Our gradual this morning asks a question of God about human existence:

Our gradual this morning asks a question of God about human existence:

What is man that you should be mindful of him?

the son of man that you should seek him out?[1]

Whenever I read this psalm, my mind immediately skips to lines from William Shakespeare, to words spoken by the prince of Denmark in the play Hamlet:

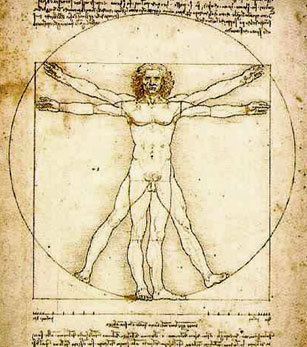

What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an Angel! In apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world! The paragon of animals![2]

I have always been certain that Shakespeare was riffing on Psalm 8.

The prayer book version of the Psalm uses the word “man” in the generic sense asking the question about all of humankind, then literally translates the Hebrew ben adam as “son of man” recalling to us a term Jesus often applied to himself. While that may make a certain amount of liturgical sense, it distorts the importance of the Psalm. As translated in the New Revised Version of scripture, Psalm 8 asks, “What are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?” This is a little closer to the initial meaning of the verse, but the original Hebrew is not pluralized. This translation loses the awe and wonder of a singular individual gazing up at the night sky and overwhelmed by the presence of divinity.

Rolf Jacobson, Professor of Old Testament at Luther Seminary, offers this translation:

What is a human being that you would remember him?

What is a mortal that you would care for her?

He notes that, “The use of the Hebrew particle mah (‘what’) rather than the expected particle mi (‘who?’) lends the question a derisive, disdainful edge. Rather than ask ‘who am I?’ the psalmist wonders, ‘What is this thing called a human?'”[3]

As I pondered this Psalm it seemed to me that that is the way we human beings tend to think of ourselves and one another, somewhat (or, perhaps, very) derisively and divisively, with considerable disdain. Sometimes, when we speak of another and unknowingly quote Hamlet, we do so in a very contemptuous tone of voice: “What a piece of work” we say. . . . and in the end that scorn was Hamlet’s attitude. He does not stop where I ended that quotation. Instead, he tells Guildenstern and Rosencrantz that “Man delights not me; no, nor Woman neither” declaring humankind to be nothing more than the “quintessence of dust.” As essayist and lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson wrote in the mid-18th Century, “We are, by our occupations, education and habits of life, divided almost into different species, which regard one another for the most part with scorn and malignity.”[4]

But the Psalm reminds us that that is not how God sees us.

You have made him but little lower than the angels;

you adorn him with glory and honor;

You give him mastery over the works of your hands;

you put all things under his feet . . . .[5]

God values the human beings so much that God calls on us to share in the creative work of responsible care for and protection of creation. God calls on us to join God in the work of ordering, shaping, stewarding, and caring for life on this planet. And we do this by praising God! “According to the theology of the psalm, human praise somehow makes God present as a protective reality for creation. Praise keeps out evil.”[6]

It is through our praises of God that we exercise what the Prayer Book version of the Psalm calls “mastery,” and what other translations call “dominion,” over

All sheep and oxen,

even the wild beasts of the field,

The birds of the air, the fish of the sea,

and whatsoever walks in the paths of the sea.[7]

The Hebrew verb here is a form of the word mashal. This is the same word used to describe the royal authority of Israel’s kings, an authority limited by the Law of Moses in the Book of Deuteronomy, an authority which must be exercised with equity, an authority which is not arbitrary, the authority of an equal or of a partner. The one given such authority must “neither exalt himself above other members of the community nor turn aside from the commandments.”[8] In giving us this authority over the works of God’s hands, God is trusting us to exercise stewardship not domination, protection not destruction, conservancy not consumption.

Verse 2 of this Psalm, as translated in the New Revised Standard Version, proclaims that “out of the mouths of babes and infants [God has] founded a bulwark . . . to silence the enemy.” The mumbled praise of babies, no less than the fully articulated worship of adults, raises a barricade against evil. “Not only professional temple singers but also little children participate in the duty and privilege of all humanity: In declaring God’s praise, babes and infants defeat the enemy and make real God’s orderly reign on earth.”[9] Praise of God is the beginning and end of our work; everything we do as stewards of creation must embody God’s praise.

