A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

Then the Immigration and Customs Enforcement doubled down on Mr. Trump’s promises of “mass deportations” across the country, but especially in Southern California and particularly in Los Angeles (where I grew up, by the way). People took to the streets in protest; the administration used that as an excuse to nationalize the California National Guard and met the protesters not only with 2,000 guardsmen but with 700 Marines, as well.

When California’s senior senator tried to confront the Secretary of Homeland Security about this at a press conference, he was evicted, manhandled, wrestled to the ground, and handcuffed. And yesterday, hundreds of thousands if not millions of Americans took to the streets of more than 2000 cities and towns across this nation to express their opposition to the actions of Mr. Trump and his administration. Also yesterday, a Democratic politician in Minnesota and her husband were killed, and another was seriously wounded, in what the state’s governor described as clearly a “politically motivated assassination.”

Meanwhile, at an estimated cost of about $45 million, Mr. Trump held a Red Square style parade of military might through the streets of the capitol.

And, of course, Israel and Iran are lobbing missiles at one another.

In light of all of this, play and playfulness may no longer seem to be an appropriate topic for today’s homily, but it’s still Trinity Sunday, and the playfulness of God is prominently featured in the picture of Lady Wisdom in our reading from the eighth chapter of Proverbs. At the end of the lesson, she says:

[W]hen he [God] marked out the foundations of the earth,

then I was beside him, like a little child,

and I was daily his delight,

playing before him always,

playing in his inhabited world

and delighting in the human race.[1]

Wisdom, as described in this passage, is generally understood by Christians to be either equivalent to God’s Word or Logos, that is God the Son,[2] or a literary personification of God’s own wisdom.[3] In either event, her playfulness is clearly an attribute of God.

The Triune God, it has been said, is a “Friend who has Friends.” The relationships among the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, says Richard Buck, professor of ethics at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland, are like the “friendships of excellence” described by Aristotle in The Nicomachean Ethics. Such a friendship “is one in which each party endeavors to bring out the best in the other person; rather than seeking to get something out of the relationship individually. With both seeking the excellence of the other, both become better people.”[4]

Play, as theologian Brian Edgar says, is “a fundamental activity of those who are friends.”[5]

According to social psychologist Peter Gray, who studies tribal cultures and play, “[t]he golden rule of social play is not, Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Rather, it is, Do unto others as they would have you do unto them. The equality of play is not the equality of sameness, but the equality that comes from granting equal validity to the unique needs and wishes of every player.”[6] In the societies Gray has studied, the spirit of play, “in which people abide by rules willingly and freely, not because of threats imposed by more powerful others,” has “permitted them to avoid hierarchy, dominance, and coercion.” These cultures “are all marked by extraordinary egalitarianism and total commitment to cooperation and sharing.”[7]

By a not very remarkable coincidence, theologians tell us that this would would also characterize a human society modeled on the Holy Trinity. This is why I believe that the self-revelation of God as one-in-three and three-in-one that the Christian church proclaims really matters, and the doctrine of the Trinity is not just some esoteric subject for scholarly debate.

I think it matters because, despite the official separation of church and state in our secular democracy, religion has a profound influence on politics. Although it is not true that the United States is a “Christian country,” it is a fact that a majority of Americans self-identify as orthodox Christians of one denomination or another; according to the Pew Research Center, 62% of our population describe themselves as Christians.[8]

It is well-documented in sociological studies that the characteristics attributed to deities often reflect the values and social structures of the societies that worship them, and vice versa. The foundational characteristics of God appreciated as a Trinity are love, inclusivity, equality, and interdependence. The Trinity is not simply a doctrine to be understood; it “is not something that we perceive. It is the place where we dwell. The Trinity is our cosmic arch, the dwelling wherein we and everything else nestle.”[9]

Organizational Psychologist Ruth Wienclaw has found that

A person’s religious beliefs inform his or her worldview. This, in turn, affects how one acts in the world. It follows that a nation’s prevailing religious belief system affects its politics. This is true not only in countries that are openly theocratic in nature, but even in those that attempt to maintain the separation between the church or religion and the state.[10]

In proclaiming God as Trinity, the Church teaches a message of radical equality. “[I]n the orthodox view of the Trinity there is no hierarchy, no tiers of authority and power in the Trinity, and no gradations of glory and majesty. Nobody is lesser or greater than the other.”[11] “[T]he three persons of the Trinity are equal. … The Father is not more important than the Son, the Son is not more important than the Spirit – they are equal in importance and in their divinity.”[12]

God’s self-revelation as Trinity offers us a model of relationships characterized by mutual respect, service, and love. “By embracing the insights offered by the Trinity, [Christians] can work towards building communities that prioritize mutual support, collaboration, and the well-being of all their members, while still acknowledging and respecting our individuality and personal ambitions.”[13]

62% of Americans claim to believe in and follow this Triune God. As members of the Episcopal Church, we have all, I’m sure, repeated the promises of the Prayer Book’s baptismal covenant several times. We have promised to “proclaim by word and example the Good News of God in Christ” and to “strive for justice and peace among all people.”[14] This compels us to urge our brothers and sisters, that 62% of Americans, to embrace “an ethical vision founded on God’s trinitarian nature [which] obliges Christians to work towards a society modeled on communion: an egalitarian society of reciprocal sharing and love, rather than one based on individual autonomy, hierarchical relations, subordination, or profit.”[15]

