Today, by translation from Thursday, the 1st of November, we celebrate the Feast of All Saints.

Today, by translation from Thursday, the 1st of November, we celebrate the Feast of All Saints.

All my life as an Episcopalian (we didn’t have All Saints Day in the churches where I spent my childhood), I’ve been told that this day is about remembering all the saints who didn’t get a day of their own. Sure, we include Hildegarde and Francis and Richard Hooker and all those other folks with a feast day, but it’s really about those of whom the Book of Sirach says “there is no memory; they have perished as though they had never existed,” although they “also were godly [people], whose righteous deeds have not been forgotten.”[1] All Saints Day (and, thus, this Sunday) is a Christian festival celebrated in honor of all the saints, known and unknown, and frankly more in honor of the unknowns. It acknowledges the powerful spiritual bond between those in heaven (those we call the “Church triumphant”) and those of us still here on earth (we who make up the “Church militant”).

I’ve also been told, as I’m sure you have, that included in this commemoration are all the baptized who have ever lived and died. After all, the Catholic faith teaches that all faithful Christians are saints. St. Paul addressed his correspondence that way: for example, “To the saints who are in Ephesus…”[2] or “To the saints and faithful brothers and sisters in Christ in Colossae…”[3] So we are paying tribute to all departed baptized Christians.

Which is great, but then I am left wondering what November 2 is all about… If All Saints is about all those dead baptized Christians, what makes it different from the feast the next day that we call “All Souls” or the “Feast of All the Faithful Departed”? Why do we even have that day if that’s what All Saints Day is about. There must be something about All Saints that makes it different. According to one source, All Saints is about those dead who are believed to be already in heaven, while “All Souls was created to commemorate those who died baptized but without having confessed their sins, and thus they are believed to reside in purgatory.”[4]

Well, that’s fine for Roman Catholics, but we Anglicans (at least some of us) regard “the Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory [to be] a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.”[5] So . . . how do we non-Roman Catholics differentiate the Feast of All the Saints from the Feast of All the Faithful Departed?

I want to suggest to you today that difference is found in the fact that the Feast of All Saints is not only, and perhaps not even primarily, about commemoration of those who are dead and gone. Nor is it about some promised future when “the first things [will] have passed away.”[6] Since the Reformation, for those of us in the non-Roman Western church,

[T]he emphasis [of All Saints Day] is on the ongoing sanctification of the whole people of God. Rather than putting saints on pedestals as holy people set apart in glory, we give glory to God for the ordinary, holy lives of the believers in this and every age.[7]

The Feast of All Saints is about our present reality: the righteous who are in God’s hand[8] are you and me, the Church militant. So this celebration is about the people who gather here and in similar places on a regular basis, who hear the proclamation of the Gospel, pray for the good of the world, celebrate the Holy Mysteries, and then ask God to “send us into the world [with] strength and courage to love and [to] serve.”[9] On this day, the church pulls out all the stops, dresses the altar and the clergy in our finest white vestments, sets aside the regular Sunday lectionary, sings all the really great hymns, and celebrates us, the folks who strive every day to do our best to do “the work [God has] given us to do.”[10]

Part of that work is to “understand truth,”[11] to “not pledge [our]selves to falsehood, nor [swear] by what is a fraud,”[12] in the words of Psalm 24 appointed for today. Part of that work (it says in the Wisdom of Solomon) with that reliance on truth is to “govern nations and rule over peoples.”[13]

In earlier times and in earlier empires, not everyone in the church could participate in doing so. Emperors, kings, aristocrats, plutocrats, and oligarchs arrogated the task of governance to themselves, so members of the church not included in those “ruling classes” were urged to exercise their role in government by praying for the rulers. St. Paul wrote to the young bishop Timothy:

I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for everyone, for kings and all who are in high positions, so that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and dignity. This is right and is acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.[14]

Similarly, the Lord, speaking through the prophet Jeremiah, urged the Jews in Babylon to “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”[15]

Well, times have changed and the Church militant, the saints of God, the community of faith no longer lives in an empire or a kingdom or in exile in a foreign nation; the country in which we reside is not supposed to be a monarchy, a plutocracy, or an oligarchy. It is supposed to be a constitutional democracy, a democratic republic in which the right of every citizen, eighteen years of age or older, to vote is not to be denied or abridged by either the federal government or that of any state for reason of race, color, age, or sex.[16] We live in a time and in a country where the calling of the Church militant, of the living saints of God to govern and to rule the country in which we reside includes not only our prayers for our leaders, not only our work for the welfare of our land, but also our vote . . . and not merely our right and privilege to vote, but (I suggest) our duty to do so.

It is merely a happy coincidence that our Election Day falls on the Tuesday following All Saints Day. I’m told that a Tuesday was chosen by our 18th Century forebears because Wednesday was market day and November was chosen because it comes after the harvest was done, but before really bad weather sets in.[17] Whatever the reason, I believe it provident that we are, on this All Saints Sunday just before an important national election, reminded of our calling to understand truth, to eschew falsehood, and to govern and rule our country.

On All Saints Day itself one of the lessons for the Daily Office of Morning Prayer was from the apocryphal book of Second Esdras. In it, Ezra reports seeing a vision of heaven.