We must be particularly mindful that our Lectionary gives us this Psalm in the context of lessons about marriage. First, the story of Adam and Eve, and then Jesus interpretation of that story when asked by the Pharisees about divorce. In the creation story of the second chapter of Genesis, all of the creatures over whom human beings are given the royal authority of stewardship are found to be inadequate as partners for the man, Adam; so God creates the woman, Eve, to be to Adam, as it says in our reading, “a helper as his partner.”[10]

Interestingly, this week the Daily Office Lectionary has had readings from the Prophet Hosea, the prophet who most clearly and forcefully used the marriage covenant as a metaphor for human kind’s relationship with God. The Genesis story and the story of Hosea and his long-suffering but constantly abiding and forgiving love for his adulterous wife Gomer remind us that our partnership with God in creation and, thus, our stewardship of all of God’s creatures is to be a relationship of deep love, enduring commitment, and real intimacy.

When Jesus answers the Pharisee’s question about divorce, he describes it as adultery, but he does not condemn it as unforgivable. Indeed, elsewhere in the Gospels, when invited to participate in the condemnation of a woman found guilty of adultery, he declines and convinces her accusers not to punish her.[11] For Jesus divorce is a cause for sadness, not for condemnation. Having answered the Pharisees’ question and soon thereafter explained his answer to the disciples, Jesus turns his attention to children, to the babes and infants out of whose praises God raises a barricade against evil, “for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs.”[12]

“Truly I tell you,” says Jesus, echoing Psalm 8’s call to humility, “whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.”[13] While the Psalm recognizes God’s gift to us of dominion, like Jesus with the child

. . . it also reminds us of our humility. We are each still that awestruck person gazing in wonderment at the stars. We bear the image of God; [but] we are not God. Our finitude and fallibility must be kept in mind as we exercise our responsibility. We are also reminded that we are a part of the creation over which God has granted us dominion. We do not stand apart from our fellow creatures, but we stand with them.[14]

For in the end, it is not only the praises of human beings, of mumbling babes and infants, of worshipping and prayer adults, but the praises of all creatures which raise that bulwark against the enemy, that barricade against evil. In words of Psalm 148:

Praise the Lord from the earth,

you sea-monsters and all deeps;

Fire and hail, snow and fog,

tempestuous wind, doing his will;

Mountains and all hills,

fruit trees and all cedars;

Wild beasts and all cattle,

creeping things and wingèd birds;

Kings of the earth and all peoples,

princes and all rulers of the world;

Young men and maidens,

old and young together.

Let them praise the Name of the Lord,

for his Name only is exalted,

his splendor is over earth and heaven.[15]

“What is a human being that you would remember him?” asks Psalm 8, “What is a mortal that you would care for her?” We are the stewards of the earth, the guardians of the praises of all of God’s creatures, the bulwark against evil. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost, October 7, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

The lessons used for the service are Genesis 2:18-24; Psalm 8; Hebrews 1:1-4;2:5-12; and St. Mark 10:2-16. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1]Psalm 8:5, BCP Version

[2] Act II, Scene 2

[3] Commentary on Psalm 8, Working Preacher, October 7, 2012, online

[4] The Rambler, No. 160, Saturday, Sept. 28, 1751, in Arthur Murphy, ed.,The Works of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., Volume I (Alexander V. Blake, New York:1842), page 246

[5] Psalm 8:6-7, BCP Version

[6] Paul K.-K. Cho, Commentary on Psalm 8, Working Preacher, June 11, 2017, online

[7] Psalm 8:8-9, BCP Version

[8] Deuteronomy 17:20

[9] Cho, op. cit.

[10] Genesis 2:20

[11] See John 8

[12] Mark 10:14

[13] Mark 10:15

[14] Elizabeth Webb, Commentary on Psalm 8, Working Preacher, June 15, 2014, online

[15] Psalm 148:7-13, BCP Version

Leave a Reply