====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston at the funeral of James William McKee, July 28, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are from The Book of Common Prayer lectionary for burials: Isaiah 61:1-3; Psalm 23; Second Corinthians 4:16-5:9; and St. John 10:11-16. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

When I was practicing law and serving as the chief legal officer of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, there was a church member (of another congregation than mine) who always greeted me with a lawyer story. “What’s the difference between a lawyer and ….? ” “There was a lawyer who went to heaven ….” I think I’ve heard all the lawyer jokes, and I considered starting with one this morning. If I had had more than a passing acquaintance with Jim McKee, I might have done so. But I didn’t know Jim, so I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll begin with some poetry.

When I was practicing law and serving as the chief legal officer of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, there was a church member (of another congregation than mine) who always greeted me with a lawyer story. “What’s the difference between a lawyer and ….? ” “There was a lawyer who went to heaven ….” I think I’ve heard all the lawyer jokes, and I considered starting with one this morning. If I had had more than a passing acquaintance with Jim McKee, I might have done so. But I didn’t know Jim, so I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll begin with some poetry.

The death of anyone important in our lives is a tragic and painful thing. This is especially so when a father or grandfather passes away, perhaps because we use that metaphor of fatherhood to explain God’s relationship to us. Whenever a father or an older brother passes away, I cannot help but remember the poem by the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieve it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

As I said, I didn’t know Jim McKee; I do not know if he was Thomas’s wise man, a good man, a wild man, or a grave man, so I cannot eulogize him. But I do know that he was a father and I know that he was a lawyer specializing in what I think of as an esoteric specialty (intellectual property law), and that he had a loving wife, two children and five grandchildren, and that he loved football and golf (though he is said to have had no skill at the latter).

So I have a few things in common with Jim McKee. I’m also am a loving husband, a father, and a grandfather. I, too, am a lawyer (though my specialty, before I left active practice, was medical negligence litigation) and I am a terrible golfer.

I don’t play the game any longer, but as I was preparing to celebrate Jim’s life and preach this homily today, I got to thinking about golf. I remembered the observation made by someone (I can’t remember who) that there are probably more prayers said on the golf courses of America on Sunday morning than are said in its churches, although as evangelist Billy Graham once quipped, “The only time my prayers are never answered is on the golf course.”

I collect prayers, as you might suppose, and over the years I’ve collected quite a few golf-themed petitions. One of the nicer is this one:

God, What is my fascination with this game? Is it the outdoors – the green fairways, the blue skies, the lakes and trees, the feel of the breeze across my face? Is it the friends with whom I play – their companionship, their encouragement, the conversation between holes, the silence as we wait our turn? Is it the game – the balance between grace and skill and power, the striving for perfection, the loft of the ball, the precision of the putt? Or is it all of these, and in these, meditations about all of life – harmony, friendship, balance, and – every once in awhile – the perfect shot and a glorious Amen. (The Joy of Golfing)

I suspect that that prayer captures what it was about golf that attracted an intelligent and thoughtful man like James McKee.

Another golf prayer, one written by a man named Don Humm, begins this way:

Oh God, in the game of life, you know that most of us are duffers and that we all aspire to be champions with plenty of birdies or eagles.

Help us, we pray, to be grateful for the course including both the fairways and the rough. We thank you for those who have made it possible for us to tee off. Thank you for the thrill of a solid soaring drive; the challenge of the dogleg; the trial of the trap; the discipline of the water hazard; the beauty of a cloudless sky and the exquisite misery of rain and cold. (Presbyterian Church of the Roses)

The Buddhist writer Roy Klienwachter writes that “golf is a metaphor for life. It is up and down. The harder you try to win the worse you get. When you learn to let go the game gets easier. So,” he advises, “learn to play the game and go with it. The ‘practice’ is the game, learn to practice.” And Roman Catholic monk and golfer Thomas Moore writes that a game of golf is “an abbreviated, symbolic round of life. A green is like Eden: You reach it, and you feel that you have arrived at an unearthly place with its perfect grass and chance at salvation.”

