoming Reed C_____ F_____ into the Household of God through the Sacrament of Holy Baptism. We are also commemorating Dame Julian of Norwich, one of the medieval saints of English Christianity. Twenty-eight years ago I was ordained a deacon on Julian’s feast day which is actually on Tuesday, May 8. So the lessons we heard this morning, and the second of the two collect I offered after the Gloria in Excelsis, were from the propers for Dame Julian’s celebration. But I would like to read you also the brief Gospel lesson appointed for the Sixth Sunday of Easter, which is also from John’s Gospel

Today we are welcoming Reed C_____ F_____ into the Household of God through the Sacrament of Holy Baptism. We are also commemorating Dame Julian of Norwich, one of the medieval saints of English Christianity. Twenty-eight years ago I was ordained a deacon on Julian’s feast day which is actually on Tuesday, May 8. So the lessons we heard this morning, and the second of the two collect I offered after the Gloria in Excelsis, were from the propers for Dame Julian’s celebration. But I would like to read you also the brief Gospel lesson appointed for the Sixth Sunday of Easter, which is also from John’s Gospel