Fifteen years ago when I came to Medina for the first time in my life to meet the people of St. Paul’s Parish and, with them, make the mutual determination whether our life-paths were to converge, Earl and Hildegarde picked Evie and me up at the Cleveland airport. They first took us to Yours Truly Restaurant where we had a bite of lunch and then they brought us here, so that we could see the church.

Fifteen years ago when I came to Medina for the first time in my life to meet the people of St. Paul’s Parish and, with them, make the mutual determination whether our life-paths were to converge, Earl and Hildegarde picked Evie and me up at the Cleveland airport. They first took us to Yours Truly Restaurant where we had a bite of lunch and then they brought us here, so that we could see the church.

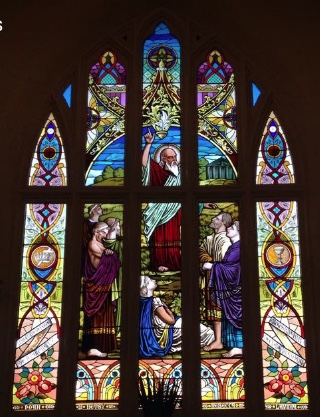

I walked into this worship space and, quite forgetting that the patron saint of the parish is Paul the Apostle, I looked up at the altar window and I thought, “Why do they have a stained-glass window of Socrates?” As some of you may know, there is a bust of Socrates by the Greek sculptor Lysippus in the Louvre museum in Paris that the man in that window looks a good deal like; I suspect the 19th Century artisan who made that window took it as his inspiration. Of course, it’s not Socrates in the window; it’s Paul holding forth amongst the philosophers of Athens at the Hill of Mars, a story told by Luke in the 17th chapter of the Book of Acts.

Nonetheless, I thought of Socrates and our window this week as I contemplated this Sunday’s lessons, two of which (the prophecy of Isaiah and the Letter of James) discuss the ministry of teaching and one of which tells the story of Jesus’ instructing the Twelve.

I will return to them in a moment, but first I want to make note of some contemporary American history. This weekend, yesterday to be exact, is the 55th anniversary of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in which four little girls were killed. The next day, Eugene Patterson, the editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, wrote and published an editorial which included these words:

A Negro mother wept in the street Sunday morning in front of a Baptist Church in Birmingham. In her hand she held a shoe, one shoe, from the foot of her dead child. We hold that shoe with her.

Every one of us in the white South holds that small shoe in his hand.

It is too late to blame the sick criminals who handled the dynamite. The FBI and the police can deal with that kind. The charge against them is simple. They killed four children.

Only we can trace the truth, Southerner – you and I. We broke those children’s bodies.

We watched the stage set without staying it. We listened to the prologue unbestirred. We saw the curtain opening with disinterest. We have heard the play.

We – who go on electing politicians who heat the kettles of hate.

We – who raise no hand to silence the mean and little men who have their nigger jokes.

We – who stand aside in imagined rectitude and let the mad dogs that run in every society slide their leashes from our hand, and spring.

We – the heirs of a proud South, who protest its worth and demand it recognition – we are the ones who have ducked the difficult, skirted the uncomfortable, caviled at the challenge, resented the necessary, rationalized the unacceptable, and created the day surely when these children would die.

* * *

Let us not lay the blame on some brutal fool who didn’t know any better.

We know better. We created the day. We bear the judgment.[1]

We can distance ourselves from that horrible bombing and from Mr. Patterson’s words geographically, after all we are in Ohio not Alabama or Georgia. We can distance ourselves from them in time, after all more than half a century has passed. We can distance ourselves culturally, after all we are Midwesterners not Southerners. At least, we can try to distance ourselves from them . . . but we know in our hearts that we cannot. It’s not just the South; it’s America. It’s not just fifty years ago; it’s now. It’s not them; it’s us.

We know in our hearts that James, the author of our epistle lesson this morning, is right. “The tongue is a fire!”[2] One small word can set off a conflagration; in today’s world one small “tweet,” one little Facebook post can do the same. One mention of a Unite-the-Right rally last year and thousands descended with their torches on Charlottesville, Virginia, and once again death was the result. The tongue, said James, is “a restless evil;”[3] it “sets on fire the cycle of nature, and is itself set on fire by hell.”[4] And so, James counsels, we must hold it in check and, interestingly, he advises us that we should not all aspire to the office or ministry of teacher.[5]

On the other hand, the author of the second part of the Book of Isaiah, boldly claims that mantel. In the third of the so-called “Servant Songs,” which Christians have traditionally understood as pre-figuring Christ, he sings, “The Lord God has given me the tongue of a teacher, that I may know how to sustain the weary with a word.”[6] Second Isaiah’s vision of the tongue is rather more redemptive than James’s, less dangerous, more comforting. And, yet, at the end of this Servant Song comfort has been displaced by contradiction: “Who will contend with me? Let us stand up together. Who are my adversaries? Let them confront me.”[7]

Here Second Isaiah seems to look back to and echo the sentiment expressed by the first Isaiah, the son of Amoz, at the beginning of this book of prophecy. “Come now, let us argue it out,” he wrote, speaking on behalf of the Lord.[8] The King James Version rendering of that invitation – ” Come now, and let us reason together” – was said to the favorite bible verse of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who became president because of another American tragedy not long after that church was bombed and those four little girls were killed.