In our lesson from the Gospel of John this morning, Jesus describes our salvation this way: “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep,” so that “there will be one flock, one shepherd.” (Jn 10:11,16) The Eucharistic prayer which we will offer in a few minutes picks up this theme of salvation, recalling that Jesus “stretched out his arms upon the cross, and offered himself, in obedience to [the Father’s] will, a perfect sacrifice for the whole world.” (BCP 1797, Pg 362)

Lutheran Pastor Chris Rosebrough uses golf as a metaphor to explain Christ’s atoning sacrifice:

Pretend you are a terrible golfer (for most there is not much imagination needed here). Now pretend that your eternal salvation depends on you scoring a perfect round of Golf (par or better for the entire round) at Bethpage Black (arguably the toughest golf course on the planet) and the course has been set up for U.S. Open conditions (7400 yards long, 8 inch rough and greens so fast it’s like putting in a bath tub). But, wait just to make things even more difficult, the devil has thrown in gail force winds that are swirling and gusting as high a 60 miles an hour.

To give you an idea of how difficult this feat is, Tiger Woods at the 2002 U.S. Open at Bethpage Black, with practically perfect weather conditions was the ONLY golfer with a score that was UNDER par. Phil Mickleson was the only other golfer that scored an even par for the tournament. Every other golfer was above par for the tournament. But under these course conditions not even Tiger Woods has any hope of being saved. Sadly, even if Jesus gave you a Mulligan then there would still be no hope of your being saved. One ‘do-over’ would be quickly gobbled up at Bethpage Black under these conditions.

So then how can you be ‘saved’ in this scenario?

The Gospel teaches us that even under these impossible conditions, Jesus Christ shot the perfect round of golf for you at Bethpage Black and is offering you His scorecard as your own. He’s already taken your scorecard, the one with all the sins on it, and he’s atoned for those sins on the cross. In return, He will give you His perfect scorecard and let you sign your name to it as if you were the one who shot that round. (Extreme Theology)

Our guaranteed salvation notwithstanding, we must still face those “impossible conditions” as we play the fairways and putt the greens of life even though we are assured that they cannot defeat us. As the rabbis teach, we must not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly now. Love mercy now. Walk humbly now. We are not obligated to complete the work but neither are we free to abandon it. We must, as the Buddhist philosopher said, continue to play the round and practice.

Thus, in Mr. Humm’s prayer, he give thanks that golf teaches us important life lessons: “how to get the right grip on life; to slow down in our back swing; to correct our crazy hooks and slices; to keep our head down in humility and to follow through in self-control . . . to be good sports who will accept the rub of the green, the penalty for being out-of-bounds, the reality of lost golf balls, the relevancy of par, the dangers of the 19th hole, and the authority of [the] rule book.” As Leonard Finkel wrote in Chicken Soup for the Golfers Soul, “In golf, as in life, obstacles are placed in our path. In overcoming these roadblocks, our greatest triumphs occur.” It is such times that we know that God (as Isaiah put it) brings good news to the brokenhearted, “the oil of gladness instead of mourning.” (Is 61:3)

New York Times writer Harold Segall observed that golf is “an adventure, a romance . . . a Shakespeare play in which disaster and comedy are intertwined.” The author L.R. Knost didn’t mention golf but she could certainly have been describing the game when she wrote:

Life is amazing. And then it’s awful. And then it’s amazing again. And in between the amazing and the awful, it’s ordinary and mundane and routine. Breathe in the amazing, hold on through the awful, and relax and exhale during the ordinary. That’s just living heartbreaking, soul-healing, amazing, awful ordinary life. And it’s breathtakingly beautiful.