South African theologian Johannes Deetiefs argues that

The doctrine of the Trinity, with its language of inclusiveness, equality and unity in diversity, … has the potential to foster inclusive communities where difference is not regarded as a threat, but rather welcomed and accepted. * * * The trinitarian grammar of personhood, of relationality, and of love is … conducive to a society where persons are considered as equals and are respected and welcomed rather than exploited or excluded.[16]

Ethicist Richard Buck says that the “lesson for humans [in the Trinity] is that we can be diverse individually and at the same time be completely intertwined with each other in a community.”[17]

American Catholic theologian Catherine Mowry LaCugna echoes Deetiefs and Buck, and adds particularity when she writes that Trinitarian faith repudiates “the racist theology of white superiority, the clerical theology of cultic privilege, the political theology of exploitation and economic injustice, and the patriarchal theology of male dominance and control.”[18] In a society modeled on the Trinity, says Professor Buck, the “focus would not be on individuality separated from all others, but would be on personhood defined by relationships with others in the community. Mutuality, not hierarchy, would be the rule. People would deal with one another as equals in terms of dignity and respect. There would be an openness to diversity and a desire to be inclusive.”[19] “[T]he Trinity, with its emphasis on inclusiveness and equality, advances democracy and political pluralism.”[20]

And that is why I believe the doctrine of the Trinity is relevant to our world, and why I don’t think play and playfulness are an inappropriate topic today. Lady Wisdom’s witness to the playfulness of God reminds us that “pleasure and playfulness are built into the very structure of things,”[21] and that when we play we imitate the Triune God and foster communities of inclusiveness, hospitality, diversity, generosity, and self-giving.

In a world where politicians are murdered, where troops are in the streets of our cities, and where nations are at war, we must never forget that. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Feast of the Holy Trinity, June 15, 2025 to the people of Harcourt Parish (Episccopal Church of the Holy Spirit), Gambier, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest presider and preacher.

The lessons for the service were Proverbs 8:1-4,22-31; Psalm 8; Romans 5:1-5; and St. John 16:12-15. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.

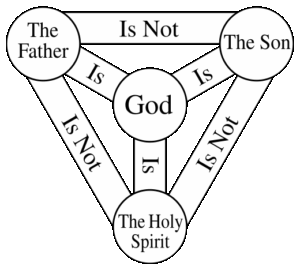

The illustration is the Scutum Fidei or Shield of Faith.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from Scripture are from the New Revised Version Updated Edition.

[1] Proverbs 8:29b-31 (NRSVue); I have changed “master worker” to “little child”, which I believe to be the better translation of the Hebrew amon.

[2] See, e.g., Anthony Selvaggio, Does Proverbs Speak of Jesus?, Reformation 21, July 1, 2008, accessed 14 June 2025

[3] See, e.g., In the Beginning With Lady Wisdom, The Bible Project, May 10, 2021, accessed 14 June 2025

[4] Richard Buck, Community and the Holy Trinity, The Furrow 71:3 (March 2020), pp. 156-59

[5] Brian Edgar, The God Who Plays: A Playful Approach to Theology and Spirituality (Cascade Books, Eugene, OR: 2017), preface

[6] Peter Gray, Hunter-Gatherers and Play, Scholarpedia 7(10):30365 (2012), accessed 10 June 2025

[7] Peter Gray, Play Makes Us Human II: Achieving Equality, Psychology Today, June 11, 2009, accessed 10 June 2025

[8] Religious Landscape Study, Pew Research Center, February 26, 2025, accessed 14 June 2025

[9] Terrance Klein, The Trinity reveals the foundation of the universe: Love, America Magazine, May 26, 2021, accessed 14 June 2025

[10] Ruth A. Wienclaw, Religion, Government and Politics, EBSCO Research Starters, 2021, accessed 12 June 2025

[11] Michael F. Bird, Trinity or Triarchy? Is There Authority & Submission in the Godhead?, Logos: Word by Word, April 3, 2023, accessed 9 June 2025

[12] Theo McCall, From the Chapel: The Trinity as Radical Equality, St. Peter’s College, 07 June 2024, accessed 10 June 2025

[13] Sam Sperling, Discovering the Trinity’s Relevance in Our Modern World: Confronting the Crisis of Individualism, Medium, September 29, 2023, accessed 12 June 2025

[14] The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 305

[15] Tim Redfern, Revisiting Trinitarian Social Ethics, Macrina Magazine, August 27, 2021, accessed 13 June 2025

[16]Johannes P. Deetlefs, Political implications of the Trinity: Two approaches, HTS Theological Studies 75:1, 23 May 2019, accessed 13 June 2025

[17] Buck, op. cit.

[18] Catherine Mowry LaCugna, God in Communion with Us: The Trinity in LaCugna (ed.) Freeing Theology: The Essentials of Theology in Feminist Perspective (Harper Collins, San Francisco:1993), p. 99

[19] Buck, op. cit.

[20] Deetiefs, op. cit.

[21] Terence E. Fretheim, God and the World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation (Abingdon, Nashville, TN: 2005), page 217

Leave a Reply