I, Ezra, saw on Mount Zion a great multitude that I could not number, and they all were praising the Lord with songs. In their midst was a young man of great stature, taller than any of the others, and on the head of each of them he placed a crown, but he was more exalted than they. And I was held spellbound. Then I asked an angel, “Who are these, my lord?” He answered and said to me, “These are they who have put off mortal clothing and have put on the immortal, and have confessed the name of God. Now they are being crowned, and receive palms.” Then I said to the angel, “Who is that young man who is placing crowns on them and putting palms in their hands?” He answered and said to me, “He is the Son of God, whom they confessed in the world.” So I began to praise those who had stood valiantly for the name of the Lord.[18]

I have to say that I rather prefer this vision to the similar one we find the Revelation of John of Patmos. There is something compelling about the Son of God being there with the saints, among the crowd, crowning them, and personally putting the palms in their hands, rather than enthroned on high and exalted like the Lamb in John’s vision.

This vision of Christ with the masses, yielding his glory and mixing in with his people, seems somehow quite in keeping with our celebration of all the saints, providing a model for saintly behavior. An early 20th Century Roman Catholic Lithuanian archbishop, George Matulaitis, once wrote:

May our model be Jesus Christ: not only working quietly in His home at Nazareth, not only Christ denying Himself, fasting forty days in the desert, not only Christ spending the night in prayer; but also Christ working, weeping, suffering; Christ among the crowds; Christ visiting the cities and villages.[19]

This is the Christ of Ezra’s vision; this is the Christ of the saints whom God calls and empowers for ministry, Christ visiting cities and villages energizing and authorizing his people for the ministry of governance.

An example of that authority is found in our gospel lesson today, the raising of Lazarus from the Gospel of John. At the end of the story, Lazarus comes from the tomb, “his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth.” Jesus says to the gathered crowd, “Unbind him, and let him go.”[20]

“Unbind him, and let him go!” These may be the most powerful words in the story, because with them Jesus not only frees Lazarus, he empowers the community of faith. Jesus has called Lazarus out of the tomb, but it is the task of the People of God to complete his revival. Lazarus is still wearing the clothing of death; it is the work of the saints to remove those burial shrouds and dress him for life.

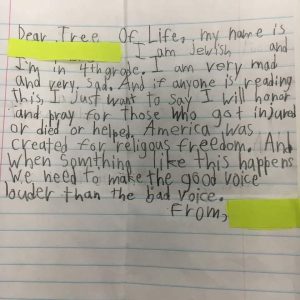

As we all know, our communities of faith have become battlegrounds, places where hatred invades and people die. We all remember the shooting at Mother Emmanuel Church; we all witnessed the shooting at Tree of Life Synagogue. Too many times in our country in our places of worship, our places of education, our places of employment, we have shrouded loved ones and dressed them for death. But in those horrific events and circumstances, the saints of God of all faiths have shined. The saints have reached out with prayer and comfort and support. In response to the Pittsburgh killings, a child from right here in Cleveland wrote these words to the Tree of Life congregation:

Dear Tree of Life, my name is __________. I am Jewish and I’m in 4th grade. I am very mad and very sad. And if anyone is reading this, I just want to say I will honor and pray for those who got injured or died or helped. America was created for religious freedom. And when somthing [sic] like this happens we need to make the good voice louder than the bad voice.[21]

The saints of God unbind others and set them free when, following our call to govern and exercising our franchise, we commit ourselves and our nation to making “the good voice louder than the bad voice.”

The saints of God unbind others and set them free when we vote for those who will alleviate, not exacerbate, the desperate plight of those who lack material means of survival, whether they are in our own communities, in places affected by natural disaster like Puerto Rico or the Gulf Coast, in distant lands ravaged by war, or from nearby countries coming to our borders seeking asylum.

The saints of God unbind others and set them free when we vote for those who would console a brother or sister crushed by loss or fear or despair, like those targeted by bombers or by gunmen in such places as Parkland High School or Mother Emmanuel Church or Tree of Life Synagogue.

The saints of God unbind others and set them free when we vote for those who would empower rather than intimidate and disenfranchise our fellow citizens.

This is the calling of the saints, of all the saints, whom we celebrate today, the righteous who are in the hand of God, the dead and the living, especially the living, the Church militant, you and me, called to govern the nation in which we reside in a manner that unbinds others and sets them free: we live up to that calling when we vote for those who are committed to truth and justice, to making “the good voice louder than the bad voice.”

Let us pray:

Almighty God, to whom we must account for all our powers and privileges: Guide the people of the United States and of this community in the election of officials and representatives; that, by faithful administration and wise laws, the rights of all may be protected and our nation be enabled to fulfill your purposes; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.[22]

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on All Saints Sunday, November 4, 2018, to the people of Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, Cleveland, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest preacher.

The lessons used for the service (All Saints, Year B) are Wisdom of Solomon 3:1-9; Psalm 24; Revelation 21:1-6a; and St. John 11:32-44. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Sirach 44:9-10

[2] Ephesians 1:1

[3] Colossians 1:1

[4] What’s the Difference Between All Saints Day and All Souls, Old Farmers Almanac, online

[5] “Article XXII: Of Purgatory,” The Articles of Religion, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 872

[6] Revelation 21:4

[7] All Saints’ Day, Presbyterian Mission, online

[8] Wisdom 3:1

[9] The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 365

[10] Ibid.

[11] Wisdom 3:9

[12] Psalm 24:4

[13] Wisdom 3:8

[14] 1 Timothy 2:1-4

[15] Jeremiah 29:7

[16] Amendments XV, XIX, and XXVI, U.S. Constitution

[17] Evan Andrews, Election 101: Why do we vote on a Tuesday in November?, History Channel, online

[18] 2 Esdras 2:42-47

[19] A Man of Remarkable Vision, Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception of the B.V.M., online

[20] John 11:44

[21] Note shared on Facebook

[22]“Prayer No. 24, For an Election,” Prayers & Thanksgivings, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 822

Leave a Reply