“Put things in order, … agree with one another, live in peace.”[1] That’s Paul’s advice to the Corinthians and to us this morning. It’s a goal to which we often pledge ourselves. Sometimes, though, the world makes it hard to get there.

“Put things in order, … agree with one another, live in peace.”[1] That’s Paul’s advice to the Corinthians and to us this morning. It’s a goal to which we often pledge ourselves. Sometimes, though, the world makes it hard to get there.

In January of 2013, a 16-year-old girl in Detroit, Michigan, was minding her own business in a public playground when she became the innocent victim of a drive-by shooting. Two years later, on June 3, 2015, on what would have been her 18th birthday, her friends decided to honor her memory by dressing in her favorite color, orange, which just happens to be the color hunters wear for safety. The next year, they decided to do it again and create a campaign for gun violence awareness. Thus was born Wear Orange Day which has since become Wear Orange Weekend.[2] Also in 2016, some of us Episcopal clergy here in Ohio heard of their effort and decided to join it by making and wearing orange stoles on the first Sunday of June.[3]

That is why I’m not wearing a white stole this morning although that would be the normal thing to do on this, the feast of the Holy and Undivided Trinity.

Some clergy like to say that this is the only feast of the Christian liturgical year on which we celebrate a doctrine, but that’s not really true. We celebrate the doctrine of the Incarnation at Christmas. We focus on the doctrine of Atonement, by whatever theory we may try to understand it, on Good Friday. We revel in the doctrine of Salvation at Easter and get caught up in the doctrine of Inspiration on the Feast of Pentecost. On each of these holy days we celebrate doctrines as they illuminate and help us understand aspects of our faith and our life together as a church and individually as members of it. Today, we celebrate the doctrine of the Trinity as it illuminates and helps us to understand our life in community, for that is what the Trinity is: a community of three Persons united in one Godhead.

So I’d like to begin our exploration of community with a question: Do you know the name Frigyes Karinthy?[4] Unless you’re a student of obscure fantasist literature, probably not, but I’m willing to bet you know a little something of his work. Karinthy was a Hungarian author in the first half of the 20th Century, perhaps best known in English for two novellas continuing the adventures of Jonathan Swift’s character Lemuel Gulliver. He is more widely, if anonymously, known however for the idea underlying his 1929 short story “Chains” – the intuitive notion that every person has some indirect connection through a small set of intermediaries to every other person in the world. In the story, a group of people play a game trying to connect any person in the world to themselves by a chain of five others, or in the terms we’ve come to know it best, by “six degrees of separation.”

In social psychology, this idea has been labeled the “small world theory.”[5] It has been tested a number of times, perhaps most famously by researcher Stanley Milgram in two studies in the 1960s, one sponsored by the popular magazine “Psychology Today” and a more rigorous undertaking under the auspices of the journal “Sociometry.” Milgram’s study results showed that people in the United States seemed to be connected by approximately three friendship links. Since then, more recent studies using internet data have suggested that globally we human beings are connected by an average of about 4-1/2 friendship links.[6] Since I don’t know how one can have half a friendship, let’s round that up to five and – voila! – our Hungarian fantasist Frigyes Karinthy turns out to have been correct.

We’re all connected through short chains of acquaintance. We are all in one world-wide community and it is, as the social theory’s name suggests, a small world. So let’s return to our Christian model of the perfect community, the Holy and Undivided Trinity.

To say that God is both Three and One is, of course, paradoxical. This doctrine by which we seek to understand God is a mystery, an aspect of our faith that we cannot totally comprehend. As finite beings we cannot comprehend an infinite God. However, we can apprehend the Trinity, which is to say that we are conscious of it, aware of it but fail to fully grasp its meaning so as to be able to pass any judgment about it; we know that it is but we cannot affirm or deny anything about it.[7] “While we can speak of God… , we must also remember that silence is the best description of the One who is beyond all.”[8]

One of my favorite internet memes is that picture of actor Sean Bean as the character Boromir from “Lord of the Rings” with the caption “One does not simply say ‘The Trinity is like….’” It truly underscores the problem of analogies, metaphors, and similes preachers have used to try and wrap our heads around the nature of God. You’ve heard plenty of them, I’m sure: St. Patrick’s famous use of the three-lobed shamrock;[9] St. Augustine’s psychological analogy to “the mind, and the knowledge by which it knows itself, and the love by which it loves itself;”[10] the somewhat pedestrian metaphor of water, ice, and steam;[11] the Scutum Fidei or “shield of faith,” that triangular diagram which has been around since the 12th Century or earlier;[12] and so on.

The issue with all metaphors and analogies is that they are limited. On the one hand, to say that one thing is “like” another is very different from saying that the one thing is the other thing. When we make that shift from simile to identity with respect to God we leap straight into heresy. One the other hand, to put too many qualifications on an analogy renders it nearly useless. The great novelist and Christian humanist Dorothy Sayers once wrote in answer to the question “What is the doctrine of the Trinity?”:

“The Father incomprehensible, the Son incomprehensible, and the whole thing incomprehensible. Something put in by theologians to make it more difficult – nothing to do with daily life or ethics.”[13]

Our God metaphors – and I remind you that all God-talk is metaphorical – walk a fine line between heresy and incomprehensible gibberish, but I disagree with Ms. Sayers about the Trinity. I believe this model of perfect community has a lot to do with daily life and ethics.