Reasoning together was the preferred method of teaching adopted by Socrates; we have named this method after him, in fact. Conservative Christian author Kate Deddens describes this method as follows:

In the Socratic Method we see the birth of a basis and purpose of education that has as its ultimate goal the pursuit of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness – all attributes of God – through conversational dialogue: a process of questioning, answering, and further questioning. Socrates grasped the significance of reasoning through questioning . . . . Socrates modeled a method of instruction that was strikingly in accord with what we [find] in the Scriptures.[9]

Ms. Deddens is there specifically referring to the Lord’s invitation to his people to argue with him in First Isaiah, an invitation repeated in today’s reading from the third Servant Song in Isaiah 50, an invitation acted out by Jesus with his disciples in our gospel lesson.

“Who do people say that I am?”[10] he asks them as they walk along. They answer and then, in true Socratic (and frankly rabbinic) fashion, he follows up with another question, “But who do you say that I am?”[11] Peter answers, of course, with what we call his “confession” that Jesus is the Messiah. After ordering them to not yet share this others, Jesus begins to teach them what this means, probably making reference to Second Isaiah’s Servant Songs and their lessons of suffering such as we heard in today’s Old Testament reading. We can imagine that he might have continued to use the Socratic question-following-on-question method in doing so. As evangelical writer Brent Cunningham notes, Jesus frequently used this method, “push[ing] his listeners to come to grips with who he really was,” and encouraging his disciples “to develop deeper insight.”[12]

Indeed, as the gospel lesson ends, Jesus continues to teach by asking questions, “What will it profit them to gain the whole world and forfeit their life?”[13] “What can they give in return for their life?”[14] He reprimands Peter to set his mind on divine things and encourages all of his disciples and followers to not be ashamed.[15] In doing so, I believe he is encouraging an attitude best described as “generosity.”

Philosopher Levi Bryant, professor at Collin College in McKinney, Texas, has suggested that in all educational pursuits, such as a Socratic or rabbinic dialog or the reasoning together invited in the Book of Isaiah, there should be

. . . a principle of charity, of giving the most charitable interpretation to another person’s position (i.e., beginning from the premise that they’re rational beings and thus wouldn’t say things that are completely irrational, stupid, and bizarre such that if it seems like someone is saying such things you’re probably the one who’s misinterpreted, rather than the speaker being an irrational idiot).[16]

And, in addition to that, he says, there must be a principle of generosity, which he defines as “an openness to a plurality of theoretical lenses,” a willingness to see things from a variety of points of view.

Socrates, as I’m sure you know, was tried for “impiety” and for “corrupting youth” in Athens in 399 BCE; he was convicted by a majority vote of the 500 dikasts (or jurors) of the Athenian court. In accordance with the procedures of that court, he was asked to suggest a punishment other than the death penalty sought by his accusers. Some of his friends and disciples, including Plato from whose writings we know most about Socrates, urged him to be silent and to seek exile rather than death. His answer, as reported by Plato, was this:

Someone will say: Yes, Socrates, but cannot you hold your tongue, and then you may go into a foreign city, and no one will interfere with you? Now I have great difficulty in making you understand my answer to this. For if I tell you that to do as you say would be a disobedience to the God, and therefore that I cannot hold my tongue, you will not believe that I am serious; and if I say again that daily to discourse about virtue, and of those other things about which you hear me examining myself and others, is the greatest good of man, and that the unexamined life is not worth living, you are still less likely to believe me.[17]

We don’t actually have a stained-glass window dedicated to Socrates, but we might, we could. His teaching method and his admonition to virtue and to self-examination are fully in accord with our faith.

Our annual fund campaign for 2019 is encouraging us to consider the ways in which generosity can be transformative, to examine how our attitudes of generosity can be transformed and how practices of generosity can transform us. Perhaps if, with generosity, we were to follow Socrates’ advice and “daily discourse about virtue,” to examine ourselves and others, to consider the questions asked by Jesus of his first disciples and of us: “What would it profit us to gain the whole world and forfeit our life?” “What can we give in return for our life?” . . . .

Perhaps, if we were to do that, we might find that (in the words of today’s Gradual Psalm) God has already rescued our lives from death, our eyes from tears, and our feet from stumbling; we might discover that we always and every one of us walk in the presence of the Lord in the land of the living;[18] and we would learn that events such as happened 55 years ago in Birmingham, Alabama, or last year in Charlottesville, Virginia, events that seem to keep happening, truly need never happen again. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost, September 16, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

The lessons used for the service are Isaiah 50:4-9a; Psalm 116:1-8; James 3:1-12; and St. Mark 8:27-38. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Eugene Patterson, A Flower for the Graves, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 16, 1963, reprinted September 15, 2017, online

[2] James 3:6a

[3] James 3:8

[4] James 3:6c

[5] James 3:1

[6] Isaiah 50:4a

[7] Isaiah 50:8

[8] Isaiah 1:18

[9] Kate Deddens, The Power of Questions, Part I: Why the Socratic Method?, Classical Conversations, March 16, 2012, online

[10] Mark 8:27

[11] Mark 8:29

[12] Brent Cunningham, Jesus’ Use Of Haggada-Questions, Brent Cunningham Blog, March 4, 2008, online

[13] Mark 8:36

[14] Mark 8:37

[15] Mark 8:33,38

[16] Levi R. Bryant, Generosity, Larval Subjects Blog, October 6, 20ll, online

[17] Plato, Apology: In The Trial and Death of Socrates – Four Dialogues (Benjamin Jowett, tr., Dover Publications, Mineola, NY:1992), page 37

[18] Psalm 116:7-8

Leave a Reply