As I said at the beginning, I did not have the privilege to know James William McKee. I do not know if he was the wise man, the good man, the wild man, or the grave man of Dylan Thomas’ poem. But I know from what I have been told that Jim did bless each of you with his fierce tears, that he battled bravely the cancer which finally took him from you, and that he did not go gentle into the night, but raged against the dying of the light. Nonetheless, his last putt has dropped into the cup; the light of his last day has faded into the darkness of death, and though his trophies may be few, his handicap still too high, and that hole-in-one still an unfulfilled dream, he is able to turn in that guaranteed perfect scorecard.

Today, we commend to almighty God the life and death of James William McKee – father, grandfather, lawyer, friend, lover of golf – whose life was, like a round of the game he loved, an adventure and a romance, amazing and awful and ordinary and routine and, like everyone’s in its own way, breathtakingly beautiful. Remember that, remember the beautiful part, and be assured that, through the grace of God, he is at rest in the final clubhouse, that building “not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.” (2 Cor 5:1)

I didn’t want to start this homily with a lawyer story but I’ll finish with one: A lawyer went to heaven. That’s it. No long tale, no punchline. Just a true story: A lawyer went to heaven. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

St. Paul’s Parish hosted the weekly “ice cream social” that accompanied the Community Band Concerts on Friday evening on the Town Square during summer. We’ve done this before although not for a few years (we tried for three years running to be host, but each Friday we were assigned during those years there was a thunderstorm and the event was rained out).

St. Paul’s Parish hosted the weekly “ice cream social” that accompanied the Community Band Concerts on Friday evening on the Town Square during summer. We’ve done this before although not for a few years (we tried for three years running to be host, but each Friday we were assigned during those years there was a thunderstorm and the event was rained out).  Sometime during the summer of 1969 (for the life of me, I can’t recall exactly when) and again in August of 1973, I was privileged to walk along the Promenade des Anglais on the Mediterranean waterfront of Nice. I was very young (or so I now consider myself to have been) and, on that second occasion, very much in love (or so I then considered myself) with a young French woman named Josienne. We quickly lost touch when that summer and my time as a student at the Sorbonne came to an end, but I have always fondly remembered her. Nice was her home town and, I suspect, is probably her home now. And I wonder, now, where she was on the evening of Bastille Day 2016. I pray she was not on the Promenade.

Sometime during the summer of 1969 (for the life of me, I can’t recall exactly when) and again in August of 1973, I was privileged to walk along the Promenade des Anglais on the Mediterranean waterfront of Nice. I was very young (or so I now consider myself to have been) and, on that second occasion, very much in love (or so I then considered myself) with a young French woman named Josienne. We quickly lost touch when that summer and my time as a student at the Sorbonne came to an end, but I have always fondly remembered her. Nice was her home town and, I suspect, is probably her home now. And I wonder, now, where she was on the evening of Bastille Day 2016. I pray she was not on the Promenade. Last Monday, we celebrated our country’s 240th birthday in a way that is quite different from other celebrations of what we might call “national identity days” around the world.

Last Monday, we celebrated our country’s 240th birthday in a way that is quite different from other celebrations of what we might call “national identity days” around the world.

As many of you know, this past week was a harrowing one for my wife and for me; specifically, Wednesday was one of those days you would rather not have to live through. In the afternoon, I was told by a urologist that I probably have prostate cancer, and later that night Evelyn nearly died from pulmonary embolism. She is OK now – I will be leaving right after this service to bring her home from the hospital – and my diagnosis will be either confirmed or proven wrong by a biopsy in about a month.

As many of you know, this past week was a harrowing one for my wife and for me; specifically, Wednesday was one of those days you would rather not have to live through. In the afternoon, I was told by a urologist that I probably have prostate cancer, and later that night Evelyn nearly died from pulmonary embolism. She is OK now – I will be leaving right after this service to bring her home from the hospital – and my diagnosis will be either confirmed or proven wrong by a biopsy in about a month.  The week of the summer solstice was an interesting one in the Funston household.

The week of the summer solstice was an interesting one in the Funston household.  Twenty-four years and 363 days ago I was made a priest; some what more than a year more than that, I have been a deacon. I have been in parish ministry for more than 26 years and on Tuesday I will celebrate the 25th anniversary of my ordination to the Sacred Prebyterate.