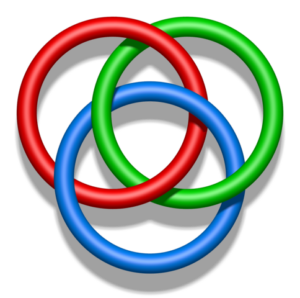

Having said all that about the dangers and possible uselessness of analogies, I now want to draw your attention to one that I think works: it’s the visual metaphor called “the Borromean rings.”[14] You’ve seen these, I’m sure. Most commonly depicted as three circles in a triangular formation reminiscent of Celtic knotwork. The three rings are interwoven so that they cannot be pulled apart although no two rings are linked together. In other words, no individual circle links with any one other, but the figure is an interwoven whole which cannot be disentangled. Like the three circles of the Borromean rings, each member of the Trinity is separate and distinct; thus, we refer to each as a Person – Father, Son, Holy Spirit. But also like the Borromean rings as a singular formation, the members of the Trinity share one nature and are inseparable.

This is what makes many attempts to rename the Persons of the Trinity in gender-neutral or gender-inclusive ways dangerously incomplete and misleading. To illustrate, you may have heard the formula “Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer,”[15] which initially seems not objectionable but on further reflection reduces the Persons to functions and inaccurately suggests that creation is the province of only the Father, salvation the business of only the Son, inspiration and comfort the action of only the Spirit, but this is not our understanding of the Trinity. The three Persons of God cannot be reduced to divine functions.

With regard to creation, for example, we confess in the Creed that it is through the Son that “all things are made”[16] and that the Spirit, whom Scripture describes as moving across the waters of creation,[17] is “the giver of life.”[18] In every instance of creation, and also every moment of redemption, every occasion of inspiration or sustenance, all three Persons are active participants. In the Trinity there is unity of purpose, a perfect fusion of personal activity: the three Persons think, decide and act together, with all divine acts flowing down the singular channel of the divine nature. In the truest sense of the word, the three Persons of the Trinity co-operate, perfectly. And what this divine community does perfectly, we mirror imperfectly.

We are, as Genesis says, “created in the image of God.”[19] As God is within the community of the Trinity, so we are made to be. Humans are made to live in community and to have meaningful, loving relationships with other humans; we are made to need community.[20] Those short chains of relationship intuited by Frigyes Karinthy and experimentally verified by Stanley Milgram and other researchers reflect this. The small world hypothesis testifies to the image of the Trinity mirrored, however imperfectly, within human society. Like the distinct but interwoven and inextricably bound Persons of the Trinity within Whom “we live and move and have our being,”[21] we live individual but interwoven and inextricably connected lives.

There are not “six degrees of separation” between human beings; there at most six degrees of connection amongst us, often fewer as research shows. No matter how large this world may seem, no matter how distant the events we see on our cable news shows or read about in our newspapers, it turns out that Walt Disney was right: It’s a small world after all. In truth we live and move and have our being in a small-world community mirroring the Holy and Undivided Trinity.

This means that although we here are more than 200 miles from Detroit and distanced in time by more than a decade, we are linked in a small, Trinity-reflecting community to Hediya Pendleton and are wounded by her death; we are linked in a small, Trinity-reflecting community to her killer and share responsibility for his actions. And we are similarly linked and bound to, wounded with, and responsible for the lives lost and injured in that school in Uvalde, Texas; that grocery store in Buffalo, New York, that church in Charleston, South Carolina; that synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and all the other places we can name and many others we don’t even know.

“Put things in order, … agree with one another, live in peace.” On this Wear Orange, Gun Violence Awareness Sunday, this Feast of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, let us once again pledge ourselves to that goal. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on Trinity Sunday (the First Sunday after Pentecost), June 4, 2023, to the people of Church of the Holy Spirit, Harcourt Paris, Gambier, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was supply clergy.

The lessons for the day are from the Revised Common Lectionary: Genesis 1:1-2:4a; Psalm 8; 2 Corinthians 13:11-13; and St. Matthew 28:16-20. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.

Illustration of Borromean rings from Wikipedia Commons, made by Jim Belk, Public Domain.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] 2 Corinthians 13:11 (NRSV)

[2] About Wear Orange, Wear Orange website, accessed June 1, 2023

[3] Emily McFarlan Miller, Episcopal clergy go orange against gun violence, Religion News Service, May 27, 2016, accessed June 1, 2023

[4] Frigyes Karinthy, Wikipedia, accessed June 1, 2023

[5] Gardiner Morse, The Science Behind Six Degrees, Harvard Business Review, February 2003, accessed June 1, 2023

[6] Six Degrees of Separation, Wikipedia, accessed June 1, 2023

[7] Bob Martin III, 14 Essential Doctrines of Christianity, Binmin website, accessed June 1, 2023

[8] Justin Coutts, A Celtic View of the Trinity, In Search of a New Eden, November 21, 2021, accessed June 1, 2023

[9] Justin Deeter, 4 Bad Analogies for the Trinity, Justin Deeter website, January 24, 2014, accessed June 1, 2023

[10] Augustine of Hippo, On the Trinity: Books 8-15, Stephen McKenna, tr., Cambridge:2002, page 171

[11] Deeter, op. cit.

[12] Dani Rhys, Shield of the Trinity – How It Originated and What It Signifies, Symbolsage, accessed June 1, 2023

[13] Dorothy L. Sayers, Strong Meat, 1939, accessed June 1, 2023

[14] Evelyn Lamb, A Few of My Favorite Spaces: Borromean Rings, Scientific American, September 30, 2016, accessed June 1, 2023

[15] See, for example, the opening invocation of this liturgy from the Church of England, accessed June 1, 2023

[16] “The Nicene Creed,” Holy Eucharist Rite II, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 358

[17] Genesis 1:2

[18] “The Nicene Creed,” op. cit.

[19] Genesis 1:26-27

[20] Mark Ballenger, What Does the Trinity Teach Us About Relationships?, Apply God’s Word website, accessed June 1, 2023

[21] Acts 17:28 (NRSV)

Leave a Reply