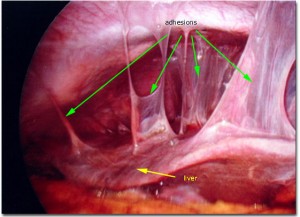

Twenty-four years and 363 days ago I was made a priest; some what more than a year more than that, I have been a deacon. I have been in parish ministry for more than 26 years and on Tuesday I will celebrate the 25th anniversary of my ordination to the Sacred Prebyterate. As a human body moves, its tissues or organs normally move and shift, repositioning themselves in relation to one another within a normative range; nothing in the body is static. These tissues and organs have slippery surfaces and natural lubricants to allow this. Inflammation, infection, surgery, or injury can cause bands of scar-like tissue to form between the surfaces of these organs and tissues, causing them to stick together and prevent this natural movement.

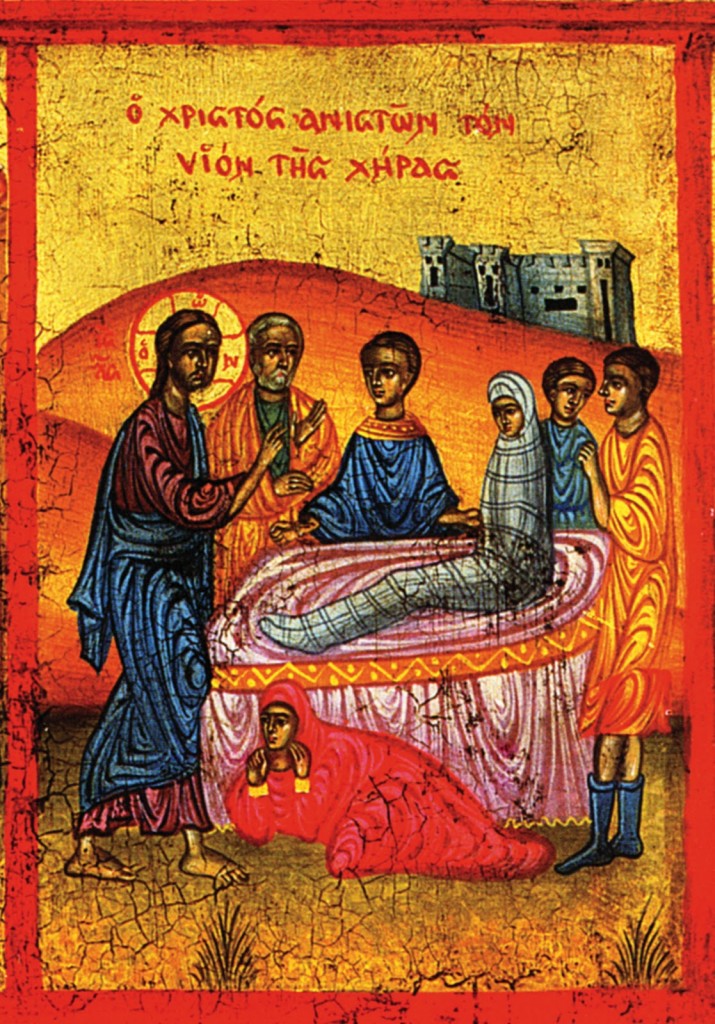

As a human body moves, its tissues or organs normally move and shift, repositioning themselves in relation to one another within a normative range; nothing in the body is static. These tissues and organs have slippery surfaces and natural lubricants to allow this. Inflammation, infection, surgery, or injury can cause bands of scar-like tissue to form between the surfaces of these organs and tissues, causing them to stick together and prevent this natural movement.  I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience.

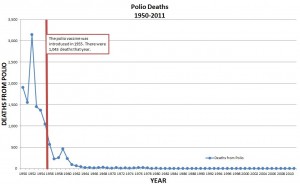

I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience. The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from

The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from  On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.

